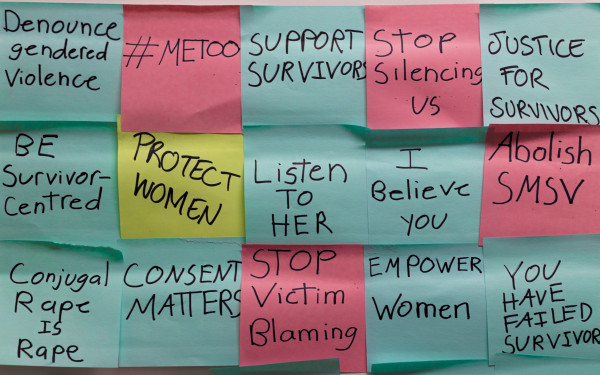

The Freeze Response is Real, So Stop Victim-Blaming

A Little-Known Trauma Coping Mechanism Contradicts our Assault Narrative

“Why didn’t you try to escape?”

“Why did you let them do that to your body?”

“Why didn’t you fight back?”

To this day, survivors of sexual assault still have to deal with these pernicious questions that question the legitimacy of their experiences. These questions show the lack of empathy of the one asking. They also don’t take into account the mental block created by the brain as a defence mechanism when in intensely stressful situations like assault.

The effect is called psychic sideration, but it’s more commonly known as the freeze response. When under attack the body can freeze completely instead of attempting to flee or to fight. It’s a very normal response to traumatic experiences, but isn’t well-known to the general public—leading to questions like the ones above.

Dr. Muriel Salmona, a psychiatrist specializing in sexual trauma and the founder of the Mémoire traumatique et victimologie association in France, explains that this survival mechanism occurs when an individual experiences a brutal emotional and physical shock. The shock causes the secretion of adrenaline and stress hormones in such large quantities that the brain decides to cut itself from reality in order to preserve the vital functions of the individual.

Like an electrical circuit when the current flow spikes, a fuse blows to avoid overloading the whole system.

The state triggered could be considered similar to that of a coma in some situations. The victim becomes completely absent, which makes it easy to manipulate them physically and mentally.

Salmona said in another interview that freezing during an attack will often make it difficult to remember details or a timeline. They disconnect mentally as well as physically, which makes their narrative shaky. This may even cause some victims and listeners to question whether the attack even happened or not.

One big problem is that repeat aggressors often know about the power of this defence mechanism. They will push their victim into this state by trying at all costs to provoke a violent shock.

It is important to understand that a person can remain under the mental effects of the freeze response long after the incident, even months after—especially among children who’ve experienced an assault.

For example, someone who had been raped a short time ago and who seems to be doing well because they do not express any emotion, anger, or fear, can still be under the influence of the emotional detachment implied by the freeze response. Getting out of the torpor caused by the state of intense stress is an arduous but necessary process.

Furthermore, this little-known but very common physical response contradicts our society’s accepted narrative of how a “real” assault plays out. Victims are expected to fight back, call for help, or make attempts to prevent the attack, but the reality is that isn’t how it happens in many situations. This also puts the onus of preventing sexual assault on victims, as opposed to perpetrator where it should be.

So if we want to further eliminate victim-blaming towards survivors of assault, we need to raise awareness about the freeze response.