Photo Essay: A Portrait of How People Pray In Montreal

The heart of Montreal is with its people. We visited their places of worship and learned about the different ways people pray across realities. Faith, prayer, and connection to the divine are all facets shared amongst these communities.

Christianity

Christianity, the largest of the five major faiths, is a religion based on the teachings of Jesus Christ of Nazareth. Spread around the world, practitioners have found different ways to pray and interpret their holy book, the Bible.

This led to many splits, reforms, sects, and branches to emerge. Presbyterianism is one such branch of Christianity that originates from Scotland.

Reverend Joel Coppieters of the Côte-des-Neiges Presbyterian Church explained Presbyterianism has a different approach to other sects of Christianity when it comes to prayer and to Sunday mass.

Coppieters’ role is to facilitate that connection through sermons and teachings between practitioners and God, but he urges that prayer can be done anywhere, at any time.

“Prayer is not something you come to church to do. Prayer is something you do. It’s part of your life with God and my job is not to stand between you and Him,” he explained.

“Our understanding is that, on Sunday, it is only the tip of the iceberg in their spiritual life and in their prayer life. They are doing more at home by praying directly. So what we do on Sunday, for me, is far more modeling,” he said. He sees Sunday mass as a sort of school, where knowledge is shared.

During Sunday mass, Coppieters leads the congregation with prayers based on lessons from the Bible and connect with current events.

While he abstains from dictating how to pray, he offers guidance and inspiration to his congregants.

“Prayer is not something scripted,” he said. “It comes from the heart.”

During mass, practitioners sing with the help of a choir. Coppieters explained that singing is a longstanding tradition in Christian faith. Most songs embody powerful emotions that should not be filtered during prayer.

“In the Old Testament, virtually all of the songs are either someone crying out to God because life is crappy and something is going wrong, or it’s someone saying thank you for helping out,” he said.

“There are moments of very raw emotion in the songs. It suggests that, when you are praying, you are not meant to filter it. God wants to hear where you’re at. He wants to hear you scream and yell.”

“Prayer is my connection to God, it’s when I’m speaking with God,” he added. “We think it goes both ways: that I speak to God, and He speaks to me.”

Hinduism

Every morning and every evening, the priests and practitioners at Shree Ramji temple perform Aarti, a ritual in which light—often by form of candlelight—is offered to one or more of the deities as part of religious worship.

Hinduism is polytheistic. Practitioners worship many gods, or deities, each with different characteristics and personalities.

However, they are all understood to be reincarnations of each other, a part of the overarching Brahman, a supreme soul that reigns over all of life. Brahman is all-inclusive, and encompasses everything in the universe.

At the front of the temple, Hindu deities are on display as statues. Their skin is a faint blue, indicating their connection to the sky and to heaven. Their clothing is changed depending on the time of year.

When devotees enter the temple it is customary—but not necessary—to ring the bell that hangs above their head. The ringing of the bell purifies the space, explained a member of the temple. After the bell is rung, practitioners bow at the stage where there the statues are on display.

“Everybody [bows] differently. Some people on the floor, some on their knees, some bow down,” said Bhavesh Patel, a member of Shree Ramji temple. . “It’s not uniform, it’s not caste driven, it’s not section driven. I guess it matters more person to person,” explained Patel.

Deities are celebrated at different times during the Hindu calendar year. Each Hindu temple is dedicated to a different god; Shree Ramji is dedicated to the god Rama, one of the major deities of the faith.

They sing and pray in Hindi or Sanskrit, chanting in unison towards the Gods.

“We are in a sense, welcoming God into our home, and into His home as well,” Priest Goutam Davd said.

The Aarti ceremony is symbolic of the five elements. Space, wind, fire, water, and earth are all ignited before the deities in a ritual that immerses practitioners in gratitude and in the divine.

“Aarti is a way to speak to God without having a direct conversation,” Patel said.

At the front of the temple, Hindu deities are on display as statues. Their skin is a faint blue, indicating their connection to the sky and to heaven. Their clothing is changed depending on the time of year.

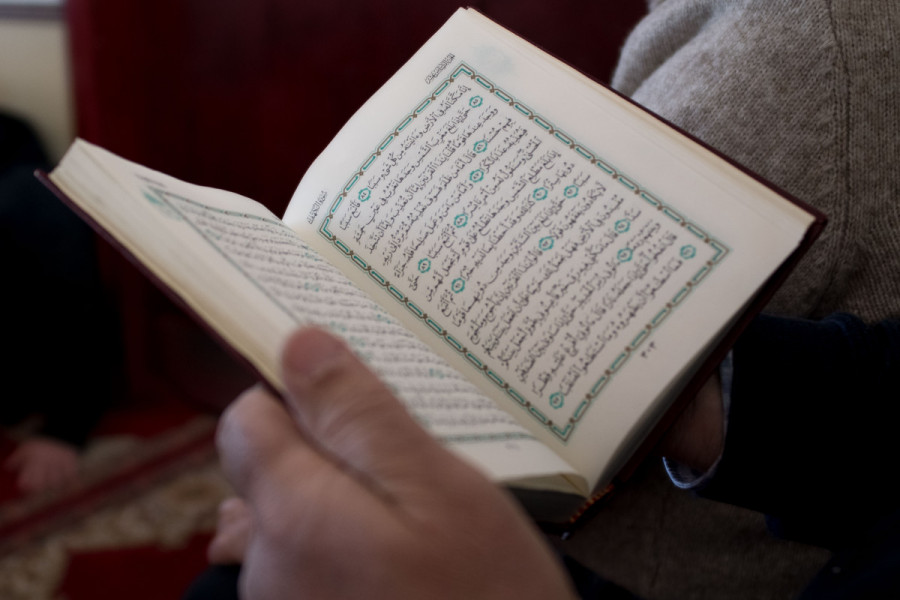

Islam

Salat, or ‘‘prayer’’ in Arabic, is the mandatory ritual Muslims perform five times a day. It is also the second of the Five Pillars of Islam—the five rules every Muslim should follow to lead a fulfilled life.

Prayer is spread at specific times of the day. Al-fajr (at dawn), al-zuhr (at noon), al-’asr (in the late afternoon), al-maghrib (at sunset), and al-’isha (at night) which is performed between sunset and midnight.

While it is encouraged to pray in a mosque, Muslims can pray anywhere. This excludes Salat al-Jumu’ah, or ‘‘the Friday prayer,” a compulsory ritual for every man that takes place in a mosque.

While not obligatory, women may be present—in a different section, separated from men. The Friday prayer is led by the Imam, a man who has extensive knowledge of the Qur’an, their holy book.

“Friday is significant to Islam, because we believe that Friday is the day that God created Earth. It’s the day that God placed Adam and Eve on Earth,” explained Imam Daood Butt, former director of Religious Affairs of Milton, Ontario’s Islamic Community Centre.

Muslims are expected to be clean before presenting themselves to God. To cleanse themselves, they perform the ritual Wudhu, where they wash different parts of their bodies multiple times. This must be performed before every prayer.

The Imam at the mosque leads the prayer with a speech, generally on a topic relevant to the community. Then, practitioners must stand, recite verses from the Qur’an, and bow in the direction of Mecca. This process is done twice.

Butt explained that, for Muslims, Mecca is the house of God. Built by Prophet Ibraham and his son Ismail, it is commanded by God to face its direction—as mentioned in the Qur’an.

“It also signifies unity amongst the entire Muslim religion around the world,” he added. “Anywhere you are, every single Muslim is going to face the same direction. There is no division, which shows that we submit to God and that we do not make our own rules.”

Butt explained that, to him, prayer means submitting to God. “I’m also satisfied because it’s something that brings ease and comfort to my life. You’re leaving your connection with everything else in the world and you’re turning to God in prayer. It’s something divine.”

Judaism

According to the Torah—the Jewish holy scripture—Jewish people are ordered to pray three times a day; morning, afternoon, and night. Prayers are sung in Hebrew, the ancient and holy language belonging to the Jewish people.

Every morning, the prayer service starts with gratitude and is led by a clergyman, explained Cantor Adam Stotland of the Shaare Zion Congregation, a synagogue in Côte Saint-Luc.

“It’s about thanking God for the things that we all take for granted every day,” he said. “From waking up in the morning, for having our brains and our eyesight and being to stand up and to do all the functions that we do every day.”

The Torah is read three times a week, with passages selected according to the Jewish calendar year.

Every morning, practitioners sing the ‘‘Shema Yisrael,’’ a prayer that is “best known to encapsulate all of Jewish faith,” explained Cantor Stotland. In English, the prayer translates to ‘‘The Lord our God, our God is one.’’

“[It is] this idea that we’re all connected, and we’re all one,” said Stotland.

During the morning services, practitioners pray by reading and singing along in their Siddur, the Jewish prayer book. Wearing prayer shawls, called tallit, both men and women tie black boxes with the scriptures of the Torah onto their arms, the black leather tied around their arms and heads.

A religion more focused on doing, rather than thinking, or feeling, tradition is a vital part of Jewish faith. Each action represents thousands of years of history that have been interpreted from the original Torah, and discussed at length between rabbis.

“I think it’s a huge reason why against all odds, we still have Jewish people 3500 years later,” said Stotland. “It’s not a passive religion—you have to live it.”

The Jewish people, explained Stotland, sanctify everything. “I think that holiness doesn’t have to be this austere thing that happens in a church. Holiness is hanging out with your friends and doing something nice with others,” he said. “It can happen every second of every day.”

“I think that holiness doesn’t have to be this austere thing that happens in a church. Holiness is hanging out with your friends and doing something nice with others. It can happen every second of every day.” — Adam Stotland

Buddhism

“Buddha teachings are like medicine,” said Venerable Geshe La, a Buddhist Monk from Tibet teaching at Manjushri Buddhist Centre in Longueuil. “If the doctor gives you medicine, you need to take it,” he said.

The medicine, he explained, is meditation—a stilling of the mind, meant to pull oneself away from the cycle of negative thoughts and into a blissful state of being.

Practiced through the act of meditation, repeated mantras, and focusing on the gold statue of Buddha erected in the centre of the altar, Buddhism revolves around the teachings of Siddhartha, an ex-nobleman who dedicated his life to overcoming suffering. Siddhartha, who is known as the first Buddha, developed the cure to ending all suffering, known as the Noble Eightfold Path.

The Noble Eightfold Path outlines a way of attaining enlightenment. The right understanding, intention, speech, conduct, means of making a living, mental effort, mindfulness, and concentration, play equal roles in reaching enlightenment.

To some, Buddhism is more than a religion. It is considered a philosophy—a way to live that follows the Noble Eightfold Path and the Four Noble Truths.

An untamed mind, explained the La, becomes easily attached to negative thoughts and feelings that will inevitably cause suffering.

Monks, explained the Venerable, are like nurses; doting out the teachings of the Buddha for practitioners.

The Centre is adorned with colourful offerings, wax candles, and oil. It is a space where practitioners come to pray, meditate, and to achieve relief from suffering.

Early on a crisp Saturday morning, Buddhist practitioners take a book from the shelf of scriptures. It is translated into both Vietnamese and English from its original Tibetan. Practitioners sit down on soft pillows and begin to chant in unison.

According to La, Buddhists pray three times a day, morning, afternoon, and night, repeating mantras found in the Tibetan Buddhist prayer book.

Attachment is the cause of a negative mind running rampant and untamed, explained Venerable La. By stilling the mind, one is able to let go of the attachment to his thoughts.

All sentient beings have the ability to become enlightened, according to La. It all depends on opportunity, and practice.Through meditation, stilling the mind, one may achieve what is known to be Nirvana, release from suffering and an end to the cycle of reincarnation.

Buddhism is often practiced in tandem with other religions. Like flavours, or textures, what feels right to one may not feel right to another, explained the monk.

“More narrow mind, more problem,” he said. “Too much attachment.”

An open mind, explained the monk, is key to Nirvana.

_900_585_90.jpg)