Montreal Led the Canadian Abortion Rights Movement

A Peoples’ History of Canada Column

If I had a dollar for every time I have overheard “Thank God we’re not American,” I’d be rich.

Given what has recently been happening south of the border, I understand the sentiment. But there’s something troubling with the age-old Canadian tradition of looking down on America—it often makes us complacent and ignorant of our own struggles.

Many Canadians can probably list in great detail the recent alarming news coming out of America. On the subject of women’s rights to an abortion in the U.S., practically everyone knows that Trump signed an executive order cutting foreign aid to organizations that mention abortion. On the other hand, how much do Canadians know about access to abortion in Canada?

The reality is that most of us know very little about Canadian abortion rights and the accessibility issues women still face here. Prince Edward Island announced only last year that abortion services would be performed in the province—previously, none had legally been performed on the island since 1982.

A large part of Canadians also don’t know much about the history behind the pro-choice movement in this country. That needs to change. Canadians must learn about our hard-fought battle for abortion rights so we can better understand and protect its accessibility for generations to come.Prior to 1969, abortions were completely illegal in Canada. Of course, women were still secretly getting the procedure done, but at that point it was only accessible to those who were well off, and there was a high risk of mortality. According to the Pro-Choice Action Network, 4,000 to 6,000 women died in Canada between 1926 and 1947 as a result of shoddy, illegal abortions. It’s worth noting that up until that point, contraception was also illegal.

In 1969, the federal government legalized abortions under certain circumstances. According to this new law, a woman could have access to an abortion at a hospital if a panel of three doctors, known as the Therapeutic Abortion Committee, believed the pregnancy was seriously threatening her physical or psychological wellbeing. In other words, women could only get legal, safe abortions if they were going to die or go crazy as a result of the pregnancy.

Furthermore, the law wasn’t uniformly applied throughout the country and gave wide autonomy to these doctor committees. Despite the government’s orders, some hospitals didn’t even bother creating the panels and chose still not to have abortions. As a result, women still had limited control over their bodies and their access to abortion was entirely at the whim of the committees.

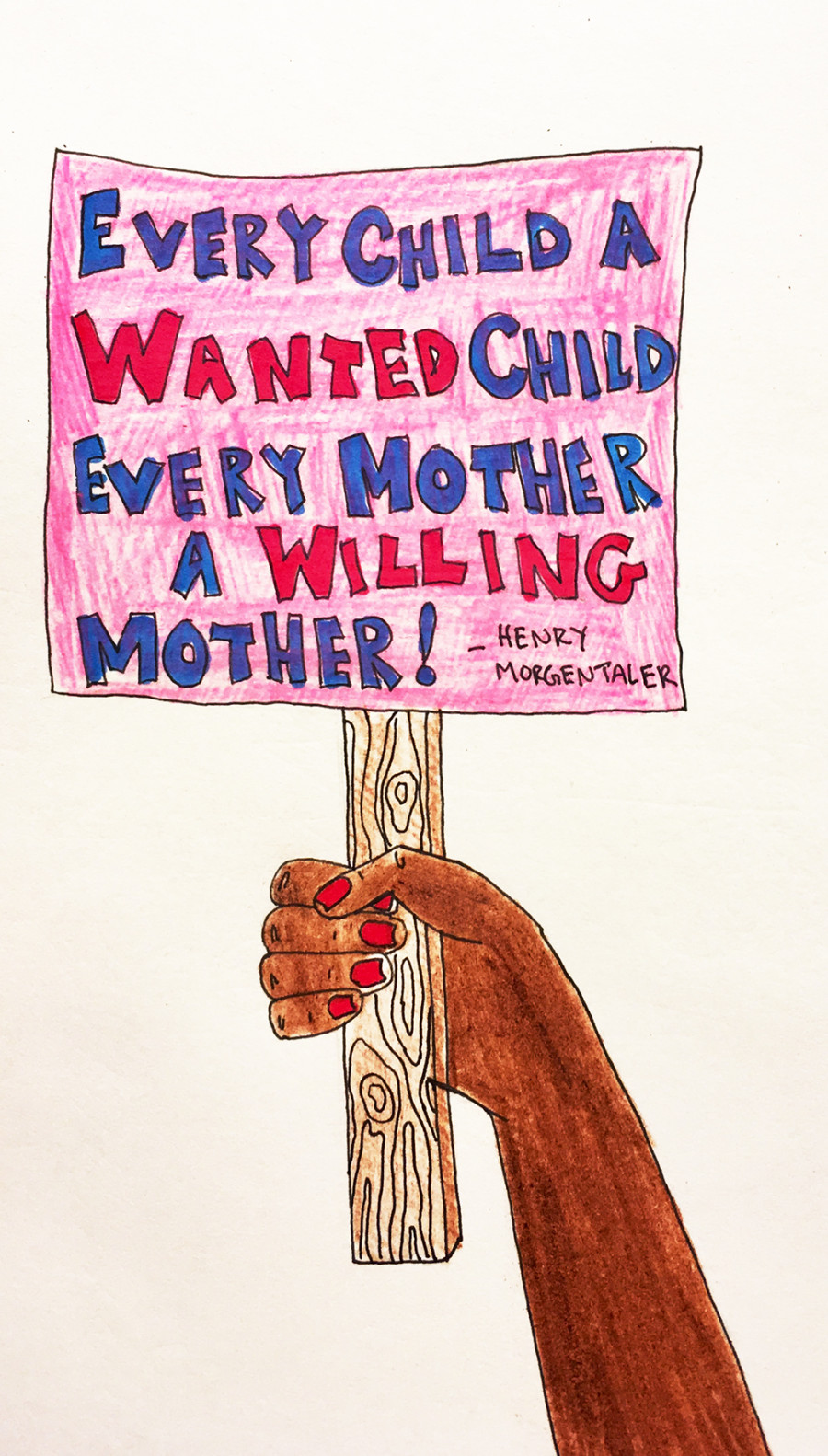

In 1969, Dr. Henry Morgentaler, an abortion rights pioneer, opened the first independent, safe abortion clinic in Canada out of a house in Montreal. This clinic ran in direct defiance of the law created that year, seeing as Dr. Morgentaler performed his procedures on women without consultation from a Therapeutic Abortion Committee.

Dr. Morgentaler was a humanist who unequivocally believed that women deserved autonomy over their own bodies. Although his work is not the defining feature of pro-choice resistance in Canada, he became one of the most important figures within the movement.

In his early life, Morgentaler was a Polish Holocaust survivor whose mother, father and sister were killed by Nazis. The death and destruction he had seen while growing up would haunt him later on, but it also became a motivating force behind his work.

In an interview with The Globe and Mail in 2003, Morgentaler explained that he helped women have children when they could love and take care of them—and believed that kids who lived under those conditions didn’t “grow up to become rapists or murderers” and “will not build concentration camps.” In his view, providing abortions created a more humane, loving and just society—the opposite of what he had lived through in the camps.

Morgentaler immigrated to Montreal in 1950, newly married to his high school sweetheart. In Montreal, he went to medical school at the Université de Montréal, became a doctor, and eventually opened his own private practice. During his early years in the medical field, he saw countless, avoidable deaths of young women due to botched abortions. Over the span of a decade, Morgentaler, who had always been a man of strong convictions, went from advocating for these women’s rights to directly helping them by opening his own abortion clinic.

Dr. Morgentaler developed safe, new abortion techniques and provided his services without judgment. His clinic soon became well known, and served women from across Canada and the U.S. For years, the Montreal police turned a blind eye to Morgentaler’s clinic—and even secretly sent their wives and daughters to visit him for abortions. However, after two and half years of existence, the police felt they could no longer ignore the clinic and it was raided.

This first raid in 1970 set off a series of other police raids and charges against Dr. Morgentaler that would last several years. As defiant as ever, Dr. Morgentaler responded to the charges by openly admitting that he performed abortions and had in fact done around 5,000 safe ones since he had opened his clinic.

He then continued performing these illegal abortions before his trial, and shared a video of himself doing the procedure on national television on Mother’s Day in 1973.

Against all odds, a jury acquitted Morgentaler after his first trial in Montreal. Although a year later, in an unprecedented move, the Court of Appeal reversed the jury acquittal and sentenced Dr. Morgentaler to 18 months in jail without going through a re-trial. This miscarriage of justice is actually no longer allowed by Canadian courts, but in the end Dr. Morgentaler served ten months in Montreal’s Bordeaux jail.

In 1988, the Supreme Court of Canada struck down its abortion law, thereby vindicating Morgentaler, but he didn’t stop then.

On the whole, Morgentaler spent over three decades in the court system fighting for women’s rights to an abortion. In spite of the near constant threat of violence and harassment, Morgentaler also set up abortion clinics throughout Canada, which he oversaw until his death.

Despite all of Morgentaler’s accomplishments, there is more work to be done. If he were still around today, he would undoubtedly agree that we cannot afford to become complacent until reproductive health services are readily and equally accessible to all Canadian women.