Nice Tat, Bro

Thinking About Inking in a Cultural Context

I always wanted a tattoo for the sake of it, as a kind of rite of passage on my journey to becoming more me.

But—partly because of what I considered the shallowness of my desire, partly because of laziness—I never followed through.

At 16, it was Frank Zappa with his middle finger wedged high up in his nose. My friends more or less told me to stand in the corner and stay there until I learned to keep such ideas to myself. Whatever, I didn’t know Zappa’s work anyway.

At 18, it was a big black phoenix on the inner part of my forearm. The tattoo artist man told me you don’t walk in for something like that half an hour before closing. Whatever, man, I kind of wanted a peacock anyway.

At 20, it was some henna-style thing my friend designed. Whatever, I don’t even remember it.

In his article “If Tattoos Could Talk,” published in Psychology Today, Dr. Kirby Farrell, a professor studying human behaviour, explains the social and personal significance of tattoos. He says that the tattoo, as a symbol and practice, has power.

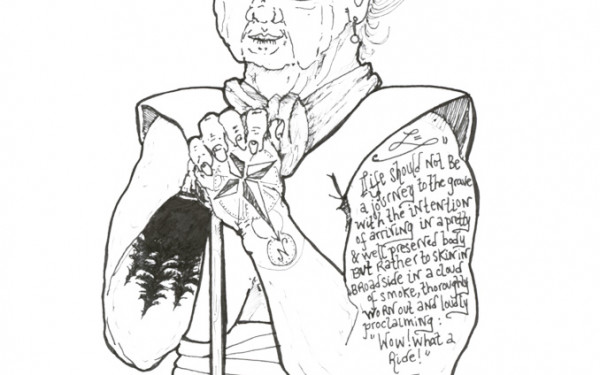

“The tattoo implies you’re in an eternal present, willing to change your body permanently, not worried that the image will eventually become an embarrassing cliché or a maze of wrinkles on grandma’s tired skin,” he writes. Basically, YOLO.

Mimi Santiago, whose real name she asked to withhold, got her first tattoo five years ago. She was 17. Now, the script which reads “Beauty is Beast” and runs down her right ribs, seems too simple.

“I do still love it, [but] I want to add more to it. Maybe add a peacock or a couple of hummingbirds,” she said.

The act of getting a tattoo was once counter-cultural, a tangible expression of non-conformity. They were associated with sailors, with rebels, with jailbirds and with bikers.

Today, according to a 2010 study by the PEW Research Centre, 38 per cent of millennials—people currently 18 to 29 years old—claim to have at least one tattoo.

“Tattoos spotlight the individual but also signify membership in the group of similarly marked folks,” says Farrell. A tattoo, then, is simultaneously a mark of one’s individuality and one’s like-mindedness.

In conducting my research for this piece, I’ve found that it’s not uncommon for the tattooed, like Santiago, to express a desire to alter or add to an existing tattoo.

“It’s really quite common for someone to get another tattoo after the [first]. That’s why [most] people that have tattoos have a bunch—it’s not because they wanted to have all of them, but they add up one by one,” said Mark Kelvin Libario, a part-time finance student at the John Molson School of Business.

Libario got his first tattoo (a small tribal dragon on the right side of his chest) in 2010, and has added to it twice, expanding to his shoulders in 2013, and to his back the following year.

If one tattoo is, as per Farrell, an affirmation of the eternal present, subsequent ones are perhaps reminders that indeed, you are still seizing the day, you beautiful beasts, you.