Wandering into the periphery

The Wandering Eye Project displays the world through a symbolic lens

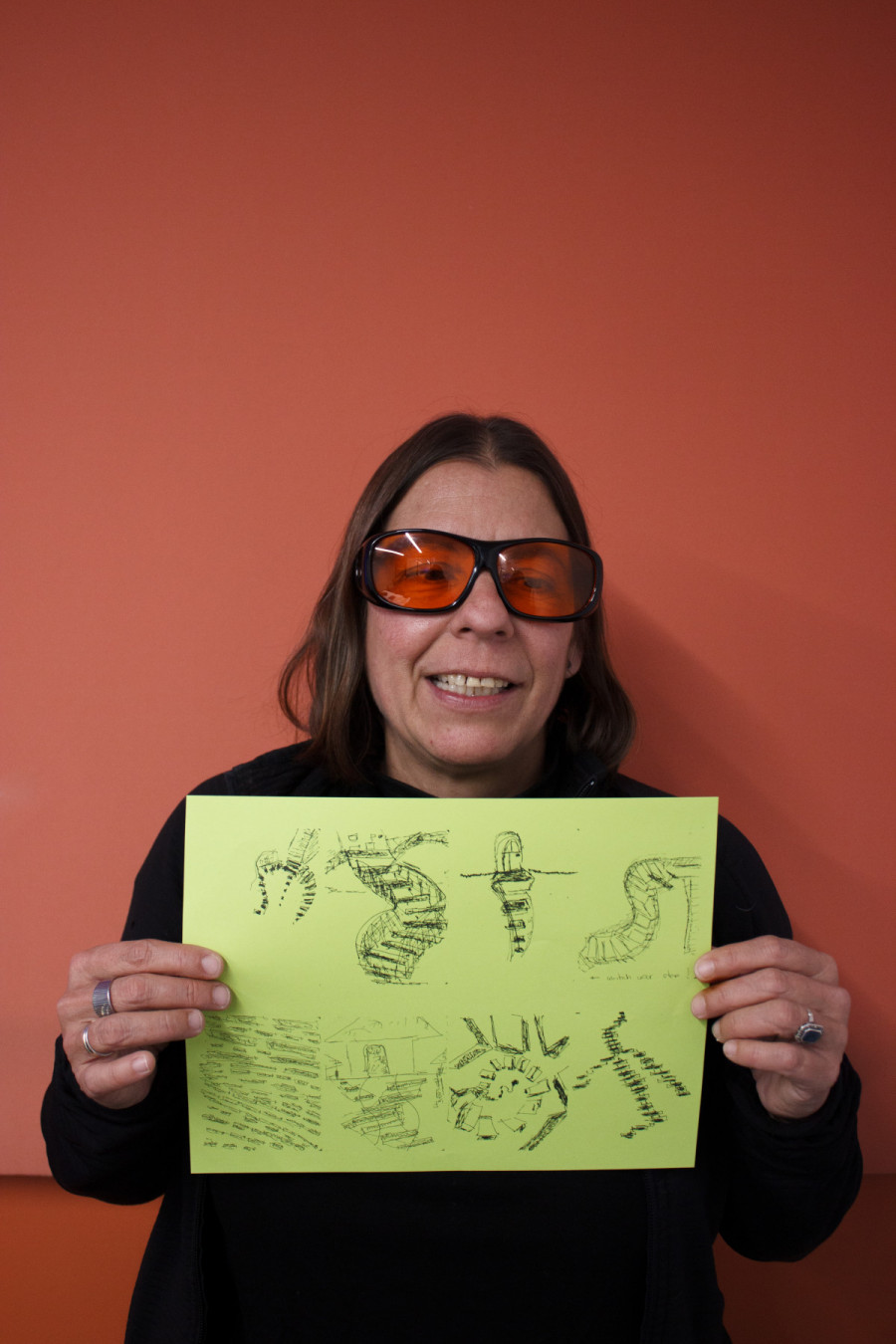

Brígida Cristina Maestres Useche spreads a jumble of well-loved sketchbooks across the table in front of her at the Concordia University Sir George Williams campus, their dog-eared pages brimming with drawings.

In Montreal from September to December 2024 as a visiting scholar from the Open University of Catalonia, her sketchbook reveals her recently completed collection of stair drawings inspired by her strolls around the Plateau-Mont-Royal.

“I’ve been very impressed by the stairs,” Maestres Useche says, describing how the staircases remind her of squid legs. “It's as if a huge squid has swallowed all the houses in Montreal.”

Reimagining how we view the world is central to Maestres Useche’s The Wandering Eye Project. The project seeks to challenge social constructions of the “correct” way to see with our eyes, by introducing the peripheral world using drawings, video and percussion to showcase the world as she perceives it.

“The peripheral world concerns the fact that my peripheral vision is better than my central vision,” Maestres Useche says. “I am trying to depict more or less the way I see.”

For Maestres Useche, the peripheral world is a metaphor for the way her own vision—and perspectives like hers—are often pushed to the side by science. She critiques what she calls “ocularcentrism.” She describes this as the tendency for science to examine vision using a scientific method centering photographic models of vision. This creates a blind spot where vision falling outside this paradigm, such as her own, is not validated.

The Wandering Eye Project began in 2015 when Maestres Useche asked her friend, photographer Ángela Bonadies, to help her capture the world through her own eyes.

“The challenge was to describe it in a positive way, not using blurred or fused,” Maestres Useche says. “You know, these negative categories.”

The end result includes old distressed film obstructed with light splotches, wavy distorted images of blue tile and colourful geometric drawings layered over a face. The result touched Maestres Useche because it reflected so accurately the way she sees, and inspired her to expand the project to involve other mediums.

According to Maestres Useche, the peripheral world is more than just vision; it's a metaphor for perspectives overlooked.

“If science looks at the periphery, it's in the sense of underdeveloped countries that are the periphery; Black people, the others,” Maestres Useche says. “There's the prototype of normality, and then the others.”

Growing up in Venezuela, Maestres Useche was known as the “girl with thick glasses.” Doctors never used the term “disability” to describe her condition, but this lack of label meant there was no institutional support. Her parents were told she may not even be able to finish her schooling.

Maestres Useche describes how on one hand, it was tough as she was forced to deal with things on her own. On the other hand, she was plunged into the world, which helped her adapt and learn to survive.

Yet as she grew older, Maestres Useche quickly discovered the label of disability comes with a whole new set of challenges.

In 1998, after completing a BA in sociology, Maestres Useche moved to Barcelona to complete her PhD in social psychology. There she encountered what she describes as “the other side of the problem” regarding societal discourse on disability.

In Barcelona, institutions exist to help people like Maestres Useche. However, they use labels like “low vision,” “disabled” and “visually impaired” to define her.

“They always need to acknowledge you as a disabled person,” Maestres Useche says. “Even though these are institutions that are attempting to help, or balance society, you are kept by these policies—you cannot live your life [outside of] them.”

As a social psychologist, Maestres Useche now explores how disability policies and labels like “disabled” shape how those affected see themselves and how others perceive them. Through her work, she illustrates how the eye can construct and define its own reality.

“In my case, with my vision, I didn’t lose anything. I’ve never seen otherwise,” Maestres Useche says.

The artist also experiences nystagmus, giving her a “wandering eye” that can capture multiple images at once. In 1988 she underwent cataract surgery in her right eye, and strabismus in her left eye. This operation left her with double vision, and she began seeing the world in two dimensions. Instead of feeling limited, she embraced imagination as a tool to “dimensionalize” the world.

This approach is what she calls “the animism of the wandering eye.” For her, animism means giving a soul to something that's not objectively there, connecting the senses to the imagination and using imagination to dimensionalize the world.

“Even though these are institutions that are attempting to help, or balance society, you are kept by these policies—you cannot live your life [outside of] them.” — Brígida Cristina Maestres Useche, The Wandering Eye Project creator

Arlene Sanchez, a PhD student studying social and cultural analysis at Concordia, met Maestres Useche during the first week of her doctorate. She describes those first weeks as the beginning of a journey of discovery of how she sees and interprets the world.

“Distorted lines being drawn in a big notebook caught my attention. I started to follow that black ballpoint pen with apparently no direction other than maybe the joy of moving through the notebook,” Sanchez says. “Entering to the wandering eye of Brígida is also as moving apparently with no direction other than the mere joy of moving freely.”

For Sanchez, The Wandering Eye Project shows the importance of creating work that puts your own voice and life experiences into the world. It's also a reminder that it's cool to simply have fun.

“It's cool to just be wandering,” Sanchez says. “I will not follow what people say.”

Sanchez describes how she and Maestres Useche took a walk together through the Plateau-Mont-Royal, allowing their eyes to wander to the peripheral as they saw those squid-legged stairs.

“We were just imagining and thinking the weirdest things and trying to create a story,” Sanchez says. “It's been so playful that I actually think I’m connecting more to my creative side.”

“I find her artwork really interesting [...] to represent not just what she sees, but how,” says Nick Wees, who attended Maestres Useche’s talk during her time at Concordia.

The Wandering Eye Project encourages free flowing movement and forces us to question the socially constructed reality surrounding sight.

“[People with residual vision] have this deep world, full of images, as many other people. Why don’t we explore this aesthetic?” Maestres Useche says, pointing to one of her drawn stairs. “Why can’t this stair be a symbol of Montreal? Why do you not identify yourself with the way I see, if you are also a living being?”

This article originally appeared in Volume 45, Issue 7, published January 14, 2025.