My F-Words: From Fear to Faith

How I Learned Not to Be Afraid of the Dark

I remember one Thursday, my teacher came in her usual grey abaya, a long dress that accompanies a traditional veil.

She smiled at us, as she always did, and set down the radio she was carrying. “Today we’ll listen to a story,” she said.

She pressed play, and the beginning of my tremendous fear of Islam began. The voice from the radio was low, thick, and melodic—very much like the narration of a horror movie. The contents of the story are a bit hazy in my mind, but I still remember one bit where Hassan, a young boy, disobeyed his parents. Consequently, the Angel of Death came to suck his soul out of his toes, slowly and painfully, as punishment.

To be honest, looking back, I don’t even know if the story was the right one or if my teacher made it up to scare us into listening to her.

I was born and raised in Foz do Iguaçu, a small town in Brazil. My Lebanese parents wanted me to learn Arabic, so they put me in an Islamic school. It was also a great way, they thought, to become more acquainted with “my religion.”

The truth is, and this doesn’t just encompass Islamic schools, religiously driven schools should not be in charge of teaching kids. What I’ve learned in my journey from ignorance, to fear, to love, is that faith cannot be taught.

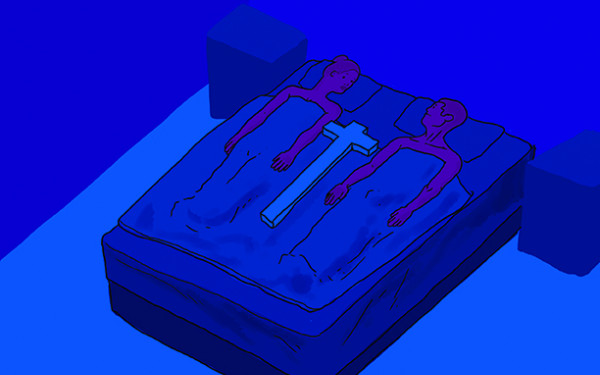

To be honest, it’s not easy to write about this. I still feel a little voice in the back of my head telling me not to risk it, because what if it’s true, and if I don’t obey, the Angel of Death will come suck my soul out of my toes? My 21-year-old self still does not sleep uncovered.

I moved to Lebanon when I was 12 and that was when I started understanding the basis of my fears and where this constant alertness came from. Even though I lived in Brazil, I was part of a small community and wasn’t as exposed to other realities.

When I went to Lebanon, there was such a clash of religions, sects, and things I had never heard of before. I was so confused. That’s when I started reading and asking questions—but never out loud. In a way, I was scared God would hear me, decide I’m a bad person, and send the Angel of Death my way.

At around 14, I told myself that I do not believe in God. Why would I? I didn’t agree with everything the Qur’an was telling me. I thought it was bullshit that there were three Abrahamic religions, that they agreed on almost nothing, and even more absurd was all the sects within these religions. In addition to all that, politics seemed to always come hand-in-hand with religion.

To me, it was simple: If there was one God, why all the division?

I hated the entire construct of religion. I hated how there were designated men telling me what to do, and how everyone just listened. I never understood how in a world where women’s rights are fought for, women listened to those men unconditionally. The whole system frustrated me. Wasn’t religion supposed to be between you and that God?

When I was 17, I met my partner, Rody, who ended up becoming a genuine source of faith. He believed in God and in a lot of the things the Qur’an said, but agreed with some of my frustrations, too. That little part of him agreeing with me was different from what I was used to—”it’s this way because that’s what the Qur’an says,” or “that’s what the Bible says,” or “Because it is.” I felt validated and not alone, and that maybe I wasn’t a bad person for doubting the way I did.

The term deist was introduced to me, and I thought maybe that’s what I am; I believe in God, but not religion. Shortly after, it was agnostic, and I thought, “Oh, that makes sense.” I had no idea what I believed in, but there was something.

When I was 18, I had moved to Montreal to study, and I decided to take a theology course. My professor, a devout Catholic, described faith and belief in God as falling in love. It’s a moment in time when suddenly you’re unafraid, and you’re so filled with love it’s almost overwhelming. I smiled when I first heard that. It was such a lovely way of looking at it.

During this time, I began to understand that religion isn’t really at fault—it’s people. It’s always been people, the way a large number of us are driven by greed and an insatiable desire for power. Somewhere along history, religion became a power play. Not only the Abrahamic religions, but Paganism, too. It was always taken as far off to a point where it wasn’t personal anymore. Even Buddhism today has been so commercialized I can’t relate to it anymore.

The summer after that class, I went back to Lebanon, and I was really agitated. I felt like I was looking for something, maybe that feeling the professor was talking about. There’s something you should know about me, and that is I’m an incredibly sensitive person. If you feel something and tell me about it, I’m going to feel it right with you. If I’m watching a movie and someone cries, I cry too. If they’re happy, I cry happy tears. You get the point. But for whatever reason, I couldn’t feel what the professor described.

Being back around my family, back with Rody, I put that agitation aside. One night, we were watching Mamma Mia! Here We Go Again, and—spoiler alert—the end scene, in which Lily James, Meryl Streep, and Amanda Seyfried sing “My Love, My Life,” cracked me open. I felt something so strong in my chest as each mother figure was approaching the altar with their respective babies that I genuinely couldn’t describe it. I began sobbing in the middle of the theatre.

I looked over to Rody and I’m pretty sure he was as confused as ever—I cry a lot during movies, but it was never like that. I wondered if this was the feeling the professor had talked about. I felt happy. This is it, I thought. I have faith now.

I thought faith was supposed to not let you feel so alone.

After two years with Rody, and two years in Montreal, something broke in me. My family and I went through some personal problems, and I was living alone in Canada. I went through an incredibly self-destructive run, allowed all the fear disguised as anger to take me over, and jumped straight into a rabbit hole that lasted an entire year.

So much went wrong that year, and whatever faith I thought I had acquired the year before just disappeared. No trace of it.

I thought faith was supposed to not let you feel so alone, I told my window once. Wallowing in loneliness, confused, incredibly angry, I decided to take a semester off and go stay with my family.

The process of healing is slow and really shaky. When you think, “Oh, I’m better now,” every single scar you thought closed decides to bleed again. And you think to yourself, I’ve felt this pain before, so it won’t be as bad this time. But somehow it’s worse. It’s as if today’s pain is just mounted on yesterday’s, and the day before’s.

During that time, I looked at the sky quite a lot, mostly at night. My source of faith wasn’t with me, and my siblings were all younger than me. I didn’t want to burden them. I felt it was my job to make sure they didn’t feel what I was feeling—I just wanted to be their support system. For me, it was just really lonely.

I always loved to paint, and the colours of the night sky was a theme I used often. So I started looking up more often and thinking that maybe I’m going to be okay. I remember thinking how far away the sky was, and that maybe it, too, felt responsible for all of us and didn’t want us to feel the loneliness it was feeling.

One night at a time, I started feeling less lonely. It was very strange, like a deflated balloon slowly getting air back in. Within around three months, this feeling was so big it felt like what you imagined sleeping on a cloud would feel like. I was filled with trust—I have no idea in what, but I trusted that I was going to be OK. I breathed more lightly, I walked more lightly, and things began brightening.

There’s a little bit of magic in the world, and I was starting to see it.

I think that’s where I found my faith. It was a long process of building trust and fighting an ego that thought it knew better. Coming to terms with the fact that I don’t know better and that sometimes what I want isn’t what’s best for me, that was what set my faith in stone.

There’s a saying back home that goes “la takrahu shay’an la’allahu khayran lakum.”

What this means is don’t hate or regret what has happened, because it might just be a blessing. After that endless year of pain, I reached the summer of the next year stronger. I didn’t find a religion to fit me, but I learned to see how much beauty Islam has—within its very name, it says surrender—to surrender to faith, to trust. I learned to see how beautiful people were to put their trust in something Other.

Faith is like a long-term relationship—it’s a process of loving yourself, of forgiving, of trusting, of understanding. It can’t really be taught. It can’t be read. It’s just felt.

Maybe it’s that song that helps you sleep when your head won’t quiet down. Maybe it’s that person who holds your hand when you feel alone, even though you never said anything. Maybe it’s that random nice gesture from a stranger. Faith has become the basis of how I live my life. I have faith in myself, in my family, in Rody, in the universe. Partner that with your hard work, and there’s no need to protect your toes from the Angel of Death.