How the institution of slavery built Quebec

An integral piece of the province’s violent history that cannot be denied nor forgotten

Saint-Paul Street is considered Montreal’s oldest road, first paved in 1672. Among the many French colonists who established their homes on the street, more than half of all households owned enslaved Indigenous people.

The class of slave-owning white colonists was comprised of merchants, farmers, the political elite, and members of the Church, immensely contributing to the economic prosperity of the colony.

For more than 200 years, slavery was part of Canada and Quebec’s colonial nation-building. In New France alone, there were over 4,200 slaves from the 17th century until the official abolition of the institution within the British Empire in 1834.

More than half of enslaved people were Indigenous, and one third were Black. Thousands of enslaved people were bought, sold, traded and inherited as private property throughout Canada. Indigenous slaves in what is now Montreal were called ‘panis’ in French, which signified ‘Indigenous slave,’ as a large percentage of them came from the Pawnee Nation located in present-day Nebraska, Oklahoma and Kansas.

The Link sat down with Michael J. LaMonica, a PhD candidate at McGill University whose research focuses on the intersection of law, commerce, and empire in the eighteenth-century French Atlantic, to learn about the origins of slavery in New France.

Prior to colonization, the primary use of enslavement within some Indigenous nations was for prisoners of war, LaMonica explained. “Slavery that existed within Indigenous groups was different,” he said. “They would take people in wars and sometimes make them members of their own nation through this process of fictive kinship.”

McGill history professor Allan Greer, who specializes in colonial North America, early Canada, and the French Atlantic world, explained that when some Indigenous tribes took captives, most were women and children who were exchanged with other groups when forging alliances. “Each side would give the other human beings as tokens of connection,” he said.

By the 1670s, LaMonica explained, the French coureurs-de-bois began venturing into the Great Lakes regions for the fur trade, which they called the Pays d’en Haut. Trade relationships and military alliances between different nations and the French colonists were thus developed. “This is how the first Indigenous slaves made their way into Montreal, through these exchanges,” LaMonica said.

However, the system of enslavement utilized by the French was more dehumanizing, LaMonica said. Many nations had a particular status for their prisoners captured in war, which differed from the way the colonists regarded captured people, he added. The primary difference was the concept of hereditary slavery present in the French system. He explained that the colonists viewed enslaved people more as property than prisoners of war.

The children of those enslaved among different nations were generally accepted into the community as one of their own and did not have the same status as their parents, which was not the case within French ways of governing. “They got transferred from an Indigenous context of captive-taking into a European Atlantic slave system,” said Greer. This distinction laid the groundwork for the colonial institution of slavery in Quebec.

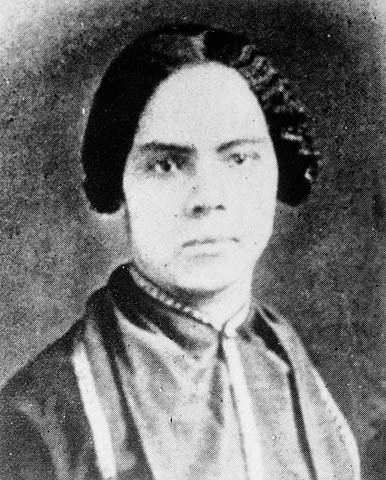

Dr. Charmaine Nelson, art historian and founding director of the Slavery North Initiative, supporting research on the study of Canadian slavery and slavery in the American North, was featured in an episode of the Canadian history podcast Archives & Things in 2022.

She explained that the foundation of a nation is a powerful part of its history, and, foundational to the history of these two empires within Canada—France and Britain—was the use of slavery.

Nelson said that under European owners, slave ownership was permitted by the law, and colonizers strategically organized slavery in a matrilineal fashion so that any child of an enslaved woman at birth automatically became a slave to the owner.

In 1689, Louis XIV instituted the Code Noir in the French colonies, which codified the empowerment of slave owners over the human beings they owned. According to Greer, the code was a regulatory framework for giving slaves religious instruction, baptism, regulations on ownership by Protestant and Jewish people, and so on, but viewed the lives of slaves with such unimportance regardless. “In the French Caribbean, owners had power of life and death over their slaves,” said Greer. “You whip someone to death, you're not going to suffer.”

However, these laws were only officially applicable in the Caribbean colonies because slavery in New France was less developed at that time. This changed in 1709, when intendant Jacques Raudot adopted a colonial law in New France, which legalized the purchase and possession of slaves and reinforced the practice. According to LaMonica, Raudot’s ordinance was passed to clear up ambiguity about owning slaves in the colony. “It was extremely ambiguous to what extent the Code Noir applied in New France,” he said.

New France did not have a large enough market for enslaved Africans, so there were never any boats directly shipping slaves to its ports, Greer explained; “it’s kind of casual trade with colonies.”

However, the colony was complicit in the Transatlantic Slave Trade. As Indigenous slavery was growing, there was simultaneously a higher demand for enslaved Africans. “All of the enslaved Africans who arrived in New France arrived either through the fortified city port of Louisbourg from Martinique or Guadeloupe, or they were smuggled in from the British colonies,” explained LaMonica. “There was contraband between the English colonies and New France.”

After the Conquest of New France by Great Britain in 1763, the enslavement of Indigenous and African people formally continued. “Slavery is explicitly preserved when the colonies turned over to the British,” explained Greer. “There's a clause in the surrender that says French Canadians will be allowed to keep their slaves.”

The number of African slaves increased during British rule. “There was more of a connection to the West Indies, more maritime traffic,” explained LaMonica. Moreover, after the American Revolution, that number grew even larger due to British loyalists fleeing to Quebec and bringing along their slaves.

In her book Slavery, Geography and Empire in Nineteenth-Century Marine Landscapes of Montreal and Jamaica, Nelson explains how, despite ongoing military conflicts and competition over territories in the Americas, the French and the British suspended their ethnic, social, cultural, and religious differences to cooperate for the safety and security of the white plantocracy. Hence, although fierce adversaries, the French and British agreed upon the necessity of the preservation of slavery.

Historians today use two categories of distinction to establish hierarchies of slavery: slave societies and societies with slavery. The former refers to societies that flourished economically through the use of slavery, typically plantation slavery, while the latter indicates societies that don’t necessarily depend on slavery, but have it exist within their borders, LaMonica explained.

The economy of New France did not heavily depend on slavery because there were no plantations like in the Caribbean or in the United States, she argued; slaves were majoritarily seen in domestic settings. “They were mostly employed as domestic servants in a variety of functions, but above all cooks, maids…that sort of thing,” Greer said. This is why New France is considered today to be a society with slavery.

It was only throughout the early 1800s that actions were taken in favour of gradually ending the practice of slavery throughout British North America, thanks in part to the work of abolitionists. Slavery was abolished throughout the British Empire in all its colonies in 1834, 30 years before the United States, making Upper and Lower Canada popular destinations for enslaved people to flee.

Canada’s pride in its role in the history of the Underground Railroad—the network of secret routes in the early 19th century established by abolitionists to help free African American slaves get to free Northern states or Canada—is sourced from its national narrative of being a land of freedom, according to LaMonica. “The fact that slavery existed in New France and after the Conquest doesn't fit comfortably into that narrative,” he added.

“If history makes you feel good, it is not history that you are reading,” said Aly Ndiaye, a Senegalese-Quebecois hip-hop artist also known as Webster. He believes that Quebec chose a narrative that portrays the province as benevolent during the translatlantic slave trade. As an independent historian, activist and lecturer, he wants to democratize access to knowledge about Black history in Quebec.

Ndiaye explained that while the history of the Underground Railroad is important, it must be placed into perspective. Many people who aided the processes of this road were Black. “We forget this to have an image of a white Canada reaching out to Black slaves,” he said.

Ndiaye spoke about what contributed to the marginalization of Afro-Quebecers in the decades that came after abolition. “The mentality that permitted slavery does not disappear as easily as the practice itself,” he said.

He elaborated that the mentality behind slavery is intimately linked to racial superiority, leaving Black people living in Quebec to be viewed not as Quebecers, but “Blacks in Quebec,” even in the 20th century. Consequently, he said, even 60 years later, many Black people remained in domestic work, did not have social mobility, and remained on the margins of society.

_900_791_90.jpg)

Furthermore, Ndiaye explained that because the majority of enslaved Black people who came to Montreal spoke English, this history happened in English, contributing to their alterity. “Due to the linguistic dynamic in Quebec, it is as if Black history in Quebec did not happen because it happened in English,” he said.

Ndiaye believes that history was neglected and then forgotten. “Our method of doing history has always been franco-centered, white-centered, and catholic-centered,” he said. “These are the three elements on which we based ourselves to define Quebec-ness.” For Ndiaye, being excluded from these categories means exclusion from history.

Aeron McHattie, a history librarian at Concordia, finds that the education system in Quebec, specifically at the pre-university level, does not teach children about this particular part of history. As a younger student, “the history I got was standard colonial narrative,” she said.

“Canada's implication in the economic benefit of using unpaid labour bodies was not discussed,” McHattie said. “As someone who grew up in Montreal, it sucks that people don’t talk about it.”

LaMonica also had a similar experience when teaching this history in class. “Students often tell me they had not heard of Indigenous slavery before,” he said. “In university, it’s the first time they're hearing about it.”

Whatever scale of the use of enslaved people in a society is to be spoken about and taught, Greer believes. “There is no such thing as nice slavery,” he said. “To be a slave is to be deprived of any kind of social and family connections, and that was definitely the case in Canada.”

This article originally appeared in Volume 44, Issue 8, published January 16, 2024.