“A Work of Memory”: The Dhakira Collective presents the North African Queer Film Festival

A wealth of films displayed by queer SWANA artists

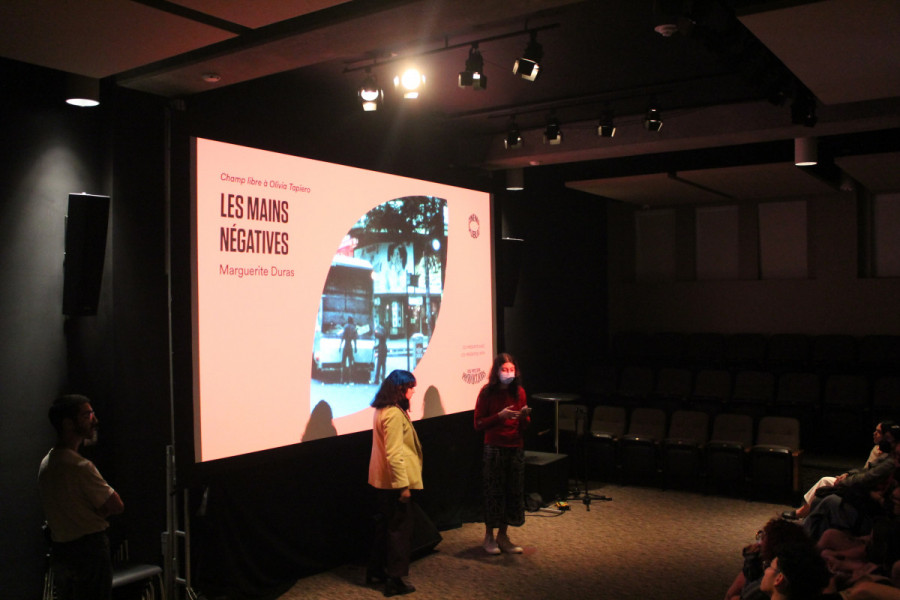

As the lights dimmed in Casa d'Italia—a quaint, intimate venue by Jean-Talon metro station—a swarm of enthusiastic film-goers seized their seats.

Drawn by the enchanting film program exploring the kinship of North African and South Asian Queer Gazes, spectators were anticipating what was to come.

From Sept. 7 to Sept. 23, Cinéma Public is presenting the second edition of the North African Queer Film Festival (NAQFF), hosted by the Dhakira Collective.

The Dhakira Collective is a platform dedicated to preserving and exploring non-Western cinema, with a particular focus on films and cultural artifacts from the Maghreb and South West Asian (SWANA) region.

This year, they held their second edition of the NAQFF, encapsulating a film program with queer aftertastes and hints. Additionally, a discursive panel took place, featuring themselves, queer SWANA artists, and the audience.

The two founders, Bouchra Assou and Gaïa Guenoun—both of Moroccan origin—have expressed that their work within the collective extends to art and music. Dhakira is driven by a mission to uncover and promote cultural gems that might be overlooked or marginalized, such as North African cinematic heritage.

Dhakira’s journey began with a desire to create a digital archive of cinema, art, and music. Assou and Gennoun recognized a lack of visibility for North African and Arab cultural works and aimed to change that. They began sharing online content and founded the NAQFF to showcase politically or artistically significant films facing wider audience challenges.

On Sept. 7, the first night of the film festival featured Brita Landoff's 1993 documentary "A Little for My Heart, A Little for My God," offering insight into Algerian female musicians, the Medahates, who perform exclusively for women. Dhakira hosted a discussion on queerness in North African performances with Algerian dancer Esraa Warda and Tunisian dancer Achraf El Abed.

“Maybe the biggest impact that our film festival has here in Montreal is that a lot of the queer spaces are very white; and not necessarily accessible to queer North African or Arab demographics. So, it’s nice to have a space that is just for us, where we’re not necessarily fetishized or tokenized.” — Bouchra Assou

The second screening night was even more crowded, with people sitting on the floor for an intimate experience of utopian visions of queerness. Queer Utopias, the name given to that night’s screenings, showcased films blending sci-fi, fantasy, poetry, queer icons and minority portrayals, providing critical societal reflection.

“We both wear many hats since there are just two of us,” explained Assou. “I focus on festival programming, grant writing, partnerships, communications, and social media. Gaïa [Guenoun], on the other hand, coordinates, handles the festival's visual identity, works closely with the graphic designer, manages technical aspects, and even curates panels".

Assou explained that the Dhakira Collective's inception was quite spontaneous. She simply shared her idea with Guenoun, expressing her desire to create a digital archive for cinema. Her motivation stemmed from a longstanding passion for film and her realization that even she had struggled to discover the rich cinematic heritage of Morocco and similar artistic expressions.

Both founders of the Dhakira Collective come from different cultural backgrounds. Guenoun, with early exposure to film education in Casablanca, developed a passion for cinema, aiming to challenge the dominance of Western-oriented film distribution in the Maghreb. She emphasizes the importance of preserving marginalized films integral to the region's cultural history.

Assou, initially a classic cinephile, later explored Arab films and realized the challenges they faced, including censorship and limited preservation efforts. Dhakira revives culturally significant films, even though many are archived in Europe, making access limited. Their mission is driven by their commitment to memory and representation.

“You never hear about cinema from North Africa even though there’s a great heritage and a great tradition of filmmaking,” added Assou.

“People are now seeing themselves represented in ways they never have before. I’ve personally never seen myself on screen like this. We programmed many of these films without even watching them first. With each film, I see myself, my siblings, and friends from back home.” — Gaïa Guenoun

The collective operates with a commitment to accessibility, making all their events and screenings free to ensure that people—particularly from marginalized communities—have access to these cultural offerings. Their impact extends to providing representation and a safe space for queer North African and Arab audiences who may not find themselves fully included in other spaces.

Assou further explained that in the future, she plans to open submissions for unique insights. Accessing hidden gems, such as Mauritanian films addressing queer themes, has been challenging due to limited online availability. Open submissions are seen as a way to bridge these gaps and connect with enriching creators and works. Similarly, she mentioned previous difficulties in finding Sudanese films in a past edition.

“Maybe the biggest impact that our film festival has here in Montreal is that a lot of the queer spaces are very white and not necessarily accessible to queer North African or Arab demographics. So, it’s nice to have a space that is just for us, where we’re not necessarily fetishized or tokenized,” said Assou.

Guenoun highlighted that the films they feature address themes of sexuality, with Vénus Rétrograde being particularly provocative yet respectful of people's realities. She rejects the notion that being queer and respecting tradition or cultural heritage are mutually exclusive, emphasizing that this misconception extends beyond the Muslim or North African communities.

"People are now seeing themselves represented in ways they never have before. I've personally never seen myself on screen like this. We programmed many of these films without even watching them first. With each film, I see myself, my siblings, and friends from back home," Guenoun said.

Djazz, Bousnina attended the festival on Sep.10th, the day of the Queer Utopia screening:” I personally really enjoyed the fact that we [the audience] were all from different regions, it was good to see people who looked like me on the screen who were not necessarily of a fatalistic scheme, and terminally, treated like something to get rid of”, Bousnina explained.

The Dhakira Collective is a testament to the power of grassroots efforts to preserve cultural heritage, promote inclusivity and create meaningful change in the world of art and cinema. They plan to expand and seek more funding for future festivals, including potential locations in Morocco and elsewhere. They aim to establish recurring events, focusing on North African and queer cinema, and create their streaming platform to promote underrepresented voices in film.

“Dhakira means memory,” Assou said. “I think that a lot of what we do is a work of memory [...] a lot of preservation and archiving, and making sure that things are not forgotten.”