The sculpted human form across history

Examining how bodies have been sculpted throughout time

The word statue might evoke images of larger-than-life, white marble figures in regal philosopher poses, like the ancient Greek statues that go hand-in-hand with the European idea of fine arts.

Thankfully, that's not all there is. It's time to look past the Apollos and Aphrodites by looking at some of the different ways people have sculpted the human form across history. It's time to pull back the curtain behind the Eurocentric lie that is fine arts.

The European idea of fine art comes from the Greco-Roman classical era. This tendency to put the past on a pedestal came into force during the Italian Renaissance with the Humanist movement.

“Humanists were also very interested in eloquence, which was an area of study that was promoted in the classical world. Humanists tried to rehabilitate it in the Renaissance world,” explained Steven Stowell, an art history professor at Concordia. “Sculpting the human body was often the highest test of an artist, [...] the ultimate test of an artist to be able to [sculpt the human body].”

That helps to explain the importance placed upon statues like Michelangelo's David and other white marble Renaissance statues.

“[Renaissance sculptors] saw the body as an expression of God's craftwork, or God's artistry. Its beauty reflected the divinity of God,” Stowell said. “It was part of God's creation, but also, since they saw humans as the highest of God’s creations, it was one of if not the most beautiful thing God created.”

The curator of the pre-Columbian section of the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, Erell Hubert, highlighted that sculptors in the region of what is now Peru heavily detailed the parts of statues that were necessary to identify the person and seemed to almost ignore the parts that weren't.

There's an earthenware statue titled Standing Female Figure in the Mesoamerican section of the gallery; the head and face are the most detailed aspects of the sculpture. The statue features an enlarged, deformed skull. According to Hubert, this procedure of deforming the skull to achieve an altered shape was painless and performed on infants. It was a widely recognized status symbol.

She explained how extra attention was given because the face represents a person; looking at a person's face is how we identify and communicate with each other. The statue has no prominent genitalia. According to Hubert, the slit is just enough to denote the subject as female. The figure similarly lacks arms or detailed legs, because these periphery features are not needed to understand the figure.

This statue features only what is needed to identify it: a warped skull to denote status, a detailed face to show its humanity, a shadow of a genital for its sex, and nothing more. “[It was] quite common in the Andes, and other places in the world, [art] style attempts to represent humanity with minimal distinct figures,” Hubert concluded.

Along with minimalistic aesthetics, some statues offer functionality along with their beauty. In the African section of the gallery, there are some Songye power figures. The crown of the head, and the head itself, were traditionally important to the Songye, but Hubert explained that the most important part of the body was the navel, where the umbilical cord is cut. She explained how the Songye created a hollow space in the statue, accessed through the navel. Substances placed inside imbued the statue with magical powers, according to Songye tradition. The statues are both a representation of humans, and a ritual item designed to affect the material world.

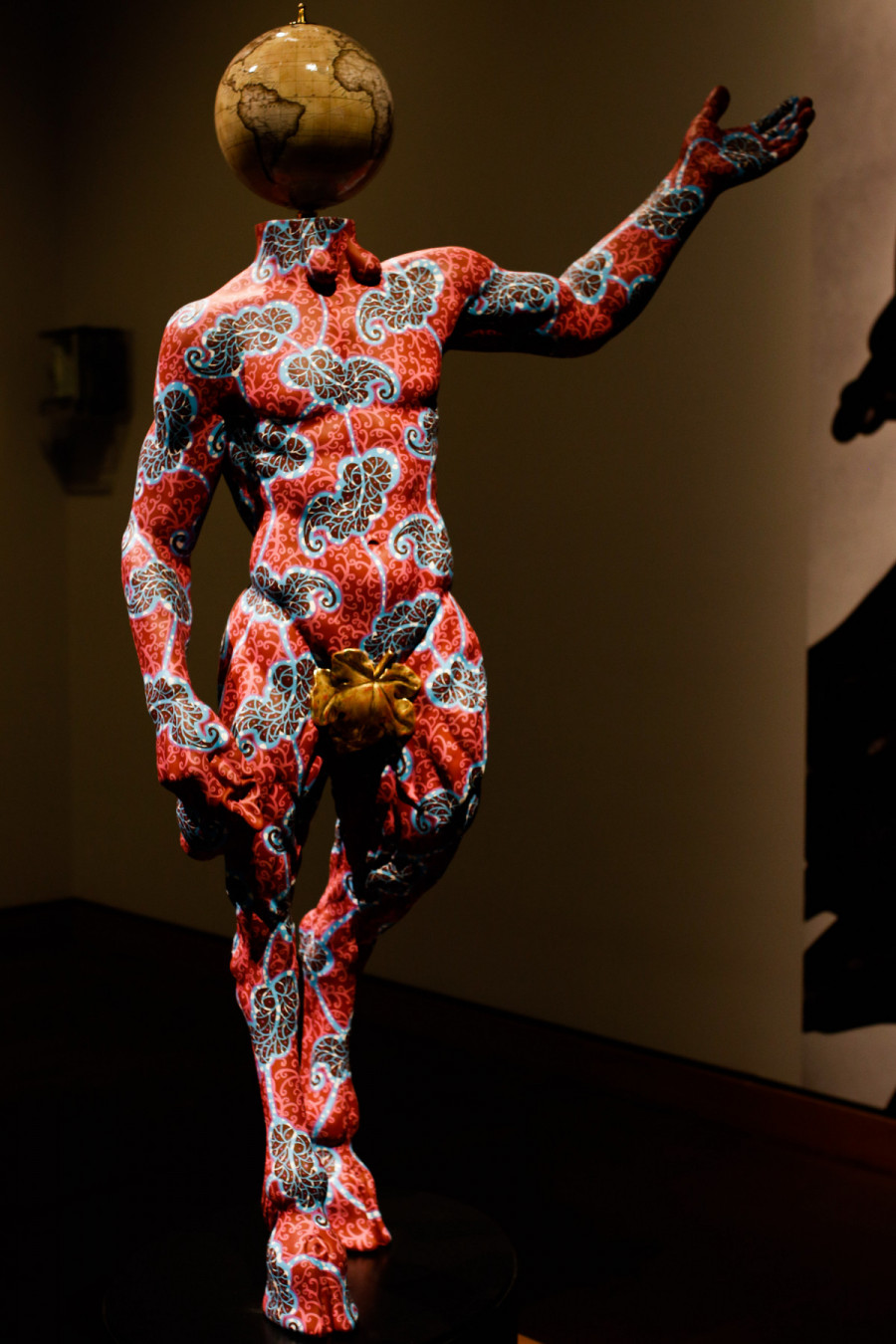

Yinka Shonibare's Pan directly challenges the Greco-Roman classical ideal through a post-colonial lens. This statue is a thoughtful reflection on the ideals of classical art, located near the exit of the Art of One World gallery in the MMFA.

Within the last century, contemporary sculpting has seen a major shift in subject matter. “I do think that sculptrors were influenced by the feminist movement using women models, older women for example, or women who did not have [conventionally] beautiful bodies.” said Nancy Skreko Martin, an American sculptor. Skreko Martin can speak both as a student of art and as an artist in the field since she holds a master’s degree from Bradley University and has had her work featured in the Smithsonian museum.

“I think the trend in contemporary sculpture, particularly in monuments, is [moving] away from figurative work,” said Skreko Martin. “One of the things I see more artists doing is [fragmenting] the image. In other words, I see more sculptures that are just a leg, or a pair of legs, or an arm.” She hypothesized that this trend in sculpting is due to the invention of computer assisted design programs and the commonality of smart phones with the potential to take high definition photos.

Perhaps figure sculpting for accuracy is fading away, but Skreko Martin has said that artists are still creating figures, as Shonibare's Pan attests. The MMFA gallery has both feminine subjects in their galleries and sculpted figures in their Art of One World gallery. The human body has taken on many forms across humanity's history, illustrating that there is no singular correct way to see and value human shapes or forms.

This article originally appeared in The Body Issue, published February 1, 2022.