Living in Cabot Square

What Life is Like for Montreal’s Homeless People Being Pushed Out

“We have our problems, but we’re not bad,” Gaitan said with pride.

Gaitan is one of the many locals who can be seen hanging out around the Atwater metro, the Montreal Forum and Cabot Square.

Gaitan’s large Saint Bernard used to wait with him in front of Alexis Nihon, all year long, as he sat with a hat on the ground, waiting for commuters to drop off change.

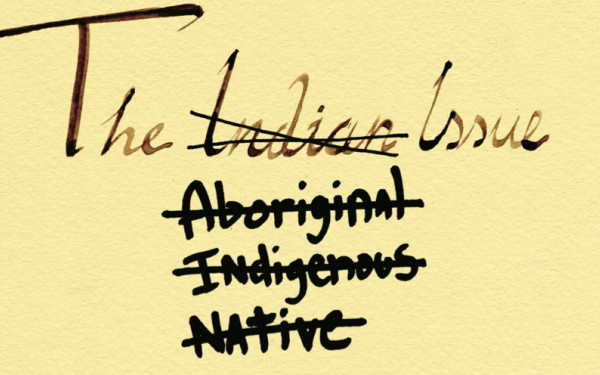

For years the Cabot Square area has been known to be a rough area. Historically it’s been a gathering place for a large homeless population in Montreal, especially those who are First Nations.

In its heyday, Cabot Square was a major hub for transport, being a bus terminal and the western end of the metro when it was first built in 1967. The square is sandwiched between Ste. Catherine St. West and Tupper St., between the Forum and what used to be the Montreal Children’s Hospital, and it sits just across from the Alexis Nihon mall. It still operates as a bus terminal, especially for the night bus network. Recently, the Atwater metro entrance in the square was renovated for $3.3 million.

Mark Shewan works at the Forum on Atwater Ave., and has for the last 17 years doing maintenance shifts during the day. Because of the nature of his job, Shewan has gotten to know many of the homeless people in the area who come into the Forum to use the washrooms and get out of the cold.

Throughout the day, Shewan will go on smoke breaks with his buddies from the maintenance crew and sit across the street in Cabot Square. One by one, different homeless people come up to Shewan to say hello and tell him about what’s been going on in the park. Shewan listens, gives advice and maybe a cigarette, and then returns to his job.

“It’s not all rage and drugs all the time. People think if you’re homeless, you must be a drug addict, but that’s not necessarily true,” Shewan said.

Shewan has had his own checkered past. As a kid, he was sent to live at the Weredale House Boy’s Home, a group home for troubled young men that was located in a few discrete brick buildings off of Dorchester St. and Atwater Ave., across from Cabot Square. Now that space holds the Batshaw Youth and Family Centres, a non-profit organization that facilitates youth protection and intervention.

“I bet no one’s ever asked you […] what happened? How come you’re here?” Shewan asked Gaitan and his friend Shane, another Cabot Square local, on a cold November day in the square.

“No,” Shane said.

“Well, why are you here?”

“Because I had a rough childhood. And my childhood continued to go down the wrong path. On the streets. In and out of jail. Lost my apartment,” Shane replied. “So I kind of got fed up with it, because in my head I’m not going to change. I didn’t want to sit there and lose a house every time I got in trouble. So I said enough is enough, I might as well stay on the streets. Because I don’t know when the next time I’m going to get in trouble is.”

Shane paused for a second and then continued, “This is what people don’t understand. This is what the government doesn’t understand. This is what the law doesn’t understand. We’re at the bottom.”

In the last 10 years Shaughnessy Village, the neighbourhood that surrounds Cabot Square, has become almost completely gentrified, with a significant amount of expensive condo buildings now looming over the square.

In 2008, the city of Montreal commissioned a report on Shaughnessy Village and Cabot Square, examining why it had been a historic gathering place for homeless populations. The report pushed to rename Shaughnessy Village to Quartier des Grands Jardins, and encouraged plans to clean up the area by renovating Cabot Square and building condos.

In 2015, the city shut down Cabot Square for a year and completely reconstructed it—for $6.3 million. The park’s reconstruction has been widely criticised by those who say the redesign has made it inhospitable for Montreal’s homeless. The reconstruction included making the majority of the park cement, with large walkways taking over what used to be grassy areas. The new benches include armrests in awkward places, making it impossible for people to lie down to sleep.

The lack of grass made the park feel bleak and industrial, not a welcoming space. But if the city redesigned the square to get rid of the homeless, where did they expect them to go?

When the Montreal Children’s Hospital relocated to the Glen site in 2015, there was an air of hope in the area that the buildings would be used for affordable housing projects, Gaitan said. Now the historic hospital is in the process of being demolished to make way for a massive $400 million condo project by Devimco Immobilier. The project is said to include 140 units of affordable housing for families and seniors—around 15 per cent of the total units—but nothing specific has been planned for First Nations or populations who are in dire straits.

Most homeless in Cabot Square end up at either the Open Door, a daytime homeless shelter on Rene-Levesque Blvd. West and Atwater Ave., or Chez Doris, a day time women’s shelter on Lambert-Closse St.

The Open Door works out of an old Anglican church, which has been inactive for about a year now. It began as a place where the less fortunate could get out of the cold during the day. In 1988 they started their first official program, which included referrals to professional mental health and drug addiction counsellors, literacy training, showers, and employment assistance.

“People come in and they can eat, they can sleep, they can seek counseling, they can use computers, have their laundry done and get extra clothing,” said Zechariah Ingles, the operations manager of the Open Door. “The idea is that when we close at 3:30 p.m. every day we can send them away with food in their belly, clothes on their back, and be ready to go back out on the streets till the next day.”

The Open Door is the only “wet shelter” in Montreal, which means it is the only shelter that allows people who are intoxicated to enter, no questions asked.

“Most other shelters require some level of sobriety in order to enter. And so when it’s -40 C outside that can be a problem,” Ingles said.

The Open Door recently created the Open Door Housing Program, one of the only social housing programs in Montreal that is specifically for Inuit and First Nations populations.

They also work closely with the Makivik Corporation, “the caretakers of the Inuit in Montreal,” Ingles explained. “They help us out quite a lot in helping get Inuit folks who have been stranded in Montreal back to their home communities, because this is not a place where you want to be stranded for any period of time, especially without support. So we have a crew of volunteers helping get a couple Inuit folks back. They’re taking a convoy of cars, just a bunch of volunteers who drive eight or more hours round trip to get them back to their home communities.”

Unfortunately, the church was sold over six months ago by the Anglican Diocese to a developer, and the Open Door hasn’t been able to lock down a new space. Ingles said that when potential new building owners find out that the Open Door is a homeless shelter, they become less enthused about them taking over.

Chez Doris, diagonally across the square from the Open Door, is a daytime women’s shelter that also supplies two hot meals a day, seven days a week. They provide clothing and hygiene services, financial services, and psychosocial support. Like the Open Door, Chez Doris has partnered up with the Makivik Corporation, where they provide Indigenous women who are currently without a fixed address with an Indigenous caseworker to help them find stable housing in Montreal.

“You could end up dead somewhere,” Shane said earlier in November. “And when it’s too late everyone says, ‘We’re sorry, we’re sorry.’ That’s all they can say. Sometimes the mayor says they’re going to do something, but then when they get in power, they just say,‘Up yours.’”

Later that month, the body of Marc Crainchuk, a well known homeless man in the Cabot Square area, was found under Highway 720. He had been sleeping there that night and was found by his friends the next morning.

Shelters like the Open Door and Chez Doris provide a warm place to stay during the day, but at night the homeless of Cabot Square are left without refuge.

During Mayor Valérie Plante’s campaign, Project Montreal promised they would create 12,000 new social and affordable housing units downtown. Project Montreal also promised to force developers to dedicate 40 per cent of new projects to social and affordable housing.

We’ll wait and see if they follow through.

_600_375_s_c1.png)

ED1(WEB)_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)