Canadian Armenians advocate for community overseas

Armenian community in Canada reflects on ethnic cleansing in contested region of Nagorno-Karabakh

The contested region of Nagorno-Karabakh, a majoritarily Armenian inhabited enclave internationally recognized as a semi-autonomous part of Azerbaijan, is seeing most of its Armenian population flee following the Sept. 19 Azerbaijani assault in the area.

Over 100,000 refugees have fled from Artsakh to Armenia, most of which have had to go without essential supplies for days according to the United Nations refugee agency.

The Republic of Nagorno-Karabakh or Artsakh is a separatist ethnic-Armenian enclave within the borders of Azerbaijan. It was occupied by Armenia for decades before Azerbaijan won a fight in 2020 with the aid of the Turkish government and therefore gained the area as territory following the surrender of the Armenian government.

On Sept. 19, Azerbaijan launched a military operation on Nagorno-Karabakh labeled as an “anti-terrorist” campaign by the country’s defense ministry. Following the attack, over 200 people have been killed, leaving Nagorno-Karabakh with no choice but to capitulate due to their being overwhelmed with the Azerbaijan army.

Tensions between the two regions had already been running high due to the nine month blockade that went on beforehand, during which the importation of food was completely prevented.

Armenian National Committee of Canada (ANCC) executive director and Ontarian of Armenian origin Sevag Belian explained that Nagorno-Karabakh was under total blockade before the events of Sept. 19 and that the people barely had any food, medicine, fuel and other basic necessities. “Not only these people were attacked, but ten months prior to that, they were being starved by Azerbaijan, and the media didn’t talk about it until the people were forcibly uprooted and we witnessed one of the worst refugee crises.”

Through the difficulties of her community overseas, Maral, who did not want to disclose her name for safety reasons, a student of Armenian descent at Concordia University expressed her commitment to raising awareness on the issue.”Personally for me, everything I do has to be for this cause right now, I can't look away. I can't distract myself, I can't pretend it's not there. I just can't have normal conversations. I'm not gonna fake anything, I think people should know what's happening.”

Maral shared her pain regarding the bombings from the capital of Azerbaijan, Baku, that killed over 200 people. “When you feel that heart-to-heart connection to a land and then it’s being bombed, you kinda feel like you're losing someone,” she said, “the first emotion I felt was why am I here in Montreal? Why am I not hurting with my people? I felt guilt and resentment and anger.”

Matthew Doramajian, an engineering student at Concordia, was born in Canada but has grandparents immigrated from western Armenia to Egypt and then Canada in the 1960s. He is also feeling deep sadness and hurt. “I feel my nation is my family so even though I'm so far away, it's like my own family being violated.”

Although he feels this way, Doramajian is nonplussed about such events occurring. “It's almost horrible to say, but it doesn’t surprise me. As bad as it is, there's nothing us Armenians haven't seen before,” he said. “Right now, I witness my brothers and sisters being massacred, just how my parents in the 80s and 90s also saw their brothers and sisters being massacred, just how my grandparents witnessed massacre as well. It's continuous, we feel helpless; it's not a comfortable feeling.”

Belian voiced his disappointment on the reactions happening on a global level. “The fact that 100 years later the Armenian people are once again witnessing the same thing brings a lot of frustration and outrage in us because the international community really didn’t take their responsibility to protect vulnerable populations seriously” he said. He continues,“there's a sense of devastation, there's a sense of haunting memories coming back and also a sense of anger and frustration that this all happened in the 21st century, a modern day genocide.”

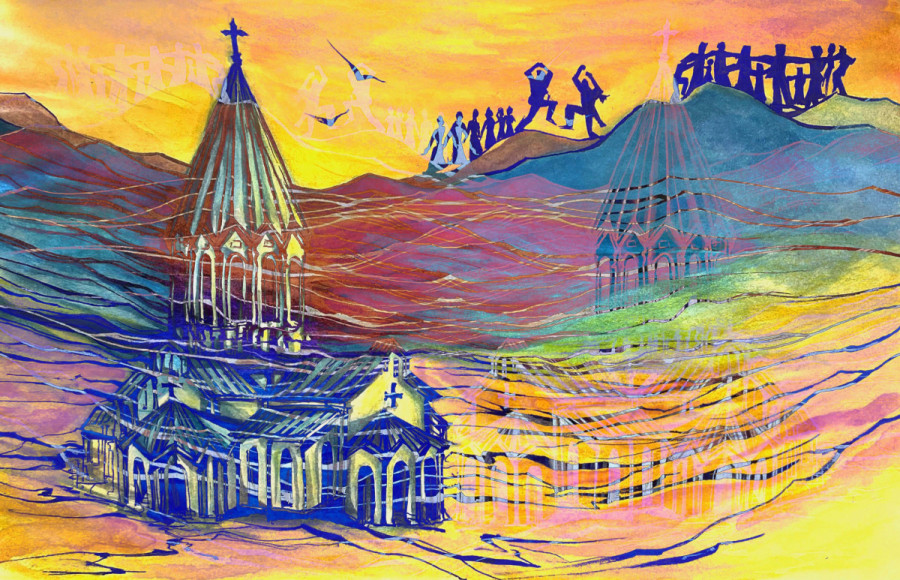

Belian delved deeper into his perspective of the situation: “Forcing people to leave their land under pressure, it’s a form of genocide,” he said. “It deprives them of what they hold most dear to their heart, and that is their belonging, their spatial recognition, and their connection to the land that has been their indigenous land for millennia.”

Maral started a journey in activism, standing in protest in front of McGill University. She wore a traditional Armenian dress, a skirt called a taraz, and played Armenian music to bring awareness to the crisis overseas. “It was just this symbolism for pain and suffering. It was human, not just tied to culture, just like the human pain that comes with terrorism. It’s something else when you stand with your people.”

There are doubts by the Armenian community on whether mainstream media is properly covering the conflict. “We were covered by CBC news and anytime I said the word genocide, [...] the news cut off the word,” Maral said. “I think it's important for people to know who the aggressor is. The world seems to not want to be upfront about it.”

Belian explained that the media comes in only when an issue reaches a very critical point. “This sudden attention that we're getting is like bringing flowers to someone's funeral,” he said. “After everything is done, after all the damage is done, the media takes interest and starts talking about the misery of the population,” Belian said.

Doramajian believes interventions from international governments are essential to ignite change.

“In politics, it is not the crime that is important, it is who is doing it. If they are a threat, then countries will push for their crimes to be punished. If not, they don’t care,” he said.