Inside Montreal’s activist postering subculture

Photo Esteban Cuevas

How local artists are taking community activism to the streets

Whether Stefan Christoff is setting out to “make racists afraid again,” advocate for exploited workers, or defund the police, he begins in his kitchen, whisk in hand, a smell faintly like bread rising to his nose. The concoction is one part flour, six parts water, and in about 20 minutes, it will be a smooth, sticky paste.

In the winter, he must work swiftly, his adhesive still scalding. The wheat paste will freeze quickly on a metal pole, but if he’s fast and the mixture is hot enough when he dips the brush, it will work.

Christoff, a Montreal activist and community organizer for nearly 20 years, is a devotee of street postering, a politicized style of street art that still thrives in the city, even in the age of social media. “I think any sort of real democratic discussion takes action,” he said.

In a city renowned both for its dynamic arts scene and its political tensions, the street itself is a battleground of ideas, even as it teeters on the edge of commercialization. The world feels rapidly more virtual, but a cacophony of posters—many defaced or covered—cram street lamps, walls, mailboxes, and construction sites, fighting to be heard.

“You can’t just put your work on the wall and be like, ‘That’s the work that I did and if someone goes over it then it’s gone forever,’” said Chris Robertson, owner of screen-printing shop La Presse du Chat Perdu and a collaborator of Christoff’s. “You’ve got to keep pushing, you’ve got to keep doing work and putting it out there.”

“I like the idea that it stays up for a while, but it’s not totally permanent and it’s not impossible to get off,” said Christoff. “[...] [Y]ou just need hot water and a scraper, that’s it, and it takes like 10 minutes.”

The ephemeral nature of the art form reflects an ever-changing zeitgeist. “A lot of what I put up is not that super artistic but it is creative in a sense, and I think it’s an evolving space depending where we’re at politically in the moment,” said Christoff.

Taking the streets

Many prefer the cloak of darkness, but Christoff often goes out in the light of day, keeping his tub of wheat paste hidden in a reusable shopping bag to avoid being hassled by the police.

His openness about what he does is a political decision—an embodiment of his belief that street art is not something that should be hidden. “I do those things for a reason and I don’t want to be doing that in the dark. I do that intentionally in a public way,” he said.

Those who plaster our public spaces with messages of action or solidarity see the medium as a mode of intervention.

“What’s good about street art is it takes it back to messaging on the street being a space for public democratic debate as opposed to being mediated by who’s going to pay the most to get a message out there,” said Christoff.

Claiming space for community activism is an essential component of street art, said Kevin Lo, a part-time faculty member in the design and computation arts department at Concordia University and the owner of LOKI, a design and communications studio. “It’s hard to measure any sort of practical effect, but I’d like to think that it shows a certain form of contestation,” he said.

Lo often designs posters and has at times put them up himself. “As a designer, I feel it’s really important to do this kind of work and get it within what I would call a public sphere,” he said. Some post on platforms such as Instagram to strive for the same effect, but for Lo, reaching the public sphere primarily means getting into the street.

“The way social media tends to work and the way the internet tends to work these days, it’s not so much a public sphere anymore,” he said. “Everyone has opinion bubbles.” He noted the way algorithms dictate the messaging each person sees, a corporate filter that doesn’t apply to the street.

“I have really mixed feelings about social media,” said Lo, who spent years as an interactive designer working in advertising. There’s amazing activism being done on social media, he said, yet the platforms themselves are addictive, meant to be commercialized. Success is quantitative, and engagement itself is commodified. A poster on the street, in comparison, may not grab a person’s attention as well, but it’s disruptive. “I think that’s what makes it powerful,” he said.

“I think our city streets are more vibrant and more meaningful when the debates of our time are expressed on them,” said Christoff.

While Christoff often goes out in the daytime as an expression of his philosophy, there is ample reason to avoid it.

“Stefan goes out during the day, which is not my style,” said Robertson. “I’m more of a go-out-at-midnight kind of person.”

He likes that people will leave him alone at night, though he recognizes this is a privilege he has over street artists who present as women.

The other issue, aside from unwanted attention from passersby, is police harassment.

If someone is putting up commercial posters, such as for a concert venue, they aren’t likely to get a hard time, Robertson said, but this can change depending on the content. “If you’re putting up work that’s about defunding the police, things like that, then they’re really going to have a problem with you and they’re going to start trouble with you,” he said.

Yet, postering is not illegal, at least when it comes to public property in Montreal. A bylaw prohibiting the practice was struck down in 2010 by the Quebec Court of Appeal in a case involving Jaggi Singh, a well-known activist in Quebec.

Singh was fined under the bylaw in 2000—not the first time he had been charged—when he was out postering near Ste-Catherine St. E. and Berri St. for the Montreal Anarchist Bookfair. He was found guilty in 2003 but was acquitted on appeal in 2010.

The Quebec Court of Appeal found the bylaw infringed on the freedom of expression of Montrealers because there were not many spaces designated for the activity. Postering had been allowed on boards known as babillards, but these were few and far between.

Singh told the court that in years of postering, he had only noticed two babillards, both near McGill University, and that because they are so small, using them would require covering up posters for events that had not yet happened.

Posters at the time were also permitted on construction hoarding—the fences surrounding construction sites—but these were often plastered with commercial advertising.

“Most people think it’s illegal, but it’s actually not illegal,” said Lo. “Cops will still harass you for it because cops still think it’s illegal too.”

Public reception can range from love to hate.

Lo recalls his first experiences with postering when he was still taking classes at Concordia. He had designed a series of anti-consumerist posters as part of a project that related to intervening in the public sphere. He pasted them on glowing, tubular advertising columns so that they covered up commercial messages.

Most of his pieces were torn down quickly, but he recalls finding a message on one still left intact, written in the corner in ballpoint pen.

“Merci beaucoup,” the stranger wrote. “Je t’aime.”

“It sparked in me this idea of how powerful design can be to actually communicate with people and to create a dialogue and create an interaction,” said Lo.

However, the messages can also attract venom.

Lo notes the resurgence of far-right groups in Quebec. “I think we’re seeing with some of these more extreme groups, extreme-right groups, they also like to take public space in these ways as well,” he said.

Christoff, for his part, recently received hateful calls to a phone number he included on posters advertising an event to benefit Beirut following the devastating explosion at its port in August.

The man who called was incensed by the fact the posters, now defaced in black marker with the word “français,” were in English. He complained the posters had no place in Quebec because they were not in French and because they supported the rights of immigrants. He swore and said he hoped Israel would invade Lebanon again.

French versions had been posted nearby, Christoff said.

The impact of street art

“You usually never know if you got through to people,” said Robertson. The real change is effected by community organizers, he said, but the role of postering is to bring awareness, to motivate people, and to bring ideas into people’s consciousness.

“A lot of people are getting involved in these campaigns because of those posters,” said Muhamed Barry, a member of Solidarity Across Borders and the Immigrant Workers Centre. He isn’t involved in posters, but he believes they help local causes and the people they seek to support, such as new immigrants.

“I think our city streets are more vibrant and more meaningful when the debates of our time are expressed on them.” — Stefan Christoff

“They see the posters somewhere in the city, they read, they go online and call us,” he said. Often these people are victims of exploitation.

Christoff sees postering as one mode of action, and his activities often collide. Like Barry, he is a member of the IWC. Among other things, the organization advocates for Dollarama warehouse workers it says are underpaid and labouring in unsafe conditions.

Christoff takes pleasure in taking this message to the doorstep of the dollar store’s outlets.

“It’s very important to speak out because a lot of people are exploited by employers in Canada,” said Barry.

The poster, designed by Robertson, reads, “Justice for Dollarama Warehouse Workers, Status for All,” a reference to calls for regularization to be granted to all undocumented migrants and temporary workers in Canada. The poster’s thick blankets of black ink convey gravity and draw the viewer’s eye to the workers gathering in the centre of a warehouse floor.

“The worst thing would be for people to walk by and just not even care, not even think about it,” said Robertson, but the goal is not necessarily to change minds. “Street art is supposed to be confrontational, but the other side of it is the sharing of love as well, to the people the work is talking to.”

_1200_900_90.jpg)

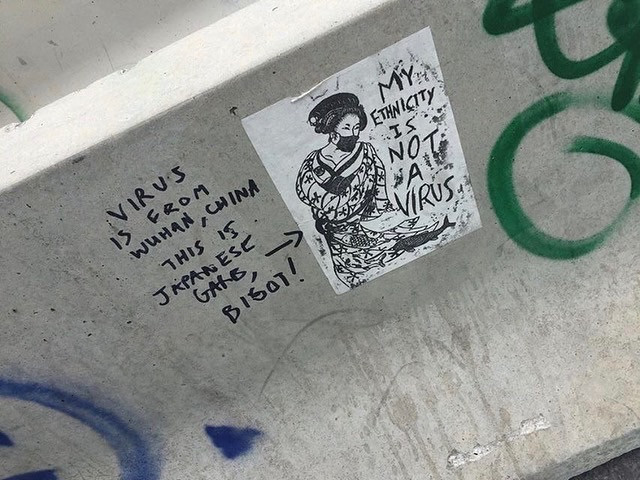

This year, drawing on his identity as a Japanese-Canadian of mixed heritage, Robertson’s work has focused largely on anti-racism in the wake of COVID-19. One of his pieces is a black-and-white depiction of a woman dressed in traditional Japanese attire, a mask covering her mouth. It reads, “My ethnicity is not a virus.”

In one instance, somebody wrote in marker on the concrete next to the poster: “Virus is from Wuhan, China. This is Japanese garb, bigot!”

“I was talking about evoking a strong emotion, positive or negative, and that is the goal, and it is,” said Robertson. “But especially with this work, which is so personal to me and my experience, when people deface this and write racist things on this, that hurts.”

Another poster, designed by Jessica Sabogal, an Oakland-based muralist who is a friend and collaborator of Robertson's, reads “Whiteness lacks awareness but always has an opinion." It has been defaced in multiple locations.

Still, the value of such artwork can go beyond simply making people question their views.

“People can feel like other people are sticking up for them,” Robertson said. “As much as I’m trying to talk to the people that are perpetrating the racism and stereotypes and stuff, it’s also for the people in my community to feel like their voice is being heard.”

“I think for people who feel alienated, I’d like to hope that these sorts of interventions help,” said Lo, who believes creating visibility and taking space can be inherently empowering.

“I think in some ways what’s important is for someone, even someone like me, if I can see a poster that is aligned to my values and that is beautiful and is energetic and has a strong message, it reinforces that for me and makes me feel less alone in the world and in the city,” he said.

Besides this, a poster can have a practical value: it can invite residents to attend something. It can give the date, time, and place.

It’s also something people do because it’s what they feel they have to offer. “I’m not an essayist, I’m not a musician, so those aren’t my forms of communication,” said Robertson. “This is. Whether it’s the most powerful one, I don’t know.”

The convergence of artist and activist

“I think it’s still quite a challenge to mobilize artists, and it’s still quite a challenge to get activists to appreciate the role that art has, so there’s definitely still a challenge, but I think slightly less of a challenge in a city like Montreal than elsewhere,” said Lo.

“If you can’t sell Fido phones, then it doesn’t get the same notoriety or recognition as these other things.” — Chris Robertson

Lo identifies with social anarchism, a philosophy that links individual autonomy and community solidarity. He describes a political awakening in the late 90s and early 2000s around the fight against corporate globalization, influenced in part by writings from Mexico’s far-left Zapatista movement. Lately, he recognizes psychological motives in the way he channels his creative energy, finding that Montreal has a special way of bringing out this convergence.

Even in Montreal, however, commercial influences are everywhere. Robertson resents that the international MURAL Festival in Plateau-Mont-Royal has no issues securing funding each year, yet something like Unceded Voices, a mural festival celebrating female Indigenous artists, struggled to stay afloat and is now defunct.

“If you can’t sell Fido phones, then it doesn’t get the same notoriety or recognition as these other things,” he said.

Street postering nevertheless has a way of resisting commercialization. Some posters are photocopied, but for reasons such as authenticity and cost, many are produced by other means, such as screen printing.

This process involves burning stencils into mesh screens that then have ink pushed through them. It’s the way a lot of these posters traditionally get produced, according to Lo.

“I think in some ways the actual handmade quality that comes out of a screen print, there’s something there that is special, there’s something that has a certain aura that I don’t think you can get with digital reproduction,” he said.

It’s tactile and smells of ink. “Each print is actually a unique object where if you push a little bit harder, it’s going to be darker. If you let up in a certain area, it’s going to be a little bit lighter. If the screen gets a little bit worn out, there’s going to be a little bit of leakage,” he said. “I think there’s also that aspect of the kind of humanness of that printing. It has a little bit of that imperfection that I think is really important to give it that sense of aura and that sense of materiality.”

Christoff has a stack of posters at home that were designed by Lo and came off Robertson’s screen printing machine.

This is the pile Christoff reaches for one recent afternoon, the wintery air hovering around -4 C. Steam pours from his glue, hot off the stove, as he rushes to Plaza St-Hubert in La Petite-Patrie with a friend from New York.

They find a lamppost across from Sabor Latino at Bélanger St. Christoff dips his wallpaper brush in wheat paste and paints the metal pole. His friend, who has come along to look out for patrol cars, flattens a sheet against it. Christoff brushes the poster with a coat of glue.

It’s a simple piece, nothing more than bold, black lettering on white paper. No one knows how many will see it before it fades, before it gets scraped off, covered up, or defaced.

No one knows how many will take its message to heart:

A B C D E F U N D T H E P O L I C E.

This article has been updated to clarify the designer behind the poster that reads "Whiteness lacks awareness but always has an opinion." It was designed by Jessica Sabogal.