Canada Chooses Oil Over People (Again)

The Confrontations With the Wet’suwet’en Nation Show the Federal Government Isn’t Interested in Real Reconciliation

The relationship between the Canadian government and Indigenous peoples continues to be one of reconciliation only when it serves federal interests.

In the months leading up to the October 21 federal election, elected officials’ work, as well as the promises they made during their campaign, will increasingly come under scrutiny. Nobody will be pressed more than Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, who recently has come under fire for the treatment of activists and community leaders from the Wet’suwet’en Nation in British Columbia.

On January 8, 14 people were arrested by the RCMP while protesting the Coastal GasLink pipeline that is expected to run 670 kilometers included through a part of Wet’suwet’en which remains unceded land. The protesters had set up a checkpoint to halt the pipeline workers in the Gitdumt’en camp, just south of Houston, B.C. . All five clans that make up the Wet’suwet’en Nation have unanimously opposed the pipeline.

The nearby ecosystem, as well as the 20 First Nations surrounding the pipeline will constantly be at risk of pollution and environmental destruction from normal use and from accidents, but that’s not all. The aggression shown by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police demonstrates just how hypocritical Canadians are when people brag about Canada’s human rights record. While we uplift this idea that we are everyone’s “friendly and progressive neighbors to the north”, it is finally becoming increasingly clear that it is a very selective kind of progressivism. The kind that inexplicably still does not extend to the peoples that have lived on this land for centuries longer than the oldest of colonizers.

While performing the arrests, Wet’suwet’en protestor Liam Moore explained how police arrived in full tactical gear, and may have caused fractures in his hand. The RCMP have installed roadblocks as well, effectively cutting off access to the access to the the Unist’ot’en Camp, halting communications and the transport of food and medical supplies.

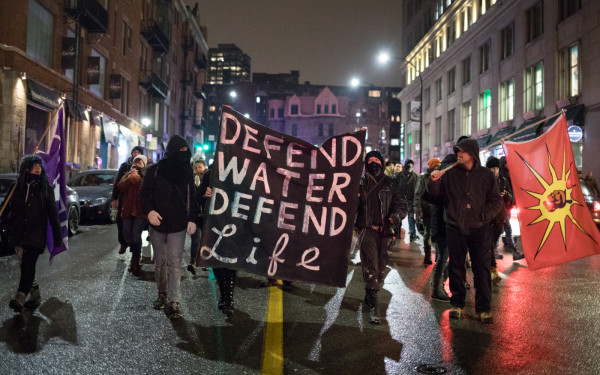

The arrests came after after the B.C. Supreme Court granted the builders of the pipeline an injunction allowing them to use the road to the construction sites unimpeded. An elder, as well as Gidumt’en Clan spokesperson Molly Wickham was among the 14 people arrested. After news of this began to circulate, over 55 cities marched in solidarity with the Wet’suwet’en Nation, including Montreal.

The Supreme Court decision comes off the fact that Coastal GasLink, a subsidiary of TransCanada, reached agreements with the band councils of all 20 First Nations along the path of the pipeline. This is where the difference between band council and hereditary chiefs come into play.

Hereditary Chiefs are the traditional form of governance that most First Nations had before they were colonized. Band councils were only introduced as federal law in 1876, and were designed to act as an elected government body. However, while they are elected, they are held accountable to Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada.

“What you see in the case of what’s happening currently in B.C. is a tension between the interests of a band council and individuals in the community that are recognized within the community — not necessarily outside of the community — as community leaders,” said Jeffrey Ansloos, a member of the Fish River Cree Nation and a professor at the University of Toronto to Global News.

The notion that all of this happened on unceded land should also be the primary focus. The arrests happened in Wet’suwet’en territory against people who were protesting an issue that puts their very way of life in danger. What we are seeing now is the continuation of the systematic destruction of a people whose presence and culture long predate any form of Western influence. Above all that, the action of the RCMP fly directly in contrast with global measures set in place to protect Indigenous land.

In the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, Article 10 outlines that “Indigenous peoples shall not be forcibly removed from their land or territories.” With all this talk of reconciliation coming from Justin Trudeau and the Liberal Party, it is becoming painstakingly obvious that it will remain just that: talk.

Trudeau has made reconciliation a key aspect of his win in 2015 and continued to press the issue as Prime Minister but crises like this are what will permanently stain his legacy. Acting as the young, woke, and hip world leader and having everyone in the global community swoon over you only goes so far when you’re violating the human rights of your people. This, coupled with selling arms to Saudi Arabia, which are actively contributing to the humanitarian crisis in Yemen, go a long way in showing just how bad the Trudeau government’s human rights record is.

With the entire world watching, Canada can no longer hold themselves up as this ultimate utopian purveyor of human rights. Our treatment of Indigenous people, their culture, and their most basic rights even to this day is a national tragedy, and should be addressed as such. What’s happening in B.C. isn’t an anomaly, it’s the Canadian reality.