What’s White, and White, and White All Over?

ASNE Numbers Cause for Concern

Facts are a funny thing.

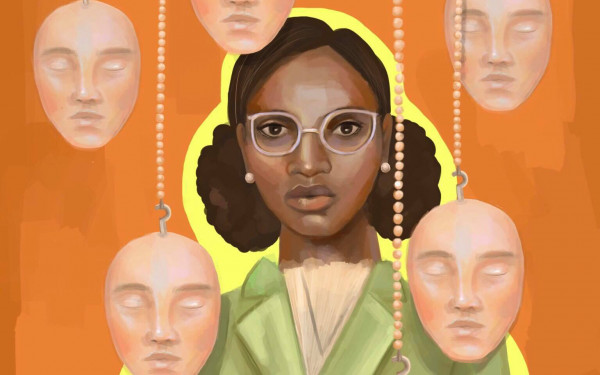

Despite the fact that a significant portion of the Canadian population is comprised of visible minorities, the reality is that there is a startling lack of minority representation in newsrooms across the country. So even though the reality of an increasingly diverse workforce is something that must be realized, many are still excluded from the media.

What’s worse is that studies of diversity in Canadian newsrooms are few and far between, so finding out about these disparities is hard to do.

Among the latest studies is a 2004 investigation by John Miller of Ryerson University, which reports non-whites comprised 3.4 per cent of the country’s newspaper workforce while representing about 17 per cent of the general population.

In plainer terms, the employees of the 37 papers that responded to the study were made up of 2,119 people, from which only 72 were visible minorities. That’s not a typo—only 72 visible minorities could be counted out of over 2,000 employees. It’s a number that unquestionably fails to properly represent the diversity that can be found in Canada, and it gets worse.

Miller conducted a similar study 10 years prior, and had recorded a 50 per cent drop in “commitment to hire minorities.” In 1994, 26.8 per cent of the editors who answered felt a “very strong desire to hire a diverse staff.” In 2004, that number rested at a mere 13.5 per cent.

Also on the rise was the number of papers with an all-white staff. In 1994, 39 per cent of the 41 participating papers had no visible minorities on staff, while 59 per cent of the study’s 39 publications had no minority presence in 2004.

The fact that many newspapers are becoming increasingly staffed by white individuals, coupled with the fact that only 13.5 per cent of newspapers who responded felt the desire to hire minorities, means that things won’t necessarily get better as people become more tolerant of differences.

The American Society of News Editors (ASNE) recently released the results of its annual census, aimed at monitoring the number of non-white reporters in the industry. While there are 6 per cent less reporters overall than last year, visible minorities made up 12 per cent of the workforce—a decade-long trend—while also representing 30 per cent of the country’s population.

According to Gwyneth Mellinger, author of Chasing Newsroom Diversity: From Jim Crowe to Affirmative Action, the ASNE itself was very slow to warm up to minorities in the newsroom, including women.

The organization was quite exclusionary up until the 1950s—so much so that not even U.S. president Lyndon Johnson’s blistering Kerner Commission spurred immediate change. Among the report’s findings: “The scarcity of Negroes in responsible news jobs intensifies the difficulties of communicating the reality of the contemporary American city to white newspaper and television audiences […] But full integration of Negroes into the journalistic profession is imperative in its own right.”

Ten years elapsed between the publication of those words and the inception of ASNE’s Goal 2000, in 1978. But Mellinger calls the initiative, which aimed at reaching parity with the U.S.’s minority population by the year 2000, “noble but naive and uninformed.” Unable to reach its aim, ASNE eventually pushed back its target to 2025.

In Within the Veil: Black Journalists, White Media, author Pamela Newkirk says African Americans were at first hired to cover events white journalists could not blend in to, such as Black Panther rallies. They were considered not smart enough to do the job, so while they collected details from the events—a publication went as far as sending a black circulation truck driver to cover a story—white journalists wrote the articles.

Black reporters’ ability to be objective about other African Americans was also questioned. In one instance, Michael Cottman, a black journalist at New York Newsday, was asked to go after David Dinkins, New York’s first black mayor. “Show us you can bust his balls,” Cottman’s editor told him.

As a matter of fact, some studies show hiring minorities doesn’t necessarily change the complexion of the coverage. Blacks still dominate the entertainment and crime pages even though, from a quantitative standpoint, white individuals commit more crimes. Non-white reporters who do manage to get newspaper jobs are merely expected to toe the company line. Hiring sprees alone are thus inconsequential, save for perhaps momentarily fending off the Al Sharptons of this world.

Clearly, the ratio between white men and non-whites isn’t going to significantly change any time soon. But the coverage of North America’s changing communities is more pressing than ever, and still leaves a lot to be desired for an industry wanting to be relied on for its ability to address reality.

Some publications have tackled this problem exemplarily. At Gannett Company, newspapers, including USA Today, try covering all the bases. Despite the group’s admitted failure to attract a substantial number of minority reporters, it’s changed the way non-whites are covered by deliberately looking for articles and pictures depicting minorities in a positive light.

Some may describe such a policy as unbecoming of any self-respecting publication. However, given the longstanding history of lopsided attention given to black criminality, the “natural way” has not proven any fairer.

Going the extra mile in the other direction is really a proportional means to counterbalance what’s been achieved to date.

While there have been some positive strides made, there remains a long way to go. At the time of the 2004 study, The Montreal Gazette actually excelled in its portrayal of minority groups. Miller called the paper “the only exception” among six Canadian newspapers to cover minorities reasonably, with respect to the number of stories and how diverse they were.

Despite some strides on the front of female employment, then-Gazette editor-in-chief Andrew Phillips said in a 2006 interview, “[W]e’re not a bad reflection of our readership,” but “[W]e’re not a great reflection of our community.”

And that’s coming from “the only exception.”

Concerned yet?