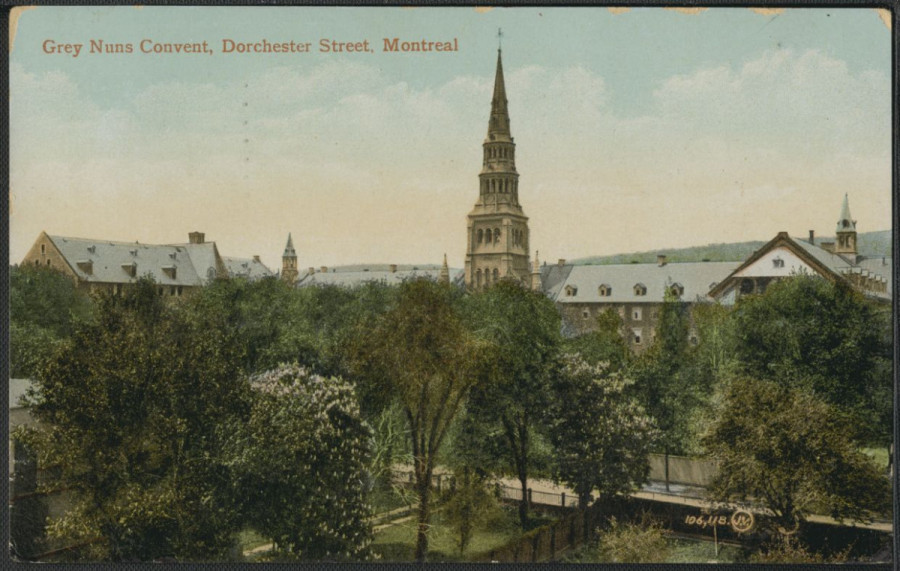

The Ghosts of Grey Nuns

A Haunting History of the Grey Nuns and Their Motherhouse

In 1752, a farmer named Jean-Baptiste Goyer owned a plot of land near the heart of Montreal.

Goyer was quite the negligent farm owner, according to Mark Leslie and Shayna Krishnasamy, authors of Macabre Montreal. He was more interested in spending time at the tavern than tending to his farm.

In May 1752, Goyer announced to those around him he would be taking a trip to Quebec City. At the time, such a trip would have taken a week. While he was supposedly on his voyage, his neighbours, Mr. and Mme. Favre, were brutally murdered. Their bodies were hacked to bits, and their money stolen.

Once word got out of the murders, Goyer began blaming illegal fur traders for the crime. He went as far as buying people rounds of alcohol if they would listen to his theories about the killings. His money never seemed to run out, despite his farm doing so poorly.

Eventually, Goyer was arrested, tortured, confessed to the murders, and sentenced to death. The method of his execution is disputed: some said his body was tied to the back of a carriage and dragged through the streets, and others said he was bound to a wheel, beaten until his bones broke, and left to die. No matter the method, he was buried with a blood-red cross to mark his grave.

In 1969, when Dorchester Blvd., now known as René-Lévesque Blvd., was widened, the cross was moved. Goyer’s body, however, was not. The homicidal farmer’s final resting place likely rests somewhere under the road. Goyer’s plot of land would eventually be transformed into the Motherhouse of the Grey Nuns, now Concordia’s GN building.

For those educated in Quebec, the story of Marie-Marguerite Dufrost de Lajemmerais may conjure memories of high school history class. Born in Varennes in 1701, about half an hour from Montreal, she would go on to be taught by the Ursuline Order in Quebec City between the ages of 11 and 13; she later used her knowledge to educate her siblings.

Around the age of 21, in 1722, Marie-Marguerite married François d’Youville. The marriage led to her involvement in various religious and charitable organizations in the colony.

_900_1340_90.jpg)

The d’Youville family enslaved people. Marcel Trudel, Quebec historian and author of Canada's Forgotten Slaves: Two Hundred Years of Bondage, explained that these people were the d’Youvilles’ “personal property,” the same way livestock were. Trudel recounted how various individuals from the d’Youville family, including her brother Philippe and her father Pierre, owned, bought and sold human beings.

At one point, d’Youville was accused of stealing an enslaved Indigenous person from her step-father, Doctor Timothée Sylvain. She also accepted enslaved people as “gifts” in addition to those she owned.

Trudel recounted how a 1731 notary document noted d’Youville inheriting two slaves from her husband when he died, as well as a Sioux woman and an additional Indigenous woman. Trudel also noted how various hospitals and religious officials owned enslaved people.

During her marriage, d’Youville would have six children, four of whom died in infancy. Her husband, François died in 1730. The two children who survived went on to become priests.

On December 31, 1737, d’Youville secretly founded an association, the Sisters of Charity. The women would take on projects helping the sick and dying, most notably during the smallpox epidemic of 1755 and the Seven Years’ War, which rocked New France.

The sisters would come to be known as the Grey Nuns, in large part because of their grey frocks.

The hospital the nuns worked in, the Hôpital Général in the Old Port, utilised the labour of enslaved people and prisoners. “The Hôpital-Général de Montréal had more slaves than any other women's religious community,” wrote Trudel.

According to William Henry Foster, author of The Captors' Narrative: Catholic Women and Their Puritan Men on the Early American Frontier, “[i]n addition to being confined in cells, the prisoners were subjected to an exhausting schedule of domestic work in other areas of the hospital.”

In 1765, a massive fire consumed the Hôpital Général, spreading over five blocks from Rue du Saint-Sacrement to the hospital. Three people died in the fire, which left 215 families without homes and the Grey Nuns without a hospital.

Following d’Youville’s death in 1771, the Grey Nuns continued their mission in Montreal, as well as out west, giving the godly green light to the expansion of the genocidal, colonial project of Canada.

While the British expanded westward, the Grey Nuns were one of multiple orders working as nurses and teachers in residential schools across so-called Canada. The nuns were active participants in cultural genocide, tasked with what was called “civilizing” Indigenous children. Indigenous children were ripped from their families and forbidden from speaking their languages or participating in their cultural practices.

The Grey Nuns were involved in over a dozen schools. Many survivors have said they had insufficient or rotten food, frequent breakouts of illness and sparse medical care. Other survivors recounted physical and sexual abuse during their confinement in the schools.

In one particularly horrific location, St. Anne’s Indian Residential School in northeastern Ontario, administered by the Grey Nuns, students recounted how an electric chair was used on them throughout the 1950s and 60s. Some were as young as six; the reason the chair was used is disputed. The nuns also used a cat of nine tails, a whip with nine flails, on the children. One survivor, Chris Metatawabin, described the whip as having “the steel things in it that can rip you apart.”

According to the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation in Winnipeg, at least 89 children died at the Holy Angels Indian Residential School in Fort Chipewyan, Alta., another institution where the Grey Nuns worked.

In Montreal, the nuns continued to work in hospitals, caring for the sick and dying. Their commitment to the cause would be tested in the 1840s, as a new wave of immigrants arrived.

As hundreds of Irish immigrants arrived on the shores of Montreal, fleeing the second consecutive year of crop failures during the Great Famine, a typhus outbreak ravaged the community in 1847. That year, 90,000 Irish emigrants sailed for Quebec.

The nuns worked in the fever sheds in Pointe-Saint-Charles, caring for their patients over the course of nearly two years. They also cared for some of the roughly 3,000 orphaned Irish children whose parents died in the journey to Quebec; the Church helped place—not adopt—many of the orphans into settled families. An estimated 6,000 famine refugees would die in the Pointe.

The Grey Nuns lost 13 of their members to typhus as they tended to the sick in the fever sheds. Those nuns, along with hundreds of convent members and others, are buried in the basement of the Motherhouse, just above where students now live.

The only nun whose body was able to leave the Motherhouse’s crypt was d’Youville’s. Her body was disinterred and reburied in Varennes, where she was born. The other nuns’ bodies remain in the crypt for concern of spreading the illnesses they were buried with if they were to be exhumed.

The building’s construction began in December 1868. Its primary undertaker, Victor Bourgeau, became known as the architect of the Grey Nuns. He had worked on three previous projects for them, the chapel for the Hospice St-Joseph, the Refuge Sainte-Brigide and the renovation of a building in Chateauguay. Bourgeau’s vision for the Motherhouse, an H-shaped complex with a chapel at its centre, was never fully realized—the western portion of the structure was never constructed. Bourgeau died in an accident on his way to a meeting with the Grey Nuns in 1888.

Tragedy would be a running theme plaguing the Motherhouse. In the early 1900s, parts of the building were being used as a hospital and orphanage. One floor was occupied by recovering soldiers, and the floor above was occupied by orphaned children.

On Feb. 14, 1918, fire struck the Motherhouse.

By daybreak, over 60 children under the age of four were dead. Soldiers and nuns made it out of the flames, saving dozens of children as firefighters worked to extinguish the blaze.

It was later discovered that the fire was intentionally set by Berthe Courtemanche, who was hired as a nursery worker only six weeks prior. She was tried for the crime, but was deemed unfit to stand trial at the end of 1918. Courtemanche was then transferred to Hôpital Saint-Jean-de-Dieu, a psychiatric asylum where she would die ten years later of pulmonary tuberculosis and cachexia, a wasting syndrome that causes muscle and fat loss.

Following the end of World War II, the Grey Nuns set up various missions in Africa and South America as their numbers started to drop. In 1959, Marguerite d’Youville was beatified, one of the steps in her canonization process, which took place in 1990.

As the nuns’ numbers continued to dwindle, they decided to sell the historic building. In 2004, it was announced that Concordia University would purchase the Motherhouse. Once the purchase was finalized in 2007, the plan for the takeover was supposed to take place in 2022. It is likely that Concordia University knew about the investigation from the 90s and the crimes perpetrated by the Grey Nuns when they bought the building.

However, once the last of the occupants left in 2012, Concordia started renovating early. From 2013 to 2014, the space we know today was created. Initially, the Motherhouse was slated to house the Fine Arts department, but plans were changed. Today, the GN building serves as a student residence, containing beds for 600 students, a reading room, a nursery, a garden and various classrooms.

While the legacy of Marguerite d’Youville and the Grey Nuns is of benevolence and charity, their role in slavery, colonialism and residential schools over the course of centuries proves otherwise. There has been no recognition by the Grey Nuns on their website of their involvement, and they do not seem intent on paying settlements.

The nuns were part of the 2006 Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement, in which they promised to raise $25 million out of $79 million for survivors. However, the Canadian government quietly discharged Catholic entities from the $25 million and legal fees in 2015, meaning survivors may never receive that money. The Grey Nuns sold the Motherhouse to Concordia for $18 million two years before the settlement agreement.

The Ontario Provincial Police interviewed 700 victims and witnesses involved in the tragedies at St. Anne’s Residential School between 1992 and 1998, one of the schools run by the Grey Nuns. Of the 74 suspects identified, only seven were charged, and five were convicted for their crimes.

On Oct. 20, 2022, The Supreme Court of Canada declined to hear an appeal from a group of Residential School survivors from St. Anne’s to hand over thousands of unreleased documents from the investigation by the OPP.

Based on its current website, Concordia has yet to acknowledge the harm done by the Grey Nuns or their role in residential schools. When reached for comment, Concordia Spokesperson Vannina Maestracci said the university will “be looking at these pages soon in order to revise them.”

As of publication, the university’s website has not been updated.

This article originally appeared in Volume 43, Issue 5, published October 25, 2022.

-9_900_647_90.jpg)

-4_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)