A Vision for a Feminist University

Inclusivity Among Goals For Simone de Beauvoir Institute

In the 1970s and 1980s, Norwegian politician Berit Ås campaigned for the creation of a feminist university.

It was a radical concept for the time. After ten years canvassing for funds and support, lecturing on the topic and hunting for the perfect location, her dream was realized in 1985. A converted old-age home in a village in central Norway opened as the Stiftelsen Kvinneuniversitetet. Despite Ås’ intentions to explicitly identify the university as a feminist institution, the title translates as “The Women’s University.”

In the 30 years that have passed since Ås’ work, the term “feminist university” has remained largely dormant. A Google search only spits out few garbled results.

That is, until Kimberley Manning, principal of Concordia’s Simone de Beauvoir Institute, revived the movement last year. She has been exploring the concept since June.

“It really started off as a question to explore, an aspirational vision,” Manning said in a telephone interview. “It was a way to prompt discussion, to think about questions of equity in the university and the surrounding community, and the way in which gender, race, transphobia and class are treated.”

The Critical Feminist Activism in Research project at SdbI was born out of these questions. It aims to “begin a reimagining of how our university works and who it works for,” C-FAR’s website explains.

Concordia graduate students Meghan Gagliardi, Annick Maugile Flavien, and Finn Purcell have been working with Manning for months, using an intersectional feminist framework to look at how equity, representation and inclusion can be improved both on campus and in the wider Montreal community.

“Concordia has this reputation as the people’s university in a lot of ways,” Gagliardi said. “Our work is about speaking to people who might not easily fit into the way the system works now and talking about how we can better reach their needs.” The team is currently putting the finishing touches on a student survey that will ask undergraduates what their needs are in regards to inclusion.

C-FAR projects include a new feminist summer institute, which will take place from May 15 to May 19, led by Manning’s SdBI colleague Dr. Geneviève Rail. Students can gain three course credits for participating. It will also be open to the public.

Under Manning’s direction, a year-long, six-credit course called “The Feminism University Seminar” will open for undergraduate students in the 2017-2018 academic year. Throughout the course, students from both inside and outside of the SdBI can contribute to one of five social action projects.

These include investigating racism in elementary schools in Outremont and gender disparity in Concordia’s electro-acoustics department. Others will look at developing gender and sexuality alliances in local schools, and integrating anti-racist women’s studies courses in local high schools. The final project will work closely with the newly-established Indigenous Directions Leadership Group.

“We continue to live with the legacy of white liberal feminism largely being an exclusive project” – Kimberly Manning

“That is the one project out of five that still needs the most definition,” said Manning in an email. “We have had a general discussion about focusing on ‘decolonizing the university’ by helping to educate faculty, but haven’t gotten further than that yet.”

C-FAR is also looking at how they can work with the competitive Communications Department to diversify prospective students applying.

Inclusiveness is central to Manning’s vision for a feminist university. “We continue to live with the legacy of white liberal feminism largely being an exclusive project,” she said. “We need to make race essential to what we are doing.”

Key to this inclusiveness is the concept that students involved in any projects are duly rewarded for the meaningful, productive work that they are doing.

“For me, burnout is the opposite of living a feminist life,” Manning said. Her own experience of integrating advocacy and activism as the parent of a trans child into her academic work at the SdBI gave her first-hand experience of the importance of “adding in, rather than adding on.”

C-FAR’s projects involve arming students with transferable, tangible skills and school credits for hard work.

C-FAR has incorporated this ethos into its project planning. “There are so many students, faculty and staff already working on issues of equity and inclusion. Rather than create new projects that are doing the same thing, we’d rather partner up and share resources and collaborate,” Gagliardi explained. She and her colleagues work closely with the Centre for Gender Advocacy and Concordia’s Committee for Equity and Visibility in The Academy.

According to Manning, feminism, in all its forms, is central in creating change in today’s “frightening” socio-political climate. “I’m actually optimistic, in this moment of crisis, that we at Concordia can offer a different and better vision of how we live together and how we can thrive and grow as learners and as members of a very rich community in Montreal.”

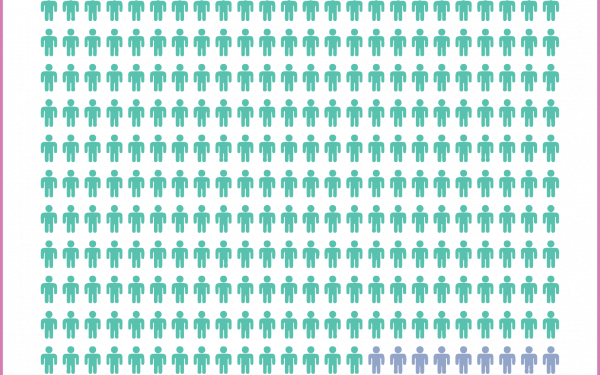

According to Concordia spokesperson Marisa Lancione, enrolment in women’s studies has grown by 90 per cent in the last ten years—a sign, according to Manning, that there is a current “need, desire and real engagement with feminism.”

Manning will give a six-minute discussion on her concept of a feminist university at a Concordia University Part-Time Faculty Association MircoTalk called Feminism Matters on Feb. 7. Maria Peluso, ex-president of CUPFA, acknowledged that the event is the result of conversations with Manning and the “movement to create a feminist university.”

The interdisciplinary event includes presentations from part-time faculty, full-time staff and students, including journalism professor Linda Kay, whose research looks at pioneering journalists, Alex Antonopoulos, part-time faculty member at the SdBI whose research focuses on addiction and transmasculine embodiment, and pk langshaw, Design and Computation Arts chair.

_854_1280_90_(1)_600_375_90_s_c1.jpeg)