Special Issue: Mixed Feelings

Behind the Scenes of a Documentary on Being Multiracial

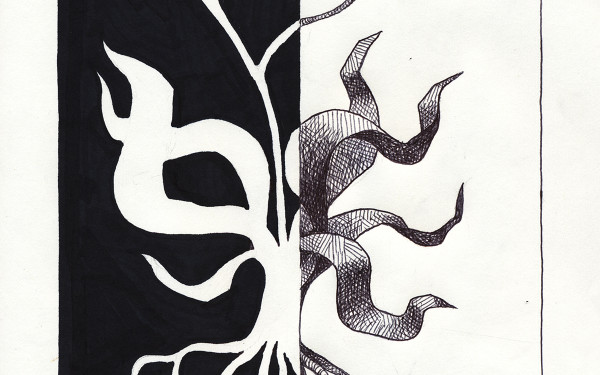

Since last semester, I have been working on a film photography series and a documentary short called Mixed Feelings.

This visual project is concerned with the multiracial experience. It features varying subjects’ unique stories, highlighting their experiences of self-identification coming from differing mixed racial backgrounds and their navigation of a society with overlapping cultural expectations.

This is important to me because I am mixed-race. My mom was born in Montreal and has English, Irish and Scottish heritage, whereas my dad was born in Toronto and has African-American, Jamaican, Bajan, Irish and Indigenous heritage. Since I am not included in the film, I wanted to reflect on my reasons for creating this documentary.

No one else in my video production class was interested in producing non-fiction. No one else was a person of colour. Although these factors might not seem related, I couldn’t help but wonder why this story was so important for me to tell. Then I remembered a statement I heard repeated throughout the Concordia Communication Department, a slogan that gained popularity during the Women’s Liberation Movement: “The personal is political.”

This phrase reminded me that we see the world through the lens of our individual experiences, which intersect with social and political structures. Consequently, through our individual actions we are able to raise awareness and effect change. This pushed me to create the documentary, especially because this topic is also widely ignored in popular culture. I had never felt such a strong need to produce something, especially given the lack of initial intrigue or understanding from my peers. Thankfully, a long-time colleague and friend, Margot McManus, agreed to help me produce the documentary I desperately needed to make.

As a group, mixed-race people are underrepresented within art and mainstream media. This could be for two reasons. First, mixed-race people represent a range of diversity, which makes it more work to represent them properly or understand how they identify. This was probably the biggest lesson that I learned from creating the documentary and interviewing so many people. Each individual’s experience of his or her own cultural identity is unique, and it takes time to understand.

The attempt to thoroughly understand took lengthy interviews, which exhausted both the interviewees and myself. Unpacking a lifetime of explaining backgrounds and experiencing identity crises took an emotional toll on everyone involved in each interview. That being said, it was worth it to be able to represent those individual identities adequately.

I wanted to see if any other mixed-race people could relate in some way or another to my concerns.

The second reason why mixed-race people are often misrepresented stings a little more. It has to do with the systemic racism and microaggressions experienced collectively—rather than individually—for many mixed-race people.

A lot of my interview questions had to do with the issues that I have experienced throughout my life. I wanted to see if any other mixed-race people could relate in some way or another to my concerns. And I found we all shared common experiences and faced similar problems throughout life.

The first issue is the notion of performativity within culture. Being mixed Black and white, at times I would be considered too white for the Black kids and too Black for the white kids. I find culture to be established and practiced in everyday behaviour and language.

So in my case, at times belonging to different cultures, I would find it more convenient to perform one set of cultural expectations over another. This just permitted me to dismiss different parts of myself at different times, denying my identity as a whole.

The second issue involves how people assume your ethnicity or don’t accept the way in which a multiracial person identifies. Mixed-race people need to be allowed space to define themselves as more than just colours or just nationalities. Subjects took around five minutes to explain how they identify culturally.

We need to be given the opportunity and the respect to describe ourselves for however long it takes. It is also important to note that not all mixed-race people may know their entire heritage. As many of my interview subjects also acknowledged: lots of family history, including my own, got lost in colonialism and the Atlantic Slave Trade.

On the other hand, those who are light-skinned or racially ambiguous are often fetishized in the media. These stereotypes rub off in the real world. I would be rich if I had a dollar for every time someone was overly enthused about my tan skin or said I was attractive for a Black girl.

I’m certain there are lots of people who may have never considered how the experience of mixed-race people may differ from those who are not. The ability a person has to ignore some of the issues these people may experience directly relates to that person’s privilege in society.

Though race is a construct, it can affect how we are perceived. I encourage all people to consider this more often. My project partner Margot said something during one of the interviews that summarizes the importance of white people, like herself, acknowledging their privilege.

“If you feel guilty about any of this, you’re simply not doing enough,” she said.

2_900_597_90.jpg)

_900_597_90.jpg)

3_900_597_90.jpg)

_600_832_s.png)