Perspectives on immigration from South Asian mothers

South Asian mothers look back on their experiences immigrating to Montreal

When Primrose Knight immigrated to Canada in August 1990 from Colombo, Sri Lanka, she was escaping a country wrought by civil warfare.

“It was a very tough time because of the bombings happening near my house,” she said. She moved to the capital city of Colombo a mere three months after her mother’s passing in 1989, and was surprised one day by the sudden arrival of her two sisters. Upon arrival, they explained that it was no longer safe to live in their hometown of Jaffna, located at the northern tip of Sri Lanka.

From 1983 until 2009, Sri Lanka faced a devastating war that left the country divided just short of 30 years. The war placed the Sinhalese majority-led government opposite Tamil rebels, leaving a death toll of approximately 100,000.

“I asked, ‘Why have you come here?’ [My sisters] said, ‘We cannot live at home. We are scared,’” Knight said. “From thereon, my brothers were trying to bring me to Canada.”

The immigrant experience varies for a number of reasons, be they in an effort to declare refugee status due to ongoing political conflicts back home, marriage, work, or education.

Having immigrated to Montreal at 28 years old, Knight was eager to start life anew alongside her two brothers, who were already settled in the city. She had her typist abilities to fall back on and was looking forward to furthering her education into a more specialized field of study. However, in an effort to pay back her travel and immigration fees, she was unable to follow through.

“My plan was to study [in an advanced field in university] because I wanted a good job,” Knight said. “But unfortunately, my brother borrowed money from someone to get me here, and the best salary I could get at that time was about $5.30. So, I had to work [...] and earn enough money to pay him back.”

Knight’s reality is not that much different from most immigrant families. Many new arrivals depend on their local ethnic communities, mutual friends, and already-settled relatives to help hasten their immigration processes in an interwoven cycle of support.

“I realize now that I am very sorrowful over the fact that I didn’t get a chance to [complete my] studies, even though my aim was that I would do so when I’d reach Canada.”

The ability to further her academia was limited by the fact that school demands full-time attention—something Knight simply could not commit to due to her impending financial situation at the time.

In essence, immigrating to the western world is sought after in hopes of having what has been depicted in media as a chance at a better life. In most cases, however, the life dreamt of is not what is put on the table, as seen in Knight’s case. Although she now lives a happy life with her husband and two kids in the West Island, the yearning for what could have been remains.

Integrating into a new society comes with its own set of challenges. The language barrier is no exception—and something my mother can attest to herself.

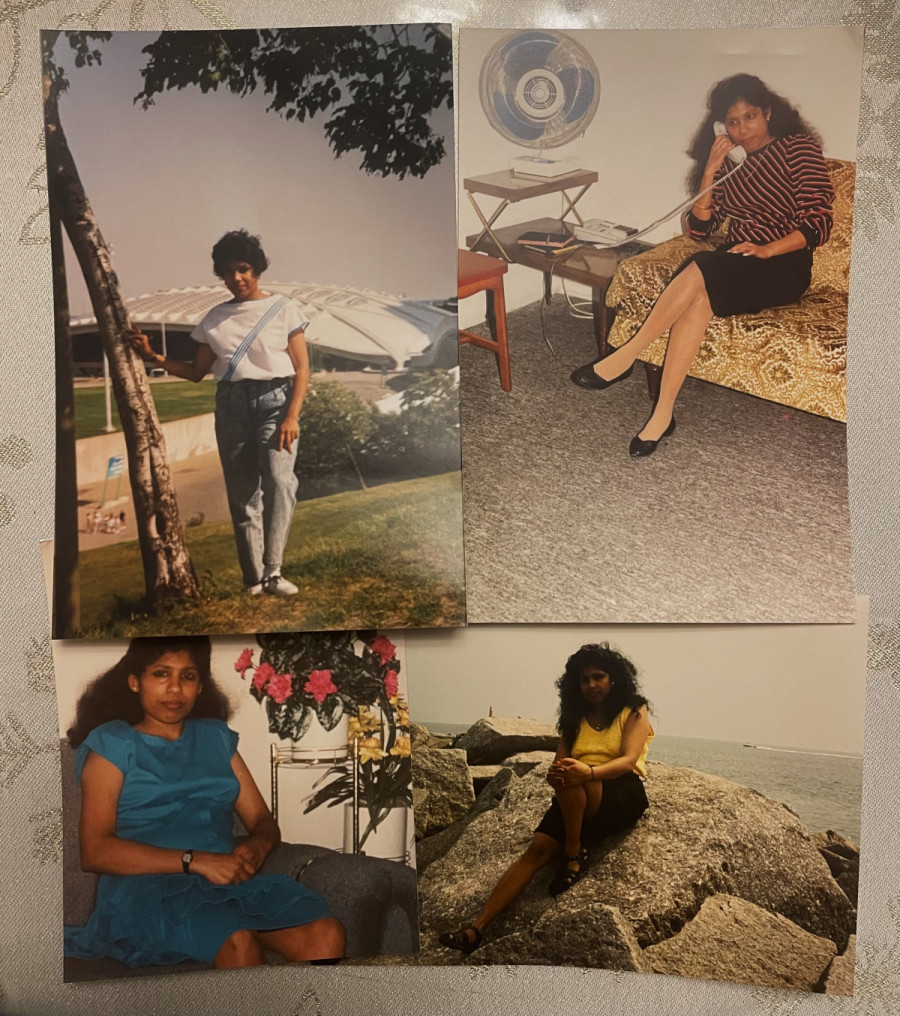

Ophilia Roberts—my mother—immigrated to Canada in May 1998 from Lahore, Pakistan. Her family arranged for her to marry my father, who was already living in Montreal and whom they had come to know through mutual friends and family relations extending between both countries. She was 34 years old.

“It was a smooth transition for me overall because of the way my husband gradually introduced me to the different facets of life here in Quebec,” Roberts said. “I understood learning French as the way to assimilate into society.”

Roberts began attending government-funded French language classes at the Centre William-Hingston in the Park Extension area. She recalls attending class with people from nearly every corner of the world, including Turkish, Afghani, Eastern European, Lebanese, Moroccan, Indian, Bengali, and Ghanaian immigrants, to name a few.

“Leaving some of your closest loved ones without looking back is not an easy decision for anyone.” — Hukamdeep Kaur

Today, she looks back fondly on her days in French school, and often finds herself reminiscing about how far her language skills have come as a Quebec citizen who has been working in retail for more than 15 years.

“Language is a major part of my work, and I have since developed confidence in my ability to speak to the people in and outside of my circle and family,” Roberts added.

Most South Asians arrive in Montreal speaking their native languages and dialects accompanied by a working knowledge of English, the language that is taught in schools throughout South Asia, which was once under British occupation.

This often means that South Asian immigrants usually know more than one language or dialect. Adding on another with the French language is therefore often no easy task for them.

In 1997, Hukamdeep Kaur was 26 when she arrived in Montreal from Moga, a city located in the state of Punjab in India. Like Roberts, she recalls her experience assimilating to the French language.

“I struggled with the language, but my husband was always there with me, which made everything a thousand times easier,” Kaur said. “Difficulties explaining [myself] and understanding other people was the biggest struggle for me. But now, I am much much more comfortable as there is no more language barrier, and [I feel that] I am experienced and have a better understanding of the city.”

The loneliness that follows immigration is one that plagues most immigrant families. The departure from one’s home country affects departees and their loved ones, both in their native and new residences.

“My mother, my brother, and my sister—they are my whole life. Leaving some of your closest loved ones without looking back is not an easy decision for anyone,” Kaur added.

From the very moment they are dropped off at the airport, daily visits turn into phone and video calls as the departee adapts to a new life, void of nearly everyone they’ve ever known. Needless to say, the change of location leaves a dramatic impact.

“I don’t think there was a day I did not cry at first,” said Kaur. “It made it difficult since my husband, who was and still is my best friend, was working every day, and added to the loneliness I could not share with anyone.”

Roberts shared a similar sentiment regarding the homesickness one feels post-immigration. According to her, it is a feeling that one may feel for the rest of their lives because a part of them still lives back home.

“I love my life today, and I am thankful for the opportunities I’ve had and continue to have since immigrating to Canada,” said Roberts. “But I also love and dearly miss my family. It hits you hardest when you hear of relatives passing away, or when major events happen in your family’s lives that you are forced to miss. Communicating with family is what keeps us all going, especially at the very start.”

This article originally appeared in The Sidewalk Issue, published April 5, 2022.