PHI Centre presents first AI exhibition with Coded Dreams

The PHI Centre’s exhibition is certainly of its time, but more of an evasive daydream than anything concrete

On Oct. 9, the PHI Centre unveiled Coded Dreams, its new exhibition focused on oneiric, interactive storytelling. It’s also the first show at the PHI Centre fully dedicated to AI.

“We felt the timing was perfect,” said Myriam Achard, the centre’s chief of media relations.

“People ask questions about artificial intelligence. We’re already feeling a strong interest from the public. Tomorrow, for example, we are holding a panel with the artists, and we are nearly at full capacity. For a panel like this, it’s quite rare.”

At the heart of the show are two pieces―Tulpamancer and The Golden Key―by New York artist duo Marc Da Costa and Matthew Niederhauser, built by their associate studio Onassis ONX.

Tulpamancer is a machine-learning virtual reality (VR) installation that explores visitors’ memories. Visitors are guided to Tulpa, a computer named after the paranormal spirits in Tibetan Buddhist mythology, created entirely from the thoughts of other beings. Tulpa prompts visitors to describe various core memories. Then, the visitor slips on a headset to catch a VR audiovisual generation of these memories.

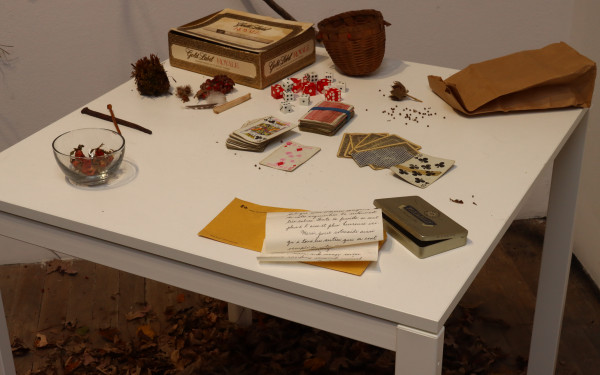

Unlike Tulpamancer, The Golden Key is a communal experience. At this three-projection installation, visitors step up to computer consoles and type in story elements. These elements are then generated into folktale visuals using ChatGPT and open-source, text-to-image, generative AI tool Stable Diffusion, then projected onto surrounding walls.

Da Costa and Niederhauser’s work comments on the increasing integration of AI in our lives.

“[This show] can create contexts that are perhaps different from what we’re reading in the newspaper about either apocalyptic or utopian possibilities of [AI], thereby presenting new ways for people to think about [AI] and to form opinions and ideas,” Niederhauser said.

Da Costa compares some audience reactions to AI art to that of the mythical Lumière brothers’ “Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat.” The 1896 50-second film featured a train speeding towards the camera, which terrified audiences who felt the train was coming out of the screen towards them.

“When people saw this stuff for the first time they really freaked out, like is this train going to hit us?” Da Costa said. “With [AI], it’s still not part of our everyday life, so there is a little bit of technological wonder, even if we are digital natives.”

Still, Da Costa would not describe their work as AI art.

“I would prefer to frame [them] as speculative pieces,” Da Costa said. “Sometimes you see art and works that are very focused on tools and technology. For us, we’re much more interested in asking bigger questions about living in a world with artificial narratives, with things that present as human but have no empathy. AI opens up new creative possibilities to explore.”

The specific nature of these new creative possibilities remains unclear.

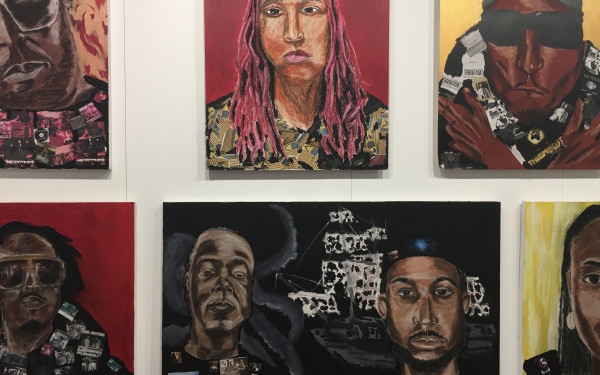

Those who have used ChatGPT before will recognize its fluffy, distant prose. The swoopy, half-formed humanoid faces, animals and trees are recognizable Stable Diffusion graphics—you can make them yourself, in your browser.

Even the worldbuilding of the exhibition—retro green text on black screens in Tulpamancer and the psychotherapist-meets-chatbot setup—leans on longstanding clichés of the tech imaginary. At the same time, Coded Dreams’ gauziness obfuscates the need to comment on more risqué AI ethics concerns. One such concern is the fact that the AI models used are trained on enormous image and text databases, some scraped without the permission of their creators.

So yes, this show has brought AI to the PHI Centre, but is it enough?

Coded Dreams runs until Jan. 12, 2025.