Are Virgins Better People?

Jessica Valenti Talks Myths, Virginity and Online Feminism

Jessica Valenti doesn’t believe that a woman’s moral compass is located in between her legs.

She points out though, that if you look at the mainstream media’s depiction of a sexy—but not sexual—virgin, or subscribe to popular conservative rhetoric, then you might have heard otherwise.

“Women are more than the sum of our sexual parts,” she says, in a documentary based on her book The Purity Myth: How America’s Obsession with Virginity Is Hurting Young Women.

Valenti is American writer and blogger who founded feministing.com, an online community that acts as a forum for feminist news and opinions.

She is the author of three books, and currently writes a weekly column for The Nation magazine. Oh, and she was named one of The Guardian’s Top 100 inspiring women in 2009.

V-Card Vocabulary

Are you a virgin? If you have a yes or no answer to that question at the tip of your tongue, wait up. First, let’s define the word.

In The Purity Myth, Valenti points out that even if you spend an afternoon researching it at the Harvard library, you won’t be able to leave with a working medical definition of the term virginity.

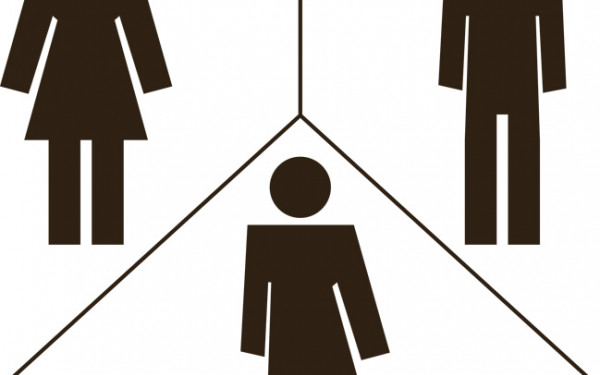

The meaning of the word is inevitably attached to the way one defines sex.

Some people consider oral sex as sex; others say an orgasm is required, while some won’t consider it sex unless both a penis and vagina are involved.

Valenti addresses the fact that, as a result, a definition for virginity that is both technically and culturally accepted simply doesn’t exist.

Some might argue that when a girl’s hymen—a fold of tissue that partially covers the external opening of the vagina—breaks, she is no longer a virgin.

These days, some women will undergo vaginal rejuvenation surgery to reconstruct their hymens and become “born-again” virgins.

Using the hymen as a standard of virginity is flawed, however, as many girls break theirs doing things completely unrelated to sexual activity, such as playing sports or inserting a tampon—and some girls are even born without them.

“It seems kind of ridiculous that all of this weight can be put on something that we don’t really know that much about,” Valenti said.

She argues that the ambiguity surrounding the word is problematic, especially where the female portion of the population is concerned.

“Culturally, we view the term to mean all sorts of different things that most often have a negative effect on women,” she said, adding that the way the word is often defined is unfairly exclusive.

“We think of it in terms of penetrative heterosexual sex, meaning that same-sex couples aren’t really having sex,” said Valenti.

Culturally, the term has been considered to mark an important right of passage—but Valenti said society would benefit from making the term less restrictive.

“I think it would be great if we had a way to talk about your initiation into sexual life, and let it mean of lot of things—I think if we had a little bit more variety and openness on that, there wouldn’t be this disproportionate focus on penetrative, heterosexual intercourse.”

The Purity Myth

Valenti believes that notion of virginity relating to the moral purity of women is incredibly detrimental.

“There is a lie that women’s sexuality has some bearing on who they are and how good they are as people, and that what we do or don’t do sexually is a marker of our moral character,” she explained, when describing the subject of her second book, The Purity Myth.

While Valenti addresses the issue specifically in an American socio-political context, she notes that the obsession with virginity is ubiquitous around the globe, and that manifests itself in slightly different ways.

In the case of the United States, she said, the movement is closely tied to conservative right-wing political ideology and its fear of losing power.

“You can see it in everyday policies that legislators try to pass in regards to women’s rights and health,” Valenti explains. “Whether it has to do with abortion legislation or sex education, the idea is very much this paternalistic view of protecting women from having sex.”

In her work, she references purity balls—events where young girls pledge their virginity to their fathers—as an unfortunate symptom of this way of thinking.

“By focusing on young girls’ virginity, you are still focusing on their sexuality, but the answer to fighting sexualization is not to use the objectification of women’s bodies,” she said.

While the sexualization of women may be seen as negative on all sides of the political spectrum, Valenti said the religious right’s means of combating it is more counterintuitive than anything.

“If you want to fight sexualization, then we need to tell girls that what they do sexually is not equal to what they are.”

She said if purity balls were really about father-daughter bonding, as advertised, then dads should consider becoming Girl Scout leaders, or play sports with their daughters.

“Teach her that her worth has nothing to do with her sexual choices but who she is as a person and based on the moral choices she makes.”

Her book further argues against the “myth” by using statistics to prove the ineffectiveness of abstinence-only education.

Still, Valenti said sometimes facts don’t suffice when it comes to fighting an ideological battle.

“That is why they don’t give up,” she said, referencing advocates of abstinence-only education. “Because it’s not based in science. They are not held down by any sort of fact.”

But while it may be a hurdle, Valenti says it’s important for people to keep moving forward by presenting well-researched arguments.

“The more studies that come out that say, ‘This isn’t working,’ the harder it is for them to ignore it,” she said.

Digital Feminism

While science is working in favour of feminism, Valenti said, so is technology.

With the inception of feministing.com, The Guardian has credited her with shifting the movement to a digital platform. The Columbia Journalism Review has praised the website for being “head and shoulders above almost any writing on women’s issues in mainstream media.”

Valenti said the online wave of feminism has been crucial in eliminating geographical boundaries that previously constrained the movement, adding that social media has done wonders for feminism.

“Before, if you were a feminist activist, it was because you were already interested in feminism—you sought it out,” she explained.

“But now, women are coming across it accidently. They do a Google search, and they find feministing.com, or they find a feminist Tumblr blog, and they relate to it. The potential for outreach is really incredible.”

A benefit, she thinks, that’s evidently showing.

“I think young women are seeking more action than ever before, and you see it all the time—young people are getting together and taking charge.”

ed1_722_682_90.jpg)

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

JillianPage_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

ED1(WEB)_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)