Airbnb Marks a New Gold Rush in Plateau Mont-Royal

Airbnb May Be Beneficial For Landlords, But It’s Inducing Gentrification At Accelerating Rates

Plateau Mont-Royal is a popular place for students to live and play, home to neighbourhoods such as the Plateau and Mile End, as well as some of the city’s most revered cultural touchstones.

No secret to tourists looking for a taste of Montreal’s joie de vivre, the borough is also a premier Airbnb hotspot—which some experts suggest is putting an upward pressure on rents. It is tempting for landlords to accommodate tourists rather than residents in a landscape of increasingly scarce housing. Long-time borough-dwellers are threatened by displacement, while disheartened students may be forced to look elsewhere.

Tim Forster, editor of Eater Montreal, works out of a fifth-floor Mile End studio, an emblem of the neighbourhood’s fame as a creative hotspot. “This is a shared studio. Everyone [else] is doing artwork,” he said. “There’s space for 13 people.” But he used to live around the corner in a building on Park Ave. near Bernard Ave.

Surrounded by vibrant spools of yarn, an orange-sweatered dog and a view of Mount Royal, Forster shared the story of his move. “I’d been living there for close to two years by the time the eviction came around,” he said. The previous owner had been older and easy to deal with, but when the building changed hands, the representatives of the numbered company that purchased it sent out eviction notices by registered mail, giving the required six months’ warning and a promise of three months’ rent, plus moving expenses.

“We negotiated, and they to our surprise outright said, ‘Oh, well we want to make the building Airbnbs.’ […] This was like one-on-one in the apartment. They came to the apartment […] to avoid going to the Régie [du logement]. We felt that we were in a position of power because I was pretty sure that the eviction was invalid.”

A tenant generally has the right to keep their home if they conform to obligations such as paying rent on time and not disturbing other tenants, but there are exceptions delineated by the Régie du logement, Quebec’s rental housing tribunal. An apartment’s owner or their close relative can move in at the end of a lease, and the owner can take possession in order to “divide, enlarge, or change the destination” of a unit, the latter term meaning to change its purpose.

Had Forster’s eviction proceeded to the Régie, the landlord would have had to provide evidence demonstrating the validity of their stated intentions and any legal permissions they would need. According to Forster, the landlord had no intention to move in, enlarge or divide the unit and appeared not to have obtained a permit to operate a tourist accommodation—an electronic entry system has been installed at the address, but there does not appear to be a classification sign posted as would be required according to Tourisme Québec. A spokesperson for the Régie, Denis Miron, did not confirm whether an eviction like Forster described would have been illegal but reiterated the leaser’s burden to show they truly intend to “divide, enlarge, or change the destination of the dwelling and that [they are] permitted to do so by law.”

“We negotiated [and] I pushed quite hard on them. I bluffed it and said I’m a journalist, I worked at city hall […] I’ve been to city hall and have a rough understanding.” In the end, he suspects that he and his roommate, with whom he split a settlement of $10,000, fared better than the building’s other tenants.

“Part of the reason why they were willing to budge and give us more money was because the eviction notice they delivered to us as registered mail was addressed to someone that was no longer on the lease.” For a lease longer than six months, tenants are entitled to six months’ notice prior to the end of the term of their lease and have a month to object to the eviction.

Forster has since found his old building on Airbnb, where four of its apartments, nearly half, are currently listed on the platform. All four are two-bedrooms, and the current price of each at the time of publication hovers around $75 per night on weekdays, plus a one-time cleaning fee of $80.

Prices in the same building rise as tourism season arrives. The nightly prices can go up to $138, plus cleaning, when booking for weekdays in early May. Prices later in the month go to $214 per weekend night. When staying on a weekend in mid-June, the price hits $235 per night plus cleaning, while Tuesday to Thursday early in June goes for $154 per night. Some of the revenue funds Airbnb, as the company typically takes a fee of three per cent from hosts.

It is difficult to calculate what one unit in Forster’s old building will earn in peak season. But averaging even the lower June figure over thirty days, the unit generates a few thousand dollars, assuming two-night stays are booked for close to the entire month.

Forster and his roommate had been splitting a monthly rent of nearly $1,000.

The apartment is one of thousands no longer available to Montreal residents looking for an affordable home within commuting distance from school or work, serving instead the legions of tourists the city attracts each year. The reviews are overwhelmingly positive, with guests raving about the location in a good neighbourhood close to downtown and the suitability of the units for families.

One guest noted that the adjacent apartment is an Airbnb, so travellers can enjoy meeting each other.

Due to his work, Forster is an expert on the restaurant and café scene that forms part of the neighbourhood’s appeal to visitors. He said he has seen changes in the neighbourhood since he started spending time there in 2013 and fears for its future. “I would not want to see [Mile End] converted into a permanent tourist neighbourhood, and I think that’s going to effectively eliminate the character that drew the tourists there in the first place.

“It’s really hard to separate gentrification from the tourism. […] If something is causing problematic gentrification, it’s […] a switch from something like housing to being permanent Airbnb,” Forster said.

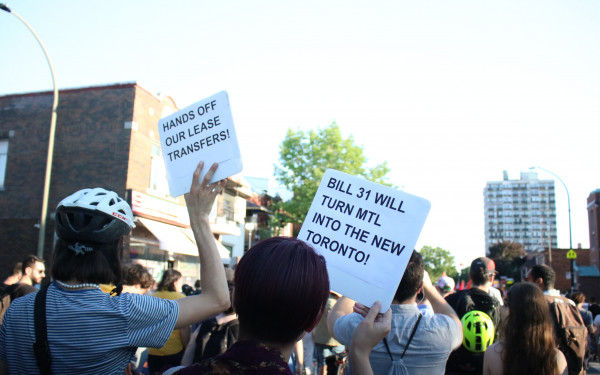

Concerned by the proliferation of full-time tourist accommodations in the borough, Plateau Mont-Royal recently introduced regulations that will limit new permits to stretches of St. Laurent Blvd. and St. Denis St. The by-law was adopted in December in an attempt to preserve quality of life for residents and protect the borough’s housing market.

The borough notes that it does not have the tools to stop illegal tourist residences, which include those offered on a regular basis without a certificate required by provincial law.

A 2017 report from the Front d’action populaire en réaménagement urbain shows the vacancy rate in the borough fell from 2.3 per cent to 1.1 per cent between 2016 and 2017. This is a period which saw a large increase in Airbnb listings in major Canadian cities, according to a report published the same year by the Urban Politics and Governance research group at McGill’s School of Urban Planning.

That report highlighted that some Montreal neighbourhoods have seen two to three per cent of housing stock “converted to de facto hotels,” and that in some cases whole buildings “have been converted by their landlords into full-time Airbnb operations.”

“[Gentrification] raises rents and makes cities less affordable for […] people who lived here for decades,” explained Odile Lanctôt, a researcher tasked with updating 2016 research around Airbnb by the Comité logement du Plateau-Mont-Royal, a tenants’ rights in the borough.

Gentrification can be hard to quantify and its causes are complex, but the CLPMR believes it is an ongoing process in the borough, as demonstrated in their 2014 report on the subject.

A 2018 report comparing 2011 and 2016 census information shows a 15 per cent increase in the median income of borough renters in Plateau Mont-Royal, while rent went up 16 per cent. This is nearly twice the increase of Quebec’s consumer price index—a measure of inflation—over the same period.

The CLPMR characterizes Airbnb as a contributing factor to gentrification. Their 2016 report states that, “Airbnb indirectly pushes homeowners to oust tenants in order to rent accommodations to tourists and make more profit,” and that the “arrival of better-off people and tourists in the neighbourhood opens up new bars, restaurants, cafés, etc, which increases the cost of living in a global way. In this sense, Airbnb reinforces the gentrification of a neighbourhood and the lack of affordable housing.”

Their solution? “Ban Airbnb,” exhorts the cover of a brochure they produce. These are arranged in a neat stack on their office’s literature table, on which the small staff brews coffee in a cheap plastic machine. The group estimated in 2016 that as much as five per cent of the rental housing market in Plateau Mont-Royal was being diverted for tourist use on Airbnb.

“It just destroys neighbourhood life. You don’t know your neighbours. They’re always different, they don’t care about you, you don’t talk to them. It’s a way of living.” — Odile Lanctôt

Many Airbnbs operate illicitly in Quebec. A 2017 report out of McGill’s School of Urban Planning indicated that, “Fewer than one per cent of Montreal’s full time listings [were] certified and paying the accommodation tax,” with only a handful of violations handed out—none of which were in Montreal. Enforcement of the rule was transferred to Revenu Québec in June, resulting in nearly one thousand warnings being issued across the province by the end of November according to Mathieu Boivin, a spokesperson from the agency who emphasized a focus on tax compliance.

“Airbnb growth [in Plateau Mont-Royal] is completely outpacing new constructions and [is] actually reducing net available housing stock,” noted the McGill report, meaning in spite of new homes being added to the neighbourhood, there’s still a decline in housing available for people to live in.

The CLPMR’s office receives field calls every day from residents frustrated by issues related to the platform. “[The guests] just throw garbage everywhere. And there’s the sound of people checking in and checking out, and the parties […], apartments rented to tourists who want to do bachelor parties” Lanctôt said.

“It just destroys neighbourhood life. You don’t know your neighbours. They’re always different, they don’t care about you, you don’t talk to them. It’s a way of living.”

She said tenants being evicted or pressured to leave to make room for Airbnbs is a big problem in the borough.

Richard Stafford, 72 years old, is fighting to keep his Pine Ave. apartment of three years, located around the corner from a building where he lived and worked as a superintendent for more than 20 years.

“It’s sort of stressful,” he said. “I’m a little too old for this. […] I’ve lived in different places in my life, but when you get old you want something stable.” He’s paying $600 now, but said if he moves into a neighbouring building where he can get a comparable apartment for $800, he is worried the same thing could happen again.

“It’s like the gold rush,” he said. “Everybody’s jumping on it.”

Most of his fellow tenants have taken money to vacate or been evicted by other means, he said. “The former landlord [always] let them get […] behind on rent, so they were used to that. That’s how they got rid of three or four people.”

“[As for the others], if you have a minimum wage job, or you’re on welfare […] and they offer you $4000—I remember when I didn’t have any money at all. You take the $4000.”

The renovation of vacant units has been a nightmare, he said. “Before they were closing the door and asking very nicely [if they were] making too much noise. Now they’re just leaving the door open.”

In the summer, Stafford saw, “Constant circulation [of tourists]. “

“It was like a hotel lobby when you’re coming in the entrance.”

The apartments that have been renovated, he said, are rented to short-term tenants during the winter months and put on Airbnb in the lucrative summer season. He says the character of the building has changed as a result. “You’re getting all the BBs—bourgeois bohemians.”

Meanwhile, Stafford said prices in the area have gone up and complains he has nowhere to go unless he moves into a comparable apartment in a high-rise for $1100, that or he feels he’ll risk the same fate in a smaller building.

Online listings on other websites show that units from the building have been advertised for short-term leases and tourist bookings. On one, the host’s profile compares his apartments to hotel rooms, citing things like clean sheets and towels.

“I had an opportunity,” explained Dana Zhou, who operates more than 10 Airbnbs and employs a cleaning team and an assistant.

“There was an apartment for rent, and we were friends with the owner, and they asked me if I was interested in renting it on Airbnb. I was like, ‘Sure, why not.’ I was doing it just for fun. We started with one, like a year and a half ago. And then it just went on. There was another one in the same building, so I took over.”

For each of her properties Zhou said she either represents the owner or has all the apartments in the building for rent.

“I don’t have to hide it from everybody,” she said. “I don’t have to tell the guests, ‘Don’t tell people you’re in an Airbnb, just say you’re my friend.’”

“That happens all the time.”

She has faced some complaints about parties but insists these are rare and have never been serious. That’s not the only drawback: hosting has gotten more and more competitive.

“[Listings] are nicer and nicer. Nicer, like really nice. And not expensive.” The goal is to stay afloat until the bountiful tourist season, between March and September, during which prices go up and her apartments will be “98 per cent full.”

Zhou believes much of the market is operating in contravention of the law.

“There’s so many, so many [Airbnbs] right now, and none of them have permits,” Zhou said. “I would say a few of them do, but very, very few. Maybe a hundred out of a thousand on the Plateau. It’s like a free for all right now.”

Most of Zhou’s listings are in Plateau Mont-Royal, where she also lives. “If I were to come to Montreal, I would stay [here]. It’s quite family-oriented.”

Stafford says he just wants to stay in the community, reflecting on his fondest memories. A dedicated customer who has been going to Shish Taouk on St. Laurent Blvd. and Prince Arthur St. E. everyday for about 20 years, he said, “It’s like family for me.”

Around the corner from Stafford’s favourite restaurant, it is not uncommon to see people dragging luggage or screaming drunk on pedestrian-only Prince Arthur St. E. Get out of the commotion: dip into a dépanneur. Inside, you’ll find the usual scene. People are clamouring for chips and crackers, or perhaps another beer. Next to a stack of warm Pabst Blue Ribbon, you’ll find an electronic box mounted to the wall. If you’ve made arrangements, you’ll need only your code. Inside each of its 19 compartments? A key, of course. Enjoy Plateau Mont-Royal.

1_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)