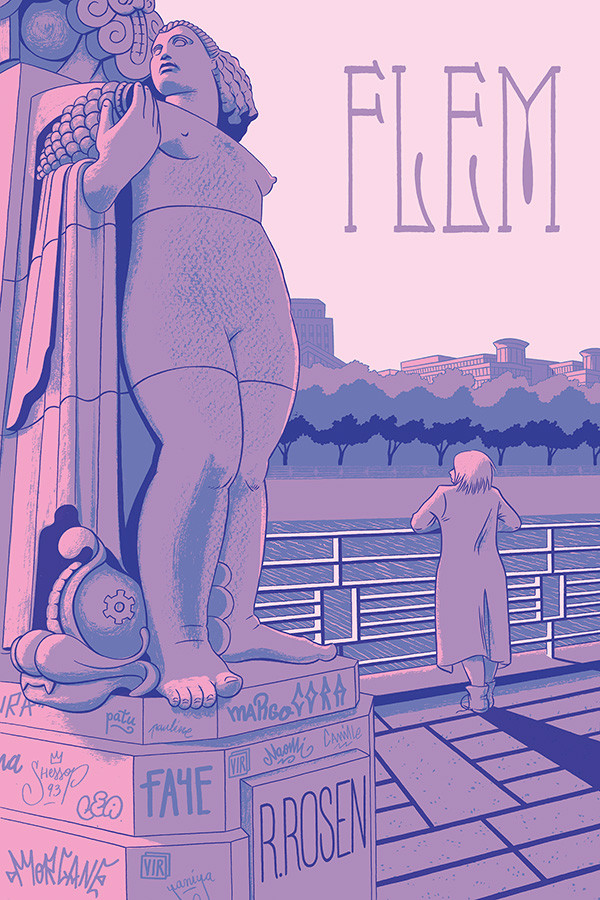

“FLEM” Is About a Girl Who Picks Her Nose⎼But You Will Want a Tissue for Your Tears

Book Review of “FLEM” by Rebecca Rosen

FLEM is about a young woman named Julia who compulsively picks her nose. The graphic novel by Brussels-based, Montreal artist Rebecca Rosen is a short, yet intense read with a climax that feels like a punch in the face.

The book is set in a period sometime around, or slightly before 2002, when assisted suicide was legalized in Belgium. FLEM is a book about mental health, mothers and daughters; but is also about what you owe to a social movement and what it owes to you, when you become unable to help yourself. The bright colours used to illustrate the novel serve to highlight its jarring emotional intensity.

The start of FLEM finds Julia in an unfortunate situation, a spiraling theme throughout the novel, which begins with her flunking out of art school, and running out of the inheritance her mother left her in her passing.

Julia is wracked with guilt because of how she treated her (now dead) mother, and fails out of art school, because her work was considered too repetitive by her instructors. Black and white depictions of woodcuts feature scenes of a mother and daughter throughout the book, though their tone is sinister as creepy things start to take place, like Julia’s mother forgetting her at a store for example.

The book is split into two visual formats that alternate throughout the book. The main story is told in a paneled comic format, bursting with bright jewel tones that usually fit into 4-6 panels per page. The lines are vaguely reminiscent of traditional comics but with a gentler, more illustrative feel to them. The softer lines work well with the bright orange, pinks, blues, purples, yellows, reds, and greens used for the panels that tell the narrative story.

The other format of the book is full page panels, composed of intense graphic black and white lines. These are meant to represent the woodcuts that Julia was kicked out of art school for making too many of. A professor gives her one final chance to show that she could expand her range and progress as an artist. Yet, she is stuck in her trauma, continuing to produce the same work.The fact that these illustrations are in full-page format could symbolize the fact that Julia was stuck in an obsessive loop in her artistic practice.

The black and white images represent memories or reimagined version of memory that Julia has of her mother. The lines are thicker and more graphic than the ones used in the coloured panels, which help to illustrate the intense emotions the depictions of the mother and child are intended to portray.

Julia’s mother suffered from what was implied as depression throughout her childhood, and Julia left home as soon as she could. After leaving for art school she begins to abuse substances, a problem that gets progressively worse throughout the novel. Her relationship with her mother becomes even more strained after moving out.

Both Julia’s and her mother’s mental health issues are a common theme in the story. Julia picks her nose compulsively, making it scab over and bleed again and again. This was likely a nervous tick developed because she was a child forced to grow up too fast. An example of this is having to count out her depressed mother’s medication so she wouldn’t have another “accident.”

FLEM touches on the idea of nature vs nurture when delving into the characters’ mental health. The reader hears Julia’s inner dialogue, and understands that she felt unable to escape from receiving her mother’s depression, genetically.

Julia meets a group of radical feminist activists and ends up moving into their squat. She thinks she has found the perfect, most accepting community and a lover to boot. However, her worsening substance abuse has a negative impact on her relationships.

FLEM addresses the boundaries between activism and activist as her relationship with the feminist collective grows. Julia participates in direct action with the other members of the collective she joins, but her worsening mental health leads to further substance abuse issues. Her spiraling mental health in turn impacts her ability to effectively complete the direct actions she promises the collective she would.

Through Julia’s substance abuse, the author raises the question of how far someone should, or is able to go for a movement. How can you help advance a cause and fight for others when your mental health is in the toilet, and you can’t fight for yourself? How far should the movement or the others involved in it go for you? What do people owe each other, if anything at all?

Rosen raises difficult questions in a short and elegantly depicted format. For those qualities alone it is worth picking up and savouring for an afternoon.