Asexuality, Explained Through Cake

The Inside Joke I’ll Never Get

Do you like cake? Well, imagine that everyone around you is OBSESSED with cake.

All your friends talk about how much they crave it, how they feel when they have it.

They describe its texture, feeling, fluffiness, and give you detailed accounts of the last time they had cake and who they had it with.

But for you, cake doesn’t ever really cross your mind. Of course cake is great, it definitely tastes nice, but to think about it constantly?

Quite honestly, you didn’t even feel like you were missing out on much before you ever tried it.

Yet, everywhere around you, people have cake all the time.

Maybe you just haven’t had the right type of cake, they’ll tell you.

Maybe you just need to try it again, maybe you don’t want cake because of some sort of cake-related trauma you experienced as a child.

Are you even sure you don’t want cake? No one doesn’t want cake.

You’ve probably guessed by now that cake, here, should be replaced with sex.

The cake analogy is often used by aspec (on the asexual spectrum) people to describe what asexuality feels like.

Asexuality is defined by a lack of sexual attraction to other people.

People who identify as asexual, therefore, don’t feel much of an interest or need for sexual activity.

It’s also referred to as a spectrum because, just like many sexual identities, there are varying degrees of sexual attraction.

People who identify as completely asexual feel no sexual attraction at all, while those who feel they are somewhere between sexuality and asexuality will sometimes identify as “grey-ace” because it’s in the grey area on the spectrum.

Some people also identify as demisexual, which means they need a strong emotional connection with someone else in order to find them sexually attractive at all.

People will also slip in aromanticism next to this spectrum, since the lack of romantic attraction is often linked very closely, though they are still two different components of sexual identity.

Does it mean people who are asexual have no interest in sex? Not necessarily.

Does it mean none of them have sex? Of course not.

Usually, it just takes another element in order for them to get turned on, such as the idea that it’s an intimate moment with their partner, or that it makes their partner happy, for example.

For me, the desire to have sex never came naturally, only as a result of building social pressure.

I’ve had to shrug off a few outraged “What?!” reactions after telling some of my closest friends that, if I had to never have sex ever again, I’d be fine with it.

It never clicked with me that calling someone hot equals wanting to sleep with them, or that when two people leave a party together or hang out late at night, it probably means they’re having sex.

I never understood how two people can “accidentally” have sex.

When my friends have expressed their sexual frustrations to me, I’ve never been able to answer with more than a confused, “Why don’t you just, I dunno, read a book or something?”

As someone who identifies as grey-ace, I’ve never felt particularly out of place in feeling close to no sexual attraction or desire.

Perhaps it’s because I was raised by a strict Taiwanese tiger mom, who forbade me from having sex until I’m in my late 30s (sorry ‘Ma).

I was never aware of just how different my perception of sexuality was until late into my high school years, when my friends started making comments about random guys’ attractiveness, guys whose looks I felt completely indifferent about (sexually).

By that point, I already had a feeling I wasn’t entirely straight, later putting two and two together to discover I was bi (sorry again, ‘Ma).

I didn’t think anything was wrong about my lack of sexual desire, in fact, I didn’t even know there was anything abnormal about it at all.

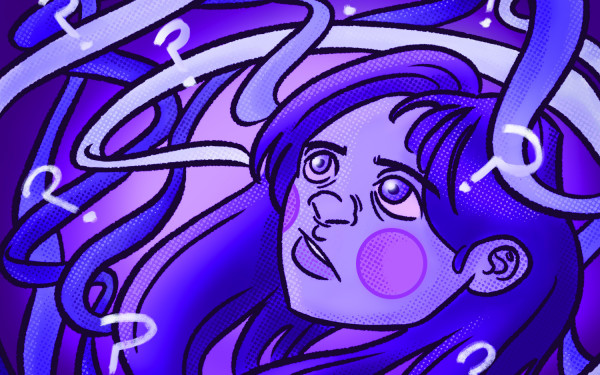

It’s like sexual attraction was the one inside joke everyone had and that I never got.

Once I started college and became close with a friend who also identifies as grey-ace, that’s when I discovered we were the odd ones out.

Once I started having an active sexual life, the overwhelming sensation of indifference towards sex confirmed to me that I was grey-ace.

Don’t get me wrong, sex has been great.

“It’s like sexual attraction was the one inside joke everyone had and that I never got.”

But to me, it’s exactly like having a slice of cake: I enjoy it while I have it, but when I don’t, it’s not on my mind at all, I don’t really crave it, and I don’t seek to have it every day.

What I’ve gathered makes me different from people who aren’t asexual is that my perception of the world puts sexuality very far away.

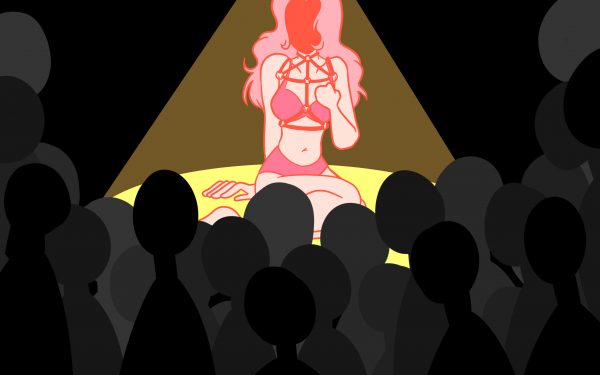

Porn has the same effect on me that any regular movie would.

Content or products related to my sexual fantasies or kinks (asexual people can have kinks too!) will be acknowledged as something I like, but will rarely turn me on.

Instead, these will remain something that I enjoy incorporating in the bedroom.

People I find attractive are just people whom I think have nice features, and I most certainly don’t think about having sex with them, almost ever.

Personally, I’ve never talked about asexuality with anyone who wasn’t open to a discussion about it, and I’m lucky to have such an accepting entourage.

I know some people whose coming-outs have been met with annoying amounts of “Maybe you just haven’t met the right person”; “You’re just not mature enough”; “Like, how come?”; “Did you go through something traumatic when you were a kid?”; “You’re just not ready”; “Really? But you’re so (insert a nice compliment).”

I could go on.

It’s wild how people from older generations are so pro-chastity, until they hear you have no interest in sex, isn’t it?

Sexual liberation movements have taught us to embrace the good, the bad, and the ugly of sex.

They have allowed movies and books to be a lot more descriptive and open about it, to educate people about healthy sexual activity, and to make a lot of us more reassured and confident about our sexualities.

But it’s also made it widely understood that, in Western society, the portrait of a “normal” sexual lifestyle starts being painted in someone’s late teenage years, and typically contains more than a few sexual partners.

For a lot of people who identify as asexual, who haven’t quite figured out their sexuality yet, or who simply aren’t ready for the commitment of losing their virginity, this portrait builds a lot of pressure, especially at an age where comparing ourselves to others still takes up a large part of our identity.

I’ve heard more than one 18 or 19-year-old express fear about not having had sex yet, and even I, at that age, started second-guessing whether it was normal that I had only ever had one sexual partner. Asexual erasure is, I think, an unfortunate by-product of setting sexuality as a standard. I don’t think the sex-positive movement is negative at all, but I do think that if we’ve improved the way we talk about sex, it’s also imperative that we learn to be comfortable with non-sex.

In some ways, the ideas that nudity isn’t sexual and that sex isn’t the ultimate form of intimacy are good ways to start having this discussion.

But in my experience, the expectation of sexuality has only been intimidating and uncomfortable.

In the context of asexuality, it has led to the infantilization of people who are aspec, and in a lot of cases has pressured ace people to have sex, simply because they didn’t think not wanting to have sex was an option.

Some scientists have even questioned whether or not it’s an illness, but this isn’t a widely discussed topic because few people know what asexuality is.

Over the years, I’ve become a lot more comfortable in my asexuality, and though I still struggle with the social pressure of having a more adventurous sexual life, I’ve come a long way from the frightened young ace I was in high school.

It has definitely helped to find other people who shared this identity, so I’d like to invite anyone who recognizes themselves in this piece, or even those who are just curious to learn more about asexuality, to reach out to me.