On food, porn and bloody vaginas

A critical exploration of the modern female experience

Mid-afternoon in late November I was dressed all in white and sat in a Persian cafe. My computer was tilted awkwardly and plugged in somewhere halfway across the room. I pulled out Al Hayya: EVERYTHING IS ON THE TABLE and put it down, on the table, where everything is. I took a sip of my friend’s coffee and felt distinctly that blood had begun to drip from my vagina.

“I’m sorry to bother you,” I said to the girls beside me. “But do you have a tampon?”

Indeed they did. Tampon in hand and in plain sight, I marched to the bathroom, inserted it, and marched back with less haste to where everything is.

An elderly blonde lady appeared to save me from my computer’s blank document. “What is this?” she asked, one manicured finger on the cover of Al Hayya.

“Oh,” I said. “It’s bilingual.” I smiled widely in atonement for my shitty response.

Al Hayya is more than bilingual. It is a platform that publishes content on the interests of women in the context of South West Asia and North Africa. The third issue is dedicated to the “infinite ways that food and feminism intersect.”

Food, feminism and femininity converge both outside and within the physical body. When food is considered at face value (in lieu of actual value), it becomes a caloric entity with dangerous physical properties. This is where diet culture and calorie counting become key in a system meant to control women mentally, diminish women physically, and capitalize on body insecurity.

“As a queer feminist Arab woman with a psychological specialty in eating disorders, my lifelong struggle to accept my body has felt like a betrayal to my queer and feminist community,” writes Dr. Rayane Chami in Al Hayya, in an embodied response to a world that objectifies women’s bodies.

Here begs a question―in the eyes of the patriarchy, are women human?

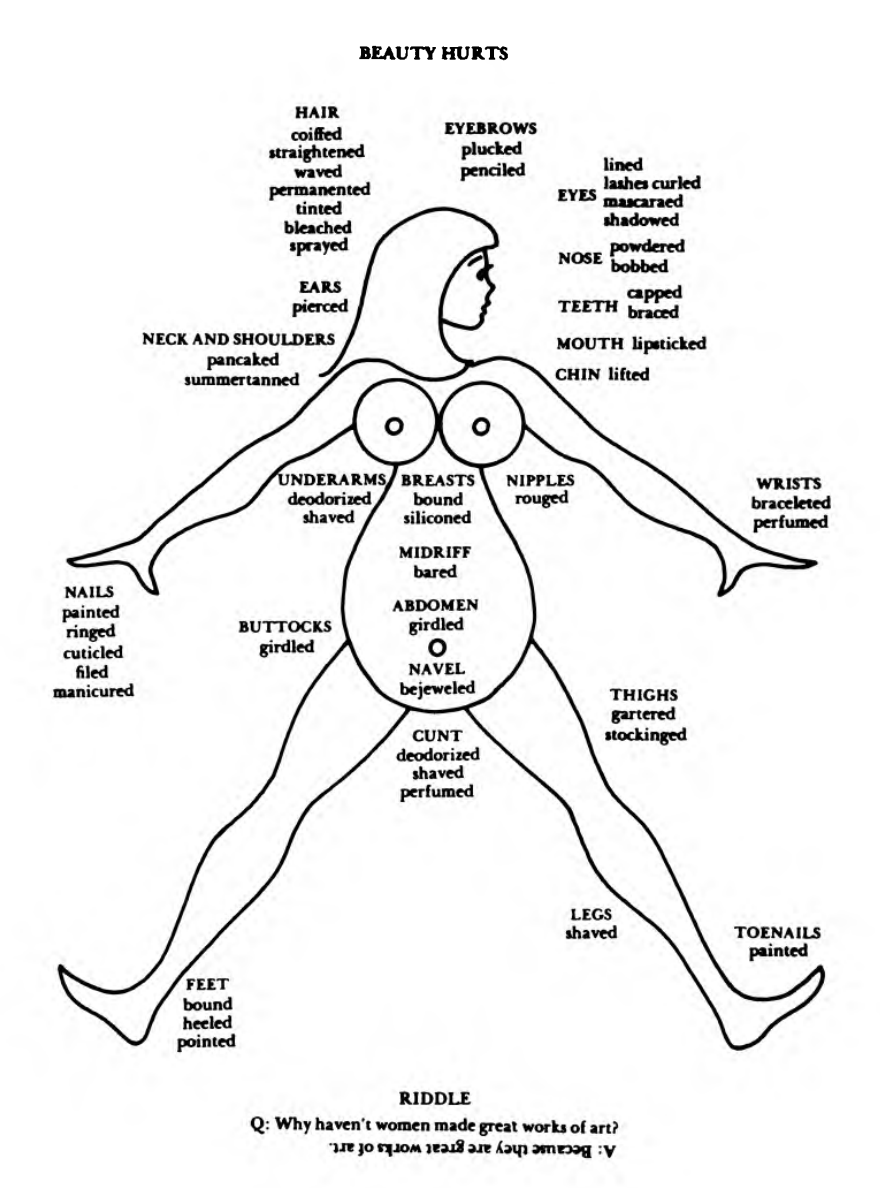

"Woman is not born; she is made,” writes the late radical feminist Andrea Dworkin in the 1981 book Pornography: Men Possessing Women. “In the making, her humanity is destroyed. She becomes symbol of this, symbol of that […] but she never becomes herself because it is forbidden for her to do so. No act of hers can overturn the way in which she is consistently perceived: as some sort of thing. No sense of her own purpose can supersede, finally, the male’s sense of her purpose: to be that thing that enables him to experience raw phallic power.”

It becomes clear that too easily, a woman's body as a “thing” paves way to woman as a “thing.”

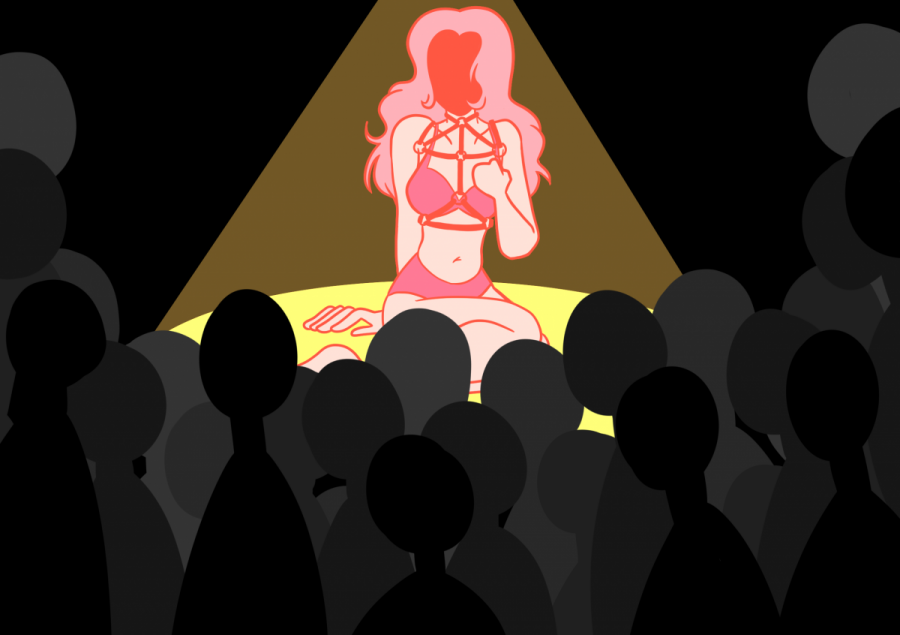

The arrival of the internet and the introduction of the smartphone has perhaps smoothened this path, by providing means to remotely, detachedly, easily and anonymously view women’s bodies in objectifying and pornographic ways.

When pornography is experienced before physical intimacy is, it becomes a psychological training ground for sexuality. Somewhere therein lies the responsibility to teach that fantasy is not to be conflated with reality.

In “Talking to My Students About Porn,” Amia Srinivasan reflects on pornography and the sexual imagination. “The psyches of my students are products of pornography,” she writes. “In them, the warnings of the anti-porn feminists seem to have been belatedly realized: sex for my students is what porn says it is.”

Criticism of porn generally takes two forms: the argument that it is fundamentally abusive in its production (as a coercive industry run by men); and the argument that, no matter its production, it is damaging in its societal effects, promoting a grossly unhealthy image of women, sexualizing violence and distorting young people's sexual education.

Perhaps the danger is that porn not only depicts female subordination, but actualizes it.

On the other hand, there is much to be said on the jouissance of bondage, discipline, dominance, submission, sadism and masochism (BDSM) in all their complexities, pain and pleasure included.

Here arises the psychological and physical dissonance of the self-understood feminists who crave (male) sexual domination. This dissonance can be perceived alongside Chami’s body dissatisfaction and the consequent self-described sense of “betrayal” to her queer and feminist rational ideologies.

Those unfamiliar with dominant/submissive dynamics may view such arrangements as misogynistic or explicitly abusive. Those familiar may find them fulfilling and intensely sexy. In truth, a (submissive) woman’s participation in BDSM is not inherently anti-feminist, nor is it necessarily empowering.

The most basic component of BDSM is consent. Following consent is a relationship built on trust and vulnerability. Perhaps the issue is that porn cannot portray these aspects convincingly, and what is left is the bare bones of violence and oppressive power dynamics under the pretext of kink.

Femininity as an extension of gender is a social construct imposed on the female body. Porn most often portrays the feminine as the submissive. Perhaps the broader danger is that where porn fails to show and/or teach consent, trust and vulnerability in tandem with dominance, submission and sadomasochism, (female) submission is conflated with (female) subordination. And so dominance is conflated with aggressive and/or nonconsensual initiation of sexual interaction.

“There may be salutary possibilities in sexual objectification,” writes Srinivasan. “The authority on what sex is, and could become, lies within [people].”

The penis is a blunt instrument unless unaroused. The vagina is sexy unless bleeding. The female form is a great work of art. The authority on what “woman” is, and could become, lies within people.

This article originally appeared in Volume 44, Issue 9, published January 30, 2024.

_600_375_s_c1.png)

_600_375_s_c1.png)