Snapshots of the Subconscious

Lecture at Concordia to Discuss the Surrealist Movement’s Influence on Photography

Rising out of the ashes of the First World War, surrealism is a cultural movement that tapped into Freudian psychoanalysis and sought to revolt against the rational mind’s constraints.

Independent scholar Ian Walker will explore photography’s role in surrealism at the upcoming “Speaking of Photography” lecture series organized by Concordia’s department of art history.

Founded by French author and poet André Breton, the surrealist movement was defined in the 1924 Surrealist Manifesto as a “pure psychic automatism,” a way to express thought processes in the absence of exercised reason and aesthetic and moral concerns.

Surrealism solidified the reputation of notable photographers such as Man Ray, Lee Miller and Henri Cartier-Bresson, but this historical narrative was barely mentioned in books until the 1980s.

“Surrealism is a successor of Dadaism. It was created as a response to the atrocities of the First World War,” said Walker. “There was an awful situation brought about by a civilized and bourgeois society, filled with excessive rationality.”

“Surrealists believed that they could tap into the unconscious [as devised by Freud], to enter into more poetical feelings. They […] became interested by the discoveries of how the unconscious works.”

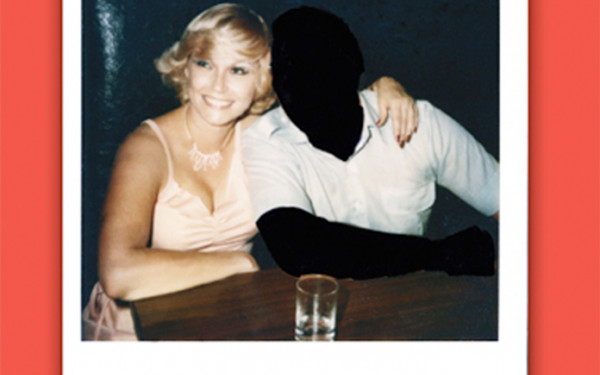

Surrealist photographers managed to overcome the realistic limitations of photography, using it to create images that are symbolic depictions of the unconscious mind’s psychosis, the representations of dreams, taboo sexual fantasies and intoxicated hallucinations. Photography became a medium for surrealism to break down reality.

“Photography was a very realistic tool that wanted to show the surface of things. Surrealism made photography go beyond that surface and showcase what lay beneath,” explained Walker.

“Images became more powerful because they had an underlying meaning. Documentary photographs that caught accidents or coincidences were taken to manipulate and break down the sense of complete reality.”

The movement allowed for implicated artists to experiment in search of new artistic techniques. Photomontage became a popular processing technique that consisted of coupling images together. Multiple exposure, another technique of surrealism, superimposed two or more images to make one.

The Sabbatier solarization effect, discovered by Lee Miller, became a remarkable lighting style that flushed light on a photograph, creating a dramatic effect. These techniques became surrealist photography’s prime focus.

“Man Ray became the pioneer of the surrealist photographic movement,” Walker explained. “He was an American who went to Paris during the 1920s, the heart of surrealism, and picked it up there. […] He experimented and found different and new ways to work with images.”

Though he’s widely remembered as a humanist photographer, the works of Henri Cartier-Bresson were also highly influenced by the principles of surrealist imagery. Cartier-Bresson captured life’s innate absurdity through meticulous geometric compositions and high-contrast monochromes.

“The defining characteristic of surrealist imagery is that there is more than what the eye can see,” Walker said. “There is something there you can’t explain rationally that can mean very different things. The image makes you want to explore further and connect with and play with your imagination.”

Surrealism laid the groundwork for much of today’s photography, as photo manipulation created during the movement influenced future techniques such as the manipulations of Adobe Photoshop. However, the narrative of surrealism in photography was barely mentioned for over 50 years, allowing history to forget about this connection.

“For a long time, surrealism went out of fashion. People forgot about it during the Second World War,” explained Walker.

But changing attitudes during the 1980s resulted in the immediate mass publication of books and exhibitions focusing on the relationship between surrealism and photography.

“People started to focus on it again during the 1980s. I think it’s connected to the fact that people then were interested in abstraction, working with very particular concepts close to surrealism, and people came back to working with their imagination,” said Walker.

“Surrealism is not just about making art, it’s about the whole philosophy of art. It is still a relevant philosophy on how we live and on reality.”

“Speaking of Photography” Series // Ian Walker: The Short, Sharp History of Surrealist Photography // Nov. 14 // 6:30 p.m. // Concordia University, EV-1605 // Free