Sex Ed(itorial): What do we Get Out of Sex?

The Transactional Nature of Sex Can Lead to Unfulfillment

This encounter was not very different from other recent ones—I had swiped right on someone who looked promising on Bumble.

Physically attractive, yes, but whose profile also featured pictures of him engaging in activities that aligned with my interests. We went on a few dates that confirmed compatibility and ended up sleeping together on the fifth, which felt right to me.

I noticed my subconscious mind observing that it also fit within the acceptable timeline of sleeping with someone new who showed longer-term potential. Sex at this point would only further reinforce connection. In the morning, I offered to cook us eggs, but he declined, citing a busy day.

Not long after, he slipped out of my life.

This is not (much) of a pity story, nor is it going to be (much) of a piece commenting on the enduring double standards of the connotations of sex for women. Instead, I want to provide a rationale for why modern romantic relationships have become so difficult to achieve.

Historically, sex was understood as a transformative act (potentially transforming the dynamics of the partnership, in this case through the woman becoming pregnant) and something necessary for a serious relationship. This belief of the transformative potential of sex has, I think, been retained. What’s changed though, is that sex alone fails to hold up to our current demands for relationships. In its failure, the relationship will become casual or end outright.

In the past, in Judeo-Christian society, heterosexual romantic relationship were the obligatory norm, and had expectations for both genders.

Women were to maintain the domestic sphere, and men were to bring home the paycheck. This so-called happy and stable unit was to pump out children, and this was the point of physical intimacy, as dictated by the Church.

Two major shifts in our understanding of relationships have occurred since then, aided by feminism and the sex positivity movement. Relationships are now brokered with the expectation that your partner can better you in your chosen life path, and premarital sex is usually destigmatized.

What is residual from these gender romantic conventions, problematically, and in a way that conflicts with sex positivity, are the norms guiding romantic encounters (i.e. the man should foot the bill, and the woman should hold out before having sex).

Another residual aspect of this way of viewing sex is the conviction that sex is transformative, which derives from the historic weight of the act, representing necessarily both sanctified conception and commitment.

Historically, sex was more connoted with pregnancy than it perhaps is now in our society, and therefore had more economic importance, with the child being the signifier for the household’s wealth. The economic significance of the coupling also was arranged based on the understanding that each person brought specific gendered abilities to the family sphere. The act of sex, in this partnership, would authenticate the relationship and both the parties in their predestined roles.

Now, relationships are less and less commonly brokered to achieve material wellbeing and procreation. Instead, we desire that our relationships further us in our self-growth, likely due to the strains placed on individuals to be high-achieving. This concept is iterated by the work on this subject by Eli Finkel, who in The All or Nothing Marriage also describes our current expectations for our romantic partners to enhance us, so that we may continue with our own self-growth effectively.

This all leads back to my point: We hold onto the residual idea that sex is sacred in the traditional sense, stemming from its historic connotations of religious sanctity and economic well-being, or with the intention of initiating a relationship. That relationship would provide economic and social wellbeing through childbirth and securing social status.

However, we’ve combined this belief with our modern views of what we want out of a relationship, namely emotional and intellectual growth. The act of sex (whether it’s performed one or ten dates in with someone you feel excited about) therefore becomes weighted with its ability to enable immediate emotional and intellectual transformation.

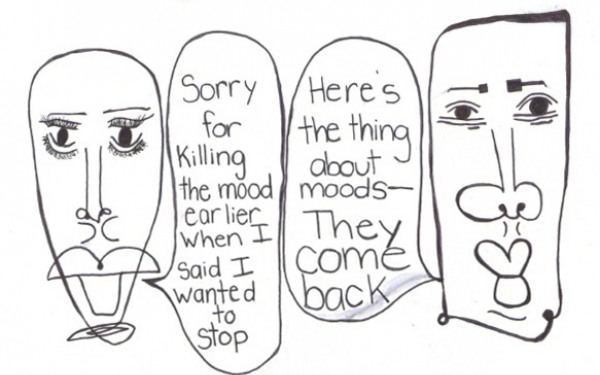

Post-sex, if the relationship doesn’t feel changed for the better with these two goals in mind, it can feel doomed, becoming a casual one or simply ending. Historically, relationships could similarly end if sex didn’t fulfill its then-duty of achieving a child (looking at you, Henry VIII).

So, how can we cobble sex positivity and our modern demand for the deep intimacy that is required for mutual self-growth together, when dating with the intention of seeking a more enduring relationship? Can this be achieved without returning to gendered historic conventions (i.e. “holding out”), which stem from the original motivations and anxieties of physical intimacy, and which I think ultimately impede our new desires of relationships?

I think so, and that two solutions for this current need are a) better communication practices at the get-go of dating someone, to clear the air as to what each person is looking for, and b) a collective understanding of how much work is needed to achieve what we currently desire out of relationships.

During most of history up until the sexual revolution in the twentieth century, a partner’s role was not to encourage your self-development in the same way as today, as your social destiny was almost entirely designated at birth, and you would have been cultivating your gendered abilities up to the moment of marriage when the act of sex would affirm you in your role.

My vision is that putting work into a relationship, regardless of when sex happens, becomes the non-gendered convention of dating, supplanting the reproductive and productive labour that would go into the historic relationship early on (with the advent of a child).

Despite the irony of the fact that romantic relationships can be read as historically working with capitalism to promote exploitation and inequality, the wholeness desired from such partnerships now also symbolizes the holism, the total self-actualization that I think we are wanting to create and witness in our communities.

While sex alone can be enhancing and stabilizing, I am going to stake a claim that reclaiming the romantic relationship is radical in that it refuses the transactional quality that pervades relations in our modern capitalist era.

We want to be high-achieving for our causes, places, and people, instead of only for ourselves. Enduring might be the only way to develop enhancing relationships, and this commitment might just be the basis for developing and transforming ourselves and our individual labours for the collective good.

_600_832_s.png)