Improving Montreal for the City’s Youth

CjM publishes Recommendations for Future City Council Ahead of Municipal Election

With the Nov. 3 municipal election fast approaching, the Conseil jeunesse de Montréal, the city’s youth council, has decided to get involved in the debate and bring youth-related issues to the attention of the candidates in the race.

The council, which aims to represent the interests of Montrealers aged 12 to 30, published a document on Sept. 23 outlining the actions it would like to see Montreal’s next municipal administration take in order to make the city a better place for its younger residents.

The document draws upon the council’s previous research, reports and policy papers to make specific recommendations in five policy areas—governance and citizen engagement; communications and information; land use, sustainable development and housing; sports, leisure, culture and heritage; and solidarity and social inclusion.

“I’d say what was most important for us was deciding on recommendations that were as […] concrete and shovel-ready as possible,” CjM President Michael Ryan Wiseman told The Link.

Wiseman, who recently completed a master’s degree in public policy and public administration at Concordia, said the youth council has shifted in recent years toward making more tangible recommendations “that can provide a clear direction to city leadership, so that they can make a yes or no decision on putting [those policies] into place.”

The youth council, which has been active since 2003, advises Montreal’s mayor and executive committee on issues that affect youth.

“We convey the preoccupations of Montreal youth to city hall and act as a go-between to make sure that the voices of young Montrealers are heard in city hall,” Wiseman said, adding that the council remains independent and non-partisan in its work.

Engaging Citizens

Wiseman said the 2012 student movement and the Occupy movement revealed a “real flourishing of citizen participation” and that much of that engagement was youth-driven.

“However, we haven’t historically seen a lot of that engagement translating into more formal political processes, most of all at the municipal level,” he said.

That’s something the CjM would like to see change in the future. They want the city to open polling places in post-secondary institutions and other areas frequented by young Montrealers. According to the CjM, this would help to bring about a “political consciousness” in younger residents, which would in turn encourage participation in the electoral system.

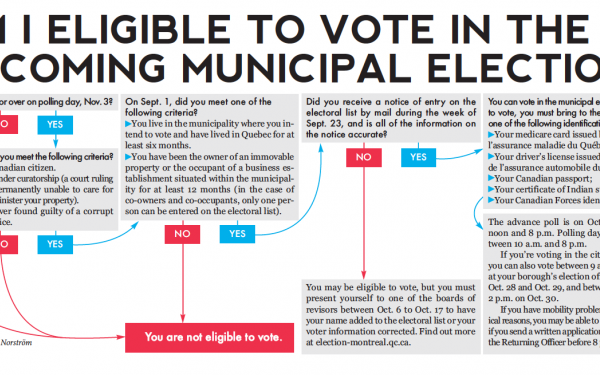

The CjM also wants boards of revisors—the boards you must appear before if you’re not registered on the list of voters, or if there is incorrect information on the notice that you receive in the mail ahead of an election—to make stops in post-secondary institutions like universities and CEGEPs.

Wiseman said young adults move frequently, and the electoral list doesn’t always reflect their changes in address. “It turns into a real hurdle to democratic engagement,” he said.

This is an issue Élection Montréal, which organizes municipal elections in the city, is already taking action on. From Oct. 6 to Oct. 10, there will be boards of revisors at McGill University’s student centre and New Residence Hall, as well as at the Université de Montréal.

Understanding the City

But making it easier for young Montrealers to vote isn’t enough, according to Wiseman. He said a lot of the city’s younger residents lack the knowledge needed to understand how their municipal government works and how they can engage in the political process.

The CjM is recommending that the city, in partnership with Montreal’s school boards, create an educational program similar to Calgary’s City Hall School, which brings students into city hall for a week-long educational program about their government.

“A lot of what we hear back from young Montrealers when we explain not only what we do but also how their city works is, ‘This is the first time I’m hearing that,’” Wiseman said. “There are no citizenship courses out there for most young Montrealers, so they’re growing up […] mostly without any training or knowledge of the institutions that surround them and shape their lives.”

The city of Montreal already has a program for elementary school-aged children, Wiseman said, but “there’s a gap that exists between primary school and the age of voting” since there aren’t any programs targeting secondary schools.

In addition to an educational program for young Montrealers, the CjM also wants local youth councils to be created in Montreal’s boroughs and city documents to be written in a clearer language so that residents can easily understand them.

“In order to encourage engagement, we have to necessarily make sure that [the city communicates] with citizens in a way that’s not only easily understandable, but in a way that’s also easily used and in a workable format,” Wiseman said, adding that he once read a legal notice for a zoning change published in a local newspaper and couldn’t understand it, even though he is fluent in French and has been active in municipal politics.

Wiseman also reflected on promises by some of the candidates running in the election to turn Montreal into an “intelligent” city where people could interact with their municipal administration on the Internet.

“There’s a lot of talk [in the election campaign] of intelligent cities and knowledge cities, but without knowledge of one’s city, it’s hard to see how something like that would work,” he said.

Bylaw P-6, the Environment and Culture

Municipal bylaw P-6 was amended during the 2012 student protests to prohibit demonstrators from covering their faces with scarves or masks. The amended bylaw also makes it mandatory for organizers to provide an itinerary to police ahead of a protest.

The CjM is recommending that the ban on masks be lifted. The youth council also wants another part of the bylaw to be rewritten to clarify the rights and responsibilities of both citizens and police officers during protests.

“It struck us that the amendments to P-6 are likely to hamper youth involvement and youth engagement in their city and their democracy […] more than [protests] would disrupt the city,” Wiseman said. “We ultimately decided that the amendments, as they stand, should be revoked.”

The document published last week also sees the CjM reaffirm its stance on environmental issues, recommending that the city study what public lands could be used for gardening and what land in the city is contaminated.

“There’s a gap in knowledge; we don’t know how much land could be available,” Wiseman said. “So first and foremost, setting up an elementary survey of what [land] there is and what has to be done seemed a logical conclusion to make.”

The CjM is also asking the city to adopt a clear regulatory framework for urban agriculture projects, promote green roofs by providing subsidies or tax returns to those people who install them, and improve public transit while making sure that it remains affordable.

Additionally, the CjM wants the current Accès Montréal program that provides preferential rates to Montreal residents at museums and other cultural venues to be expanded to include a special program for youth. Such a program would make cultural events more affordable, giving young Montrealers greater access to the arts.

The CjM is made up of 15 members between the ages of 16 and 30—six representing the eastern portion of the city, five representing the centre and four representing the west. The council was entrenched into Montreal’s city charter in 2009, making it a formal part of the city’s political system.

For a full list of the CjM’s recommendations, visit the youth council’s website.

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)