Concordia Fine Arts Class Draws on the Neurosciences

Convergence Initiative Unites the Arts and the Sciences

The concepts of stimulation and inhibition are interdisciplinary.

What inspires you? What motivates you? What holds you back? What brings you down? These questions must be addressed, no matter what it is that you’re trying to produce. Stimulation and inhibition are the building blocks for creation.

Divergences, however, exist in the ways stimulation and inhibition are approached.

Dr. Cristian Zaelzer, founder and director of the Convergence, Perceptions of Neuroscience Initiative—a joint effort between McGill University’s Brain Repair and Integrative Neuroscience Program and the Faculty of Fine Arts of Concordia University—explained that these differences are what need to be addressed in order to build a “strong, more educated society.”

Zaelzer spoke at a public lecture on Nov. 25 entitled “The Black Box,” held in the Montreal General Hospital’s Livingston Lounge. He explained that the arts and sciences share the same goal: exploring the nature of things. Over time, he said, the two fields arrived at a fork in the road and have grown further and further apart ever since. Now, it is time to “try to reconcile the disciplines.”

A new Concordia Fine Arts course, DART 461, will do just that. The independent study, which will take on the name of the initiative, will become Concordia’s official contribution.

Dr. pk langshaw, chair of Concordia’s Design and Computation Arts program, will teach the course. It will follow a similar structure to what participating students saw last Friday, explained Kimberly Glassman, the Fine Arts Communication Manager. She explained that the 20-odd Fine Arts students will attend monthly lectures and private tours, alternating between focusing on the use of art in the sciences and vice versa.

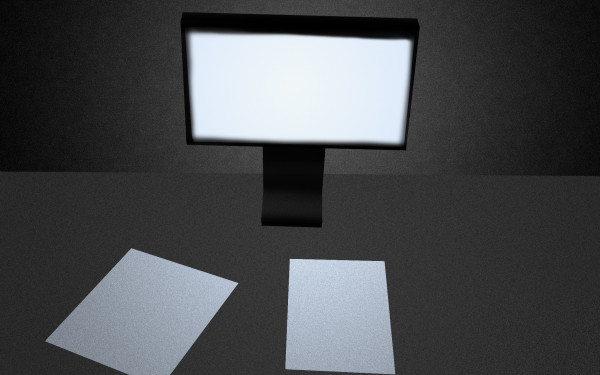

Prior to the evening’s neuroscience lecture, the art students were given a private tour of some of the MUHC’s neuroscience laboratories. On Dec. 11, they will be flipping the script by bringing the scientists out of their elements, into an exhibition called “The White Box.”

“It’s the other side to ‘The Black Box,’ where we explore the exhibition space. Just like today where we brought artists out of their comfort zone and brought them into the labs,” said Glassman. “We’re getting a guided tour of the Musée d’art contemporain, the SBC Gallery of Contemporary Art, and the Visual Voice Gallery, which is actually an art-science lab and gallery.”

The one-hour talk, a condensed and distilled introduction to neuroscience presented by PhD candidates Sejal Davla and Marie Franquin, gave the students a simplified road map to the brain. One step at a time, Davla and Franquin dove into the way in which the brain processes information, which Davla said can be considered its main function. From the molecular transmission of stimulants and inhibitors to the networking of neurons, the students were left with a lot to consider.

“It’s a huge amount of information to receive in three or four hours,” explained Eryn Tempest, a Concordia contemporary dance student. “It’s a lot of words and terminology that’s not in our currency, so it makes my brain work very fast.”

“We’re definitely learning,” agreed Caroline Laurin-Beaucage, a part-time faculty member in the Department of Contemporary Dance. “It’s also guiding us to view our field in a different way. How can we relate to that? The science is so specific and what we’re working on is so specific, also. The question of how do we bridge, from one to the other, is a part of the class.”

Glassman explained that the class will culminate with the Canadian Association of Neuroscience’s annual meeting at the end of May. The Convergence students will curate an exhibition of works produced throughout the class, while volunteers such as Glassman and other undergraduate art history students will prepare a catalogue to run alongside it.

While the topics, which will be covered throughout the program, will stray far from an artist’s comfort zone, Tempest said finding something meaningful, through all the science-specific jargon, isn’t too much of a stretch. “I think if you’re looking to glean meaning for you, to attach the information to something that’s relevant for you, then it’s not a question of needing to remember all the facts.”

She explained that, of all the information she gathered throughout the day, what resonated the most wasn’t necessarily the important material in regards to neuroscience. Rather, Tempest continued, it’s the material, even if just mentioned in passing, which is the most interesting.

“It’s good when information brings you to a place where you’re asking different questions,” she said. “In fact, it’s probably more interesting than when it brings you up to a place that’s like ‘Oh yeah, that’s the answer.’”

2web_900_454_90.jpg)

web_900_507_90.jpg)