Is Quebec’s Language Divide Played Up By the Media?

Linguistic Rights and the Angryphone Movement

Quebecers agree on a lot of things—language isn’t one of them.

In the past year alone, Quebec has made headlines not only across the nation but also internationally with such controversial affairs as Pastagate and Bill 60.

But for Beryl Wajsman, these are more than just headlines in the newspaper. He says anglophones and allophones in Quebec are being discriminated against based on language.

“If you’re a small business employing 15 people, and you put your money to work, many, many small businesses are owned by immigrants and if they can’t be communicated with in [English], based on their needs, they’re just going to close the door,” said Wajsman, editor at The Suburban and publisher of The Métropolitain, in reference to the government’s recent decision to go ahead with a policy introduced in 2011 to only interact with businesses in French.

Wajsman is not alone. He’s part of what Richard Yufe, spokesperson for a group dubbed Canadian Rights in Quebec, called “a movement for language equality in Quebec” on Daybreak Montreal in May 2012.

The movement Yufe referred to is the resurgence of interest groups defending the place of the English language in the province.

Along with the election of the Parti Québécois in September 2012, newsmakers like the Pastagate affair, Bill 60 and, more recently, Creolegate, have caused much ink to be spilled on the hot topic that is Quebec’s language dynamics.

Think pieces of all sorts brought up the idea of the proverbial space taken up by the two languages spoken in the province.

Though officially francophone, Quebec’s—and in particular Montreal’s—bilingualism is often seen as one of its strongest assets. Over 42 per cent of the province’s population speaks both English and French, according to the 2011 Canadian census.

The idea of a language divide in Quebec is nothing new, but it doesn’t have the same momentum as in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s, when approximately 130,000 of the province’s English-speakers left for fear of not being served in their language after Bill 101 passed in 1977.

According to a recently released report from the Canadian Institute for Identities and Migration, 28,439 Quebecers moved away between January and September of 2013—the highest number for that time period in 13 years.

According to Jack Jedwab, the institute’s vice-president, that number is still smaller than that of 40 years ago and may be more for economic reasons than language or politics as it was in the past.

However, many in the media speculated that language tensions might have been, once again, one of the main reasons for the departure of so many Quebecers.

An article titled “More Quebecers are leaving the province” and published on CJAD’s website Jan. 9—the day of the report’s release—linked the statistic to PQ’s rise to power as a minority government.

The same day, The Gazette published an editorial in which it said it’s very likely the province’s “degraded political climate” is “accelerating the outflow” of Anglophones.

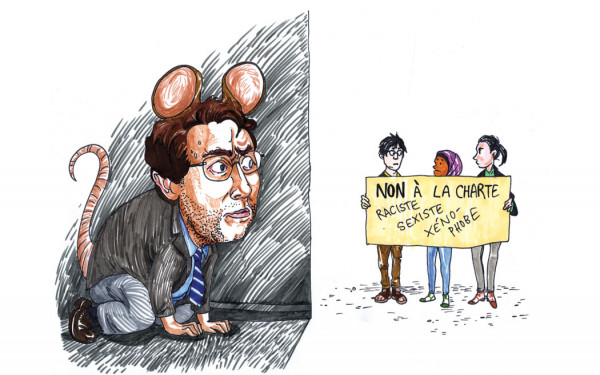

Last May, Montreal journalist and pundit Dan Delmar penned an opinion piece for the National Post entitled “PQ power gives rise to ‘Angryphone’ lunacy.”

“Angryphones” are “the most vigorous defenders of linguistic rights,” as Delmar defined the term in the article. And they’re back.

But they aren’t the only ones outspoken on language rights. In December, the Société Saint-Jean-Baptiste, along with over 100 Quebec figures, including former premier Bernard Landry, launched a campaign termed “Uni-e-s contre la francophobie.” The campaign aims at denouncing the alleged unfavourable portrayal of francophones and the province of Quebec in English media, dubbed “Quebec-bashing.”

As a French-speaking territory located in a country that is predominantly English speaking, and neighbour to one of the most powerful English-speaking countries in the world, Quebec has fought hard to ensure the survival of its official language. The province fights even harder as globalization makes the use of the world’s strongest languages widespread, as French is not included in this category.

Despite polarizing voices, others have tried to soothe. PQ Minister of International Relations, La Francophonie and External Trade Jean-François Lisée is known for reaching out to the Anglo community numerous times, and spoke out against the Office Québécois de la langue française’s initial decision to slap a fine on the St. Laurent Blvd. restaurant Buonanotte for not translating words like “pasta” into French on its menu.

Delmar says such controversies being blown out of proportion is mainly to blame for the province’s ongoing language issue.

“If I write about Angryphones every day, if I write about Societe Saint-Jean-Baptiste every day, you get the impression that these two forces are a lot more influential than they really are. A lot of this crisis has been manufactured by the media,” said Delmar.

“But day-to-day, I think we get along just fine.”

As for Steve Faguy, copy editor at The Gazette, he says neither the media nor the government is to blame.

“Ignorance is the real problem,” he wrote in his blog in December. “Ignorance about Quebec, about the French language, about English Canada, about history, about basic human decency and about the facts.”

_900_597_90.jpg)