Montreal Universities Keep Philosophy Alive At PhiloPolis

A Recap of Ideas Old and New at Student Symposium

Often left to grapple with the cadavers of academia, philosophy students, professors, and enthusiasts alike gathered to prove that the heart of the discipline is still alive and beating.

This weekend, Montreal was home to PhiloPolis, an annual three-day student organised philosophy symposium. It held over sixty bilingual conferences, workshops, and presentations across the city’s university campuses.

Bookended by discussions of robot overlords and troubling train car reflections, the festival started Friday, Feb. 10 at the Bibliothèque et archives nationales du Québec. There Professor Elsa Dorlin from the Université Paris-VIII in France spoke about the problems pertaining to the feminine body in the face and in defence of violence.

Though the event is no longer held together by a theme, there were familiar messages among many of the talks this weekend.

“I’ve noticed that as well, looking at the program,” says Corrine Lajoie, a masters student at Université de Montreal, presenter, and former organiser of PhiloPolis. “I think it is just a trend that develops, like what is being read at the moment.”

On Feb. 11 one of the main lectures at McGill was given by Professor Nicolas de Warren from the Katholieke Universiteit Leuven in Belgium. Their talk “How Can One Trump Stupidity?” was as explicit about its subject as the title suggests.

De Warren focused on the historical figure of Alkabiades, one of the characters in the Socratic dialogues, whose trappings of charisma and wealth disguise his willed inability to learn.

This, he said, is stupidity. Unlike ignorance, which stunts the prisoners of Plato’s cave, or the sophist’s pretense to knowledge, Alkabiades’ stubbornness towards learning is a political obstruction. An impediment at the centre of an ancient political concept in which the lack of care to the self results in damages to the common good.

The ethical responsibilities of the individual in our current political climate was also one of the ideas found in many of the presentations. De Warren connected the ancient and the contemporary, comparing Alkabiades to Donald Trump.

De Warren suggests that the individual’s stupidity leads to the “collective function of stupidity”: organised systems of intelligence centered on not knowing.

These systems project false issues, such as racialized threats, which only serve to obscure evidence. The fact that more toddlers have killed US citizens with guns than have terrorists from the seven countries under Trump’s travel ban, he said, is held unaccountable.

The following day at UQAM, Lajoie’s presentation addressed the ethical dilemma of power dynamics less explicitly. Her conference “Affective Orientations: Critical Perspectives on the Promise of Happiness” brought into question the political privilege of certain bodies in certain spaces, specifically the extension of racialized, gendered, and emotional bodies within their environments.

“One of the things that is very interesting about PhiloPolis is that in a conference room you have so many different types of people,” Lajoie said Sunday after her discussion. “Where there is a possibility of discussion and exchange that you don’t always get in conventional philosophy conferences.”

As a past organiser, Lajoie explained that the event started as a space for students to present their research. “Sometimes it’s a side project, sometimes it’s a paper that they wrote for school,” she said.

Philopolis is an environment in which students are in control of their own education, and are able to discuss what is relevant and important to them.

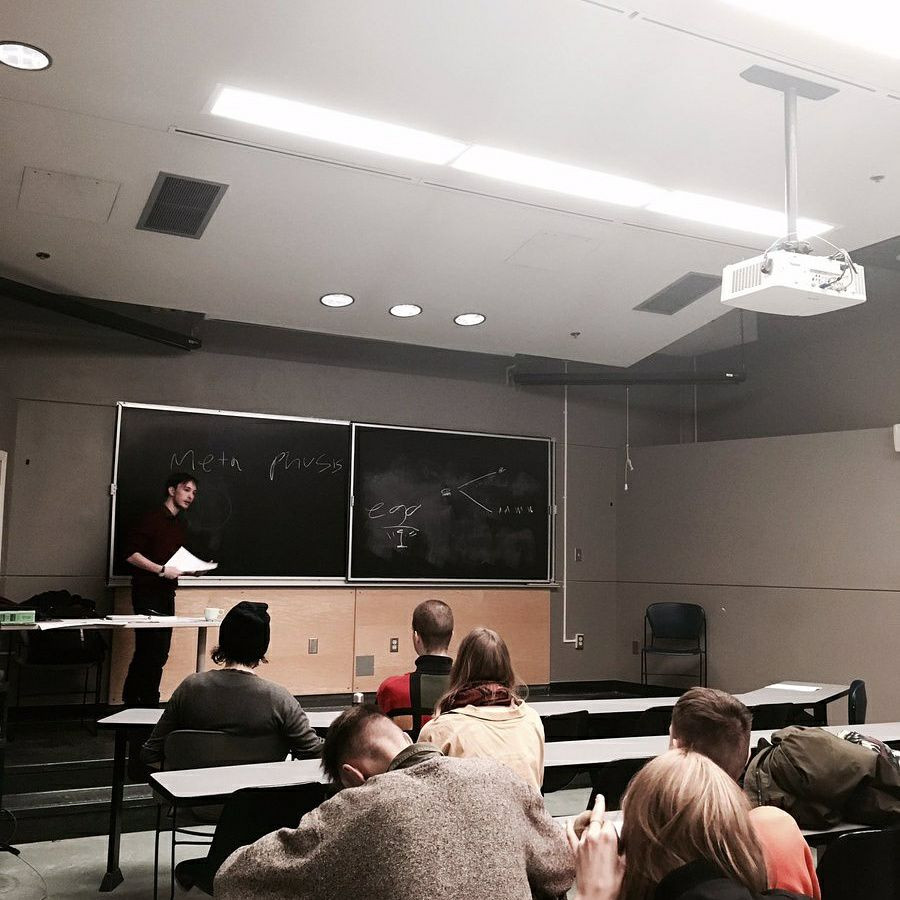

In the case of Emmanuel Cuisinier, a Philosophy and English Literature major at Concordia, watching his professor in class was what inspired him to present. This was his first address at an academic conference.

“Even though I knew the stuff, I redid it, I rethought, I relearned. That’s the kind of educational philosophy I think is beneficial: when the teacher learns with the students.”

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)