Noam Chomsky urges Canada to sign nuclear ban

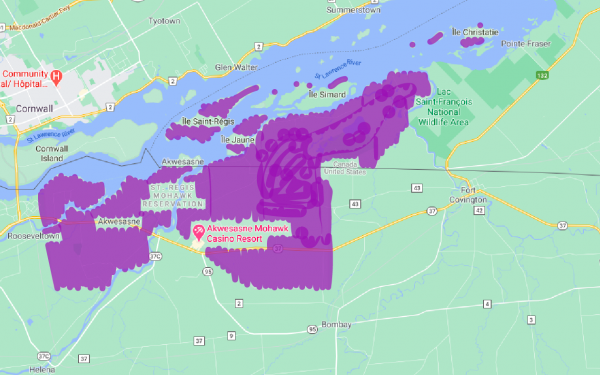

With the Doomsday Clock ticking forward, Prof. Noam Chomsky is urging Canada to sign a new UN treaty calling for nuclear disarmament. Graphic Joey Bruce

Trudeau government uncooperative as new UN treaty calls for nuclear disarmament

Professor Noam Chomsky was 16 years old, working as a camp counsellor, when US nuclear strikes obliterated Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

“[August] 6, 1945, is a day that is indelibly etched into my memory,” said Chomsky.

“In the morning, a speaker at the camp announced that Hiroshima had been attacked by an atomic bomb. Everyone heard the announcement. The next minute, they went back to their normal activities. I was so appalled, I took off and went into the woods to think. I’ve never gotten over that feeling. We are in the exact same situation now.”

In the years since that day, Chomsky, 92, has built a reputation as a historian, political activist, and scholar, who has written more than 150 books on politics and mass media.

Recently, Chomsky held a Zoom conference with the Canadian Foreign Policy Institute to discuss Canada’s refusal to sign the United Nations Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, or TPNW.

The treaty, which was approved by 122 countries in 2017, prohibits affiliated nations from participating in any nuclear weapons activities, including testing, manufacturing, transferring, possessing, stockpiling, using, or threatening to use nuclear weapons.

However, none of the nine nuclear-armed countries—US, UK, Russia, France, China, India, Pakistan, Israel, and North Korea—have signed or ratified the agreement.

Although Canada does not officially own nuclear weapons, the Liberal government did not support the treaty, boycotting negotiations which two-thirds of all countries attended. Canada also voted against a UN resolution in support of the treaty, which was backed by 130 members.

In the years following the Hiroshima attack, the escalating nuclear conflict between the US and the USSR caused the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists to move the minute hand of their Doomsday Clock forward. The new reading, two minutes to midnight, was the closest that humanity had ever come to armageddon, until recently.

On Jan. 23 2020, the Bulletin abandoned minutes in favor of counting seconds, as the minute hand crept forward. That day, the clock indicated 100 seconds to midnight, citing “two simultaneous existential dangers”—climate change and nuclear war.

“A speaker at the camp announced that Hiroshima had been attacked by an atomic bomb. Everyone heard the announcement. The next minute, they went back to their normal activities. I was so appalled, I took off and went into the woods to think. I’ve never gotten over that feeling. We are in the exact same situation now.” — Noam Chomsky

This was, in part, due to the actions of the Trump administration. Under his presidency, the US formally withdrew from a major nuclear treaty with Russia, the INF Agreement, breaking an almost 30 year old pact with the Cold-War superpower. Trump also withdrew from the Treaty on Open Skies, which allowed participating countries to conduct unarmed reconnaissance flights over other countries.

Another arms treaty, New START, almost expired during Trump’s time in office. The treaty limits the number of nuclear warheads that can be deployed at any given time, something that Trump called “one of several bad deals negotiated by the Obama administration.” However, President Joe Biden has said that his administration will seek a five-year extension of the treaty.

Even among countries that have not signed the TPNW, few see nuclear armament in a positive light. A joint statement issued by several former officials of UN member states urged their governments to “show courage and boldness” by joining the treaty. Among them were former Canadian prime ministers Jean Chrétien and John N. Turner, and former defence minister Lloyd Axworthy.

The Liberal government has gone on record saying that its decision to opt-out of the agreement was partly due to its allegiance to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. NATO is a military alliance between 30 countries, including Canada, the US, the UK, and France, which endorses the possession of nuclear weapons as a form of deterrence against nuclear warfare. It is unclear whether Canada’s participation in NATO would stop it from taking steps to ban nuclear weapons at home.

“Should Canada be part of an international military organization that is dedicated to the use of nuclear weapons, meaning terminal destruction? That’s a question for Canadians to answer.” Chomsky said. “My own feeling is that, if membership is continued, it should be contingent on the commitment to joining the treaty and to act in that direction.”

Chomsky was also critical of several NATO countries, including Canada, continuing to support the US in military endeavours. “To me, it seems criminal for anyone to contribute to the development of weapons systems that are capable of destroying life on earth.”

“To me, it seems criminal for anyone to contribute to the development of weapons systems that are capable of destroying life on earth.” — Noam Chomsky

Chomsky cited the 1995 document “Essentials of Post-Cold War Deterrence” as an example of the problems with America’s attitude toward nuclear warfare. The document, drafted under president Bill Clinton, is still used as the basis for US military strategy.

The document is known for encouraging American military officials to act “irrational and vindictive,” escalating conflicts to scare their political enemies: “It hurts to portray ourselves as too fully rational and cold-headed…This essential sense of fear is the working force of deterrence. That the US may become irrational and vindictive if its vital interests are attacked should be a part of the national persona we project to all adversaries.”

The document also advocates a nuclear first-strike policy—launching nuclear weapons as a preemptive, surprise attack.

While NATO adheres to a doctrine of armed nuclear deterrence, Chomsky is unconvinced that intimidation is the best way forward. “You can argue that the threat of species suicide has deterred powers from waging war,” he said, “but we have to balance that against something else: the possibility that nuclear weapons will be used.”

Chomsky recalled one moment during the Cuban Missile Crisis when, cut off from their superiors, the commanders of a fleet of Russian submarines had to decide whether to launch their arsenal of nuclear-tipped torpedoes. “There were three commanders in each vessel, and all three had to agree to launch them. In one submarine, two commanders agreed, and one, Vasily Arkhipov, didn’t. We’re alive.”

America’s threatening reputation as a nuclear power, Chomsky argued, stops Canada and other countries from supporting anti-nuclear efforts. “We should remember that the world is run kind of like the Mafia. Canada is not in a position to confront the Godfather, the US, and neither are much more powerful states.”

Chomsky mentioned that the European Union, though strongly opposed to US trade sanctions on Iran, conforms to American interests, “because if they don’t conform, the Godfather throws them out of the international financial system. So they complain, but they conform.”

“The world doesn’t have to be like that,” said Chomsky. “Alternative financial systems can be constructed. Pressures can be applied to the US. Canada can do things by itself.”

“We should remember that the world is run kind of like the Mafia. Canada is not in a position to confront the Godfather, the US, and neither are much more powerful states.” — Noam Chomsky

To some extent, Canadians have done their best to limit the spread of nuclear weapons on national soil. Vancouver is a designated “Nuclear Weapons Free Zone,” as is Regina, Saskatchewan, and other cities in British Columbia. But without support from the federal government, these localities make up a small percentage of a country fully geared to help its nuclear allies.

Nonetheless, grassroots efforts to curb the harm done by nuclear warfare have helped in the past. “The huge uprisings in the early ‘80s had an effect,” said Chomsky. “Not much, but some. They chipped away at the danger, and they’re part of the background for the INF Agreement of 1987.”

Today, groups like the Canadian Foreign Policy Institute continue advocating for nuclear disarmament, working to spread awareness of the issue online. Their website hosts articles about Canadian foreign affairs, including nuclear arms, and their page dedicated to Chomsky’s conference has a directory of resources designed to help readers learn more about the topic.

In recent years, officials have warned about the threat of non-state actors supplied with nuclear arsenals. Graham Allison, Professor of government at Harvard University, says the threat of nuclear terrorism is more real than ever. In unregulated hands, nuclear warheads could become potential “dirty bombs,” weapons that contaminate the surrounding area with lethal radioactive particles.

“A dirty bomb in New York,” said Chomsky, “would make 9/11 look like a minor accident.”

It would also mark the second time a radiological weapon was deliberately used. The first was detonated by the US military on 16 July 1945 during the infamous “Trinity Test,” a part of the Manhattan Project.

“During the Trinity Test,” said Chomsky, “Hans Bethe and Enrico Fermi placed bets on whether Earth's atmosphere would be ignited by the blast, destroying all life.”

“It was considered a remote possibility—but not impossible.”