To That Friend Who Does Too Much

High-Functioning Anxiety

Anxiety is a funny thing. I used to think that I would grow out of it, like when I cut my hair really short and ended up hating it.

I walked through my adolescence believing that how I felt was a symptom of being in high school—never addressing my fears, always internalizing them. I told myself that it would pass; to just keep working hard and repress it. Once high school was over, I reasoned that I would be able to be myself again. I definitely wouldn’t be anxious in university, I told myself.

When I moved halfway across the country, I still found myself with the same heaviness in my core that I had spent the last three years trying to ignore. I started to realize that anxiety had shaped the way I saw the world and affected the way in which I carried myself through it.

I’ve come to understand that I am a high-functioning, very anxious person. There is no “but” between those two things, because they are not mutually exclusive.

We want to believe that because we are still “functioning” on the outside, our anxiety isn’t perceived to be a problem—or even noticeable to other people. You go to school and you manage to get satisfying grades. You work a part-time job, and, realistically, it’s not the worst gig ever. You’re involved, and you love that you are a part of something bigger.

But everyday, I wake up with the same distinct feeling. A tightness in my chest that says “nothing is right,” even though I know that nothing is inherently wrong. My mind and my heart are playing tug-of-war, and I’m just the rope in the middle.

What I’ve learned is that this feeling is a manifestation of fear. A fear that—according to a new study in the journal Current Biology —shapes the way people with anxiety see and live in the world around us. Scientifically speaking, it has to do with the brain’s ability to adapt or reorganize itself by creating new connections. These changes code how we react to stimuli, and the research shows that anxious people are less likely to be able to tell the difference between “safe” stimuli and threatening ones.

For the anxious person, it means that the brain can’t distinguish one emotional situation from another. Even if the new situation is completely irrelevant to the last, if it’s non-threatening or familiar, the end result is usually anxiety.

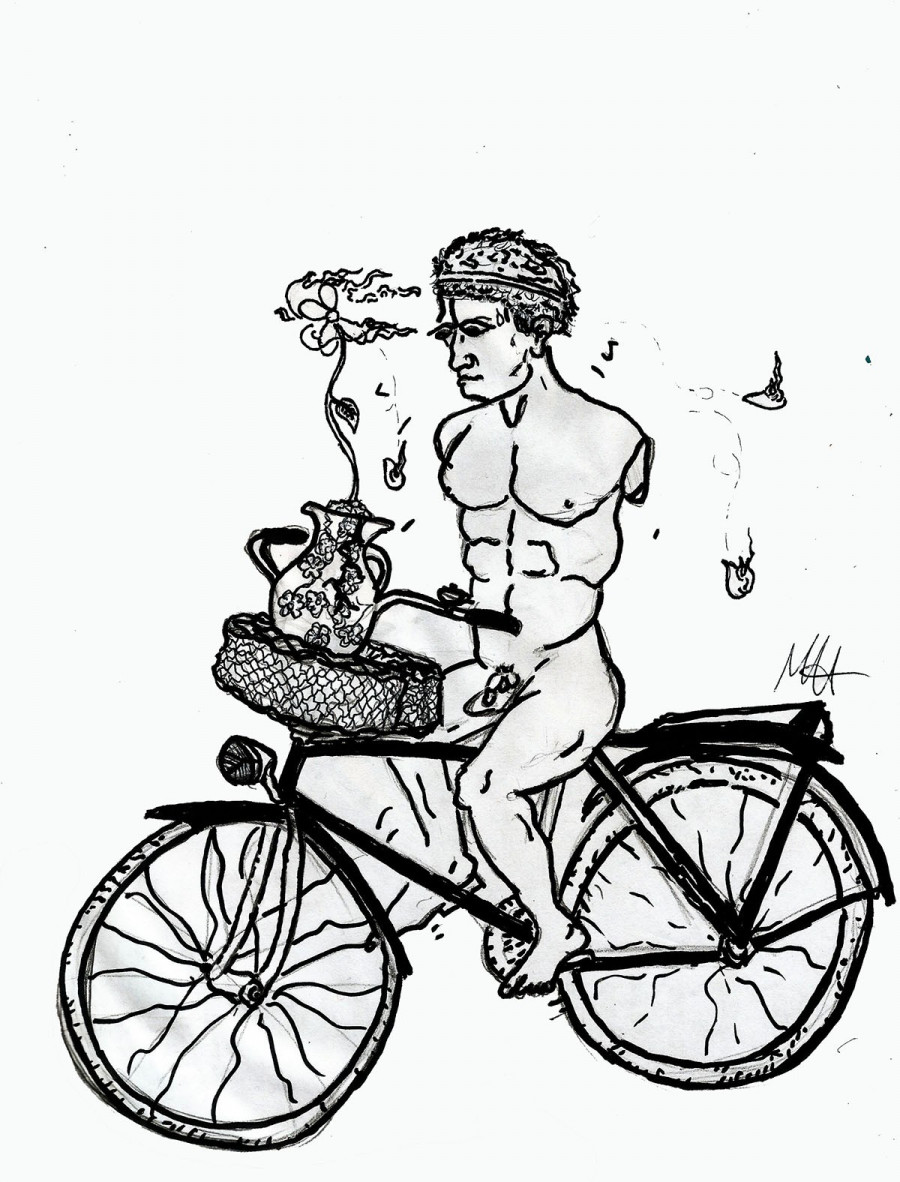

But for someone who has “high-functioning anxiety,” that sense of unease can come from factors that aren’t necessarily obvious. Think: that friend of yours who does too much. (I’m that friend).

Filling my life—and my schedule—with meaningful activities like getting an education, working and saving money, and doing things to further my experience in my field are things that, ultimately, make me pretty happy.

But high-functioning anxiety can look like just that—achievement, busyness, and perfection.

If the things I do in life are water, then I am the cup.

Naturally, I want to do right by the things I love. If I don’t, however, or I feel like I am in some way letting down the people around me—or myself, for that matter—I become overwhelmed by guilt and stress. And it just builds, and builds. Until the anxiety is so unbearable that the metaphorical cup starts to overflow, spilling all of that water over the rim and onto the table until everyone in my life is drenched in the emotional weight of being around me.

That’s how it feels to walk through this world; knowing that I am capable of doing all of things I set my mind to—but also knowing that, soon enough, the world will come crashing down around me like a fucking tsunami.

There came a point this year that I realized that this kind of lifestyle is not sustainable. I can’t do it all—and I know that now. It took falling—like really hard, on my ass—to understand that I had to make changes. Don’t get me wrong, I’m still working on it. I’ve been living with anxiety while trying to balance a busy schedule, an active social life, and trying to keep my apartment clean since last summer. Being on my own has forced me to face up to the fact that I ignored my mental health for way too long, and that aspects of that repression have seeped into literally every aspect of my life.

My roommate once said something during a therapeutic shrooms trip that really struck me. She told me that while I know, deep down, that I am enough, that I am constantly trying to prove my worth to other people. As if to say, “Stick around, please! If you just see me through this, I’ll show you that it was worth it—that I am worth it.”

That’s really the root of my anxiety: that no matter what, or how much, I do, that I won’t be enough.

But I’m working on it, and I know you are, too. Because, if you’re anything like me, there’s no other option than to work on it. It’s what we do; we work and work and work, until we burn ourselves out. And then we start again. It’s a vicious cycle, but I know if we put our minds to it, we can break it.

I’m not going to give you much advice. I could tell you to run a warm bath, buy yourself some flowers, or watch a rom-com that will distract you for at least two hours. But that’s just it—those are distractions.

What I will tell you is this—anxiety is the heart telling you that you’re not on your path. In a way, it’s not a negative thing. It’s a message, rather. If you can follow your heart, the rest will fade away.

You got this.

I am here with you.