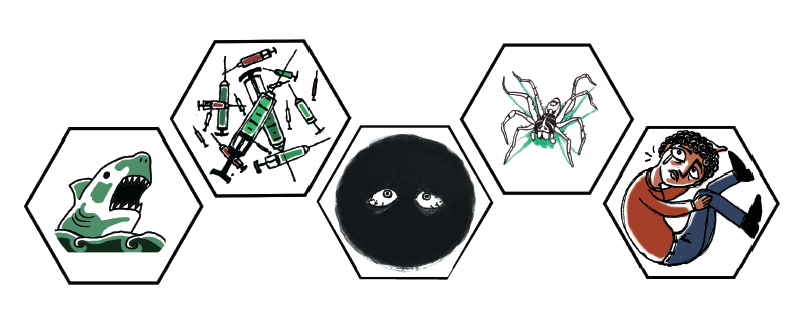

Virtual Fears

From Soldiers to Spiders, Quebec Psychologists Are Pushing the Envelope When It Comes to Using Computers to Fix the Mind.

It’s just after sunset somewhere in Afghanistan.

A group of Canadian Forces recruits, all trained at the Valcartier base about 250 km northeast of Montreal, listen to the day’s final call to prayer blaring in the background when they receive orders to assist a fellow soldier caught in a firefight nearby.

As the soldiers walk into the room where their mission takes them, an explosive goes off in a garbage can.

When the debris settles and the soldiers regain their bearings, the cries of agony make it clear that someone has been injured in the explosion. The room fills with smoke and a pool of blood wells beside an injured soldier.

As the soldiers attempt to stay calm and administer first aid, they try to remember their training.

Fortunately for them, the voices of senior officers and medics are guiding them through the process.

In fact, the soldiers are only a few hours’ drive from their home base of Valcartier, at Université du Québec en Outaouais in Gatineau, QC.

Monitoring them is Dr. Stéphane Bouchard, who watches the 41 volunteers navigate their way through the university’s virtual reality simulator.

Each participant is in full uniform and stands in a room-sized space enclosed by six screens designed to monitor and help stress management in combat. The simulator projects images from a virtual world developed specifically for this exercise.

This simulator, dubbed the Cave Automatic Virtual Environment, or CAVE, is one of six in the world.

The name comes from Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, a parable about using projections of shadows and echoes to enlighten the imprisoned dwellers of a cave.

The CAVE simulator at UQO is designed to help patients manage—and observers help better understand—everything from stress in combat to phobias.

It is the world’s only such simulator dedicated to mental health. In projecting their manufactured images and sounds, virtual reality therapy researchers hope to enlighten the CAVE’s users about the anxiety that imprisons them.

The simulator and simulators like it are part of a form of treatment known as virtual reality therapy and part of a relatively new field of psychology called cyberpsychology, which studies the interactions between people and technology.

VR therapy has only been around for about a decade but may be an incredible boost to the efficiency and effectiveness in the treatment for certain mental conditions.

For example, simulators like Bouchard’s allow users to push their boundaries when it comes to their phobias.

According to his 2012 research, people with phobias often experience extreme levels of anxiety when they first encounter the object of their fear and therefore immediately avoid it at all costs.

However, those anxiety levels typically drop to manageable levels after being exposed to the source for a longer time, which the simulators allow. In other words, it allows patients to learn that the discomfort associated with their phobia subsides eventually.

Geneviève Robillard, the cyberpyschology research coordinator at UQO, says the unit expands the range of possible treatments.

“You can access situations you wouldn’t normally be able to access. Like social anxiety disorder: bringing the person to different places—or people to listen to them—can be a lot of work, but with virtual reality you can basically do anything.”

VR therapy has its downfalls, like any form of therapy. The immersive simulators like the one at UQO, or the therapist who is needed to monitor the cheaper forms of virtual reality, can be costly.

There is also the “cyber sickness” sometimes associated with simulations, as well as the relatively crude and blocky worlds some of the virtual reality simulators employ.

Bouchard founded and directs a network in order to push VR therapy into new places, called the Canadian Cyberpsychology and Anxiety Virtual Reality Network.

However, Robillard also says that meeting with experts of each type of anxiety and the subsequent development of the actual environments can be difficult.

“The funding [for the CCA Virtual Reality Network] has run out and […] it takes a long time because it’s really never been done before,” she said. “The equipment is also extremely expensive,” she added before explaining that they are slowed down by every update in operating systems.

Although the CCA VR Network faces barriers, Bouchard expects to see its first two sets of virtual reality environments soon.

“We will probably see the first around January, for generalized anxiety disorders and [obsessive-compulsive disorder] and the second set—which will be for social anxiety disorder and [post-traumatic stress disorder]—should be ready probably March.

“After that, the CCA will be more active on the scene because we will be collaborating to use these technologies in clinical trials.”

Virtual reality therapy is based on the practices of Cognitive behavioural therapy, which, according to some, is a therapy approach on its way out as it becomes a less and less fashionable approach to therapy.

Robillard contends that it may have lost popularity because where it is most effective, in anxiety-related disorders, patients avoid overcoming their fear directly—which is what CBT compels its patients to do.

“Some patients cannot handle that, or think they can’t [face their fears],” she said. Virtual reality therapy is therefore perhaps a vehicle for those effective but uncomfortable practices “where virtual reality comes in and says, ‘You have to be exposed to your fear,’ which you can do with virtual reality… but it’s not real,” said Robillard.

Even though UQO is the only immersive simulator in the world dedicated to mental health research, in the past half-decade, virtual reality technology has been shared nation-wide with programs like the CCA VR Network, which work to share the virtual reality environments with universities across Quebec and, to a lesser extent, Canada.

Partially as a result of these efforts, Quebec has been a major international leader in virtual reality therapy.

The Institut Philippe-Pinel in Montreal also currently uses virtual reality simulators to research whether it is possible to help sexual predators manage the stimulation they receive from images of a computer-generated avatar of their fixation.

However, in some cases—when the situation is not ‘dangerous’—VR’s actual utility comes into question.

“People often comment, ‘What is the point in using VR to treat spider-phobia for a spider when I can get a real spider?’”

Bouchard explained: “If you get a real spider you need to take care of it and feed it,” adding that “we can now also do things in VR that we not dare do in vivo. Take fear of heights—we would never ask a patient to jump off a cliff in vivo.

“But you can do that in VR, which is actually quite interesting because what the patients […] learn in our lab is that they can jump when they want to. This is something they can’t learn otherwise.”

Both Robillard and Bouchard see a bright future for virtual reality therapy.

“It’s going to happen,” Robillard said emphatically.

“We have already transferred our research to a private clinic […]. Now everyone can use it.”

The clinic, which is in Gatineau, is dedicated to treating phobias with virtual reality therapy.

The ‘In Virtuo’ clinic uses the much cheaper—but, according to Bouchard’s research, equally effective—head-mounted display, which has two screens fitted onto a patient like glasses.

“We are now moving to new disorders (that are more challenging), mobile applications, augmented reality—think schizophrenia, think phantom limb syndrome, think eating disorders. […] There’s a need there for VR.”

_565_352_90.jpg)

TheCube_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)