Unbinding the Binary

Gender Creativity Still Seen as Problem That Needs “Curing”

Nils Pickert was showered with Internet fame and “Father of the Year” titles after he wore a skirt in public to support his dress-wearing five-year-old son.

He didn’t like that his son’s choice of clothes had become a town-wide issue, and wanted to help the boy feel normal.

Pickert was one of Dr. Diane Ehrensaft’s examples in her lecture, From Gender Identity Disorder to Gender Identity Creativity, held Thursday night at Concordia’s D.B. Clarke Theatre.

In her talk, which focused on society’s changing attitudes towards gender, Ehrensaft said that, while parents have little influence over a child’s gender identity, they have a big impact on a child’s gender health.

“We as a profession have to take responsibility and apologize to generations of young people,” said Ehrensaft, a developmental and clinical psychologist.

Ehrensaft, who lives in California, is the author of Gender Born, Gender Made, a book that discusses gender as a spectrum, rather than two distinct girl and boy boxes.

Historically, psychology tried to “cure” children of gender non-conformity with a practice called reparative therapy.

Reparative therapy will become illegal in California starting Jan. 1, 2013; California Governor Jerry Brown, in signing the legislation into law, said that he hoped to relegate it “to the dustbin of quackery.”

“We need to go even one step further,” Ehrensaft said. “We need to legislate against any adult who tells a child what that child’s gender identity is, rather than waiting for the child to tell us.”

Canada still has a number of conversion therapy groups who attempt to use Christianity as a means to combat homosexuality—that is, to “pray the gay away.” Canadian law has only become involved enough to consider whether or not these groups should be allowed to hold charity status.

Ehrensaft said parents complain that small-town mentalities nullify a lot of the progressive approaches she advocates. When a community creates a culture that makes it potentially dangerous for a creatively gendered child to be what Ehrensaft calls their “true gender self,” her advice is: “tell [the children], ‘Society isn’t ready for what we know is right.’”

At a Beaconsfield, QC LGBTQ youth centre, the goal is to provide a space where kids can meet up and better understand themselves and others. Jessica Malz, who works at the centre, said that about half of the children are coming from families who initially have a hard time with accepting who they really are.

“They will tell them things like, ‘It’s a phase,’ or ‘You’re just experimenting. You don’t know who you are yet, you’re so young.’”

Ehrensaft strongly disagrees. “It’s up to the child to tell, not us to say.”

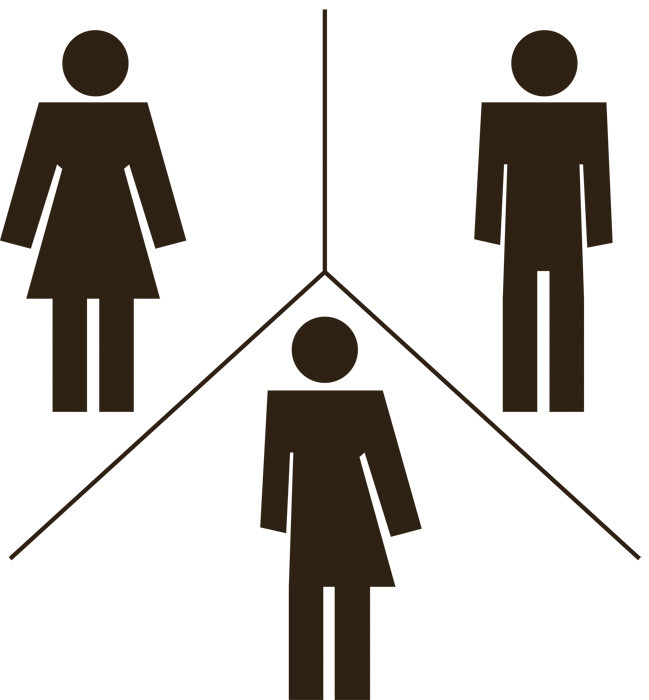

She said that children understand their gender through a “gender web” that’s made up of nature, nurture and culture. She added that, like fingerprints, no two children’s webs are the same.

It’s up to the child to tell, not us to say.

–Dr. Diane Ehrensaft

Gloria, a lecture attendee, has an 11-year-old transgendered son and said that there is a major shortcoming in how Quebec’s education system addresses diversity.

“No one wants to touch this,” she said. “Can we talk about different families? And that it’s okay?”

While the rise in media coverage of the issue lately might suggest an upswing in gender non-conforming children, Ehrensaft said that the amount of people who are born this way has been consistent through generations.

The only thing that has changed, she said, is the way society approaches the issue and the degree to which people are compelled to bury their true selves.

“At three it was pretty clear—he’d say, ‘I’m a girl,’” Gloria said of her son. “But as they get older they get wiser. They know they have to suppress.”

Earlier this year, a school district in Virginia looked at banning cross-gender dressing. It was proposed as an anti-bullying measure, but the attempt to stop boys from wearing girls’ clothes died in a storm of controversy.

“With the activist involvement of the gender creative community and its allies, we should expect to see more and more libratory practices regarding gender and more negative sanctions against those who attempt to legislate or police gender,” Ehrensaft said.

A kindergarten teacher stood up during the question-and-answer portion of Thursday’s lecture to ask how she could stop her students from bullying one boy who dressed differently from the rest.

She said that teachers are trained on how to address bullying issues dealing with skin colour, but get no training when it comes to handling gender creativity.

It’s the kind of environment that creates gender constructions children have to adopt. In the case of not being accepted at school, some children Ehrensaft has spoken with become what she calls “gender by season.”

One example is a child who identified as “school girl/summer boy.” The child was not comfortable transitioning at school, so they had two gender identities, depending on what environment they were in.

Still, “trying to ‘cure’ gender nonconformity is alive and well among mental health professionals today,” Ehrensaft said.

_(1)_600_375_s_c1.png)