The Beating Heart of Montreal Jazz

Looking Back at the Rising Sun Club and Legendary Jazz Promoter Roué-Doudou Boicel

On a smotheringly hot mid-1950s day in French Guiana, a teenage Rouè-Doudou Boicel paces impatiently, waiting for his mother to leave the house. She had recently come home with a Luis Mariano vinyl record, intended to be hidden away and eventually offered as a birthday gift to his stepfather.

Once alone, Boicel brings the gift to the local record shop and exchanges it for his favourite jazz album, Dizzy Gillespie’s The Champ.

“Dizzy’s music spoke to me like nothing else before,” he says looking back today. “I loved that album more than anything.”

Nearly three decades later, Gillespie had become a regular performer at Boicel’s Rising Sun Celebrity Jazz Club in Montreal, a bar and music joint he opened on Ste. Catherine St. in 1975.

“After so many years, Dizzy was playing for me, in my club. That beats everything,” says Boicel.

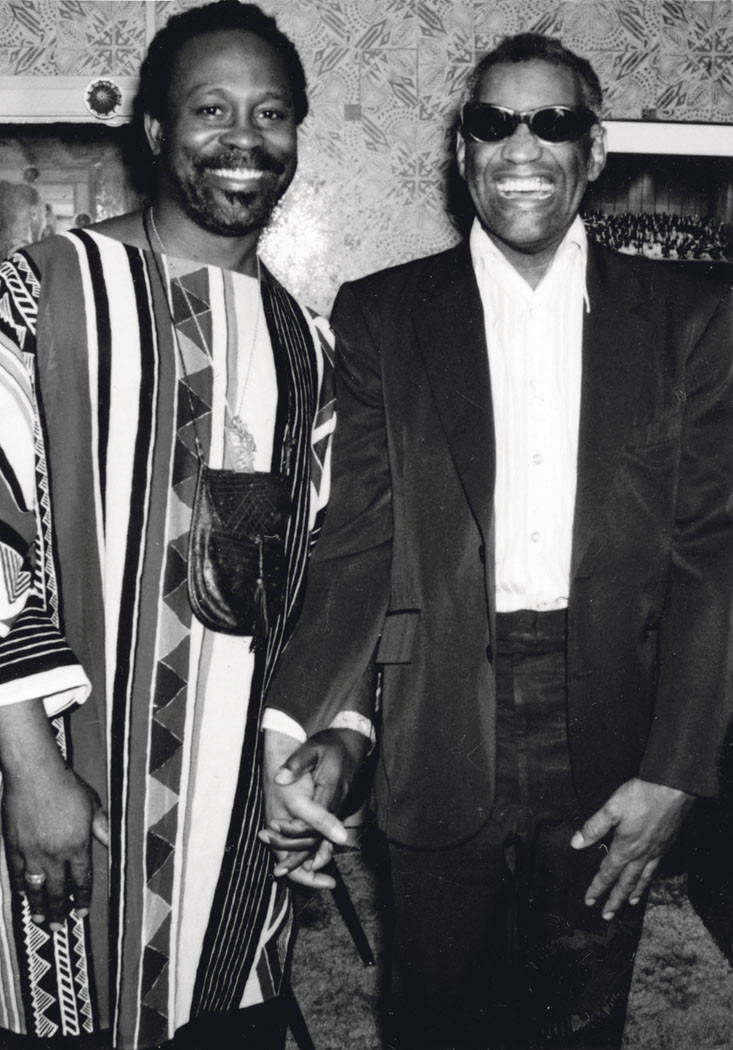

Now 75 years old, Boicel is sitting in the living room of one of his NDG residences, surrounded by scrapbooks overflowing with pictures from his promoter days.

On one page Boicel is shaking hands with Ray Charles; on another he’s posing with Muhammad Ali. In what he calls one of his favourite pictures, he’s flanked by blues greats John Lee Hooker, Muddy Waters and Willie Dixon—all four men bursting with laughter.

“What we had during those days will never be repeated in Montreal,” says Boicel, nostalgia visibly building as he flips through the pages of one of the books.

The Rising Sun’s family-like atmosphere set it apart from other venues in the city at the time, and that atmosphere stemmed from its owner.

“Doudou ran music in Montreal for many years,” says Jim West, president of Montreal’s Justin Time Records, which later released a series of recordings from the club.

“He knew everybody, he befriended them all, and it’s pretty unique to have a character like that.”

Boicel’s passion for music started at an early age, playing bass and the helicon in his pre-teenage years before later picking up the trumpet and conga.

Before moving to Montreal in 1970, he worked a variety of jobs—as a grave keeper, as an electrician, a short stint in the Cayenne military—travelling across Europe and eventually to North America.

His arrival in Montreal wasn’t supposed to be anything more than another stop along the way, but Boicel quickly fell in love with the city’s free spirit in the early ‘70s and decided to stay. He had witnessed the jazz and blues scene present in Harlem during his last stop before Quebec, and thought the same type of scene could thrive in Montreal.

“The Rising Sun opened at the same time that jazz music was disappearing from the musical scene, but I knew it wasn’t dead,” he says.

He was right, and within a few years of its opening, the tiny club was regularly packing more than 300 people into a space made to hold no more than half of that for shows by some of the era’s greatest jazz and blues performers.

Boicel made it a point to promote black culture within the city, and it wasn’t long before his reputation as one of the only black promoters around helped him land some of the period’s biggest names.

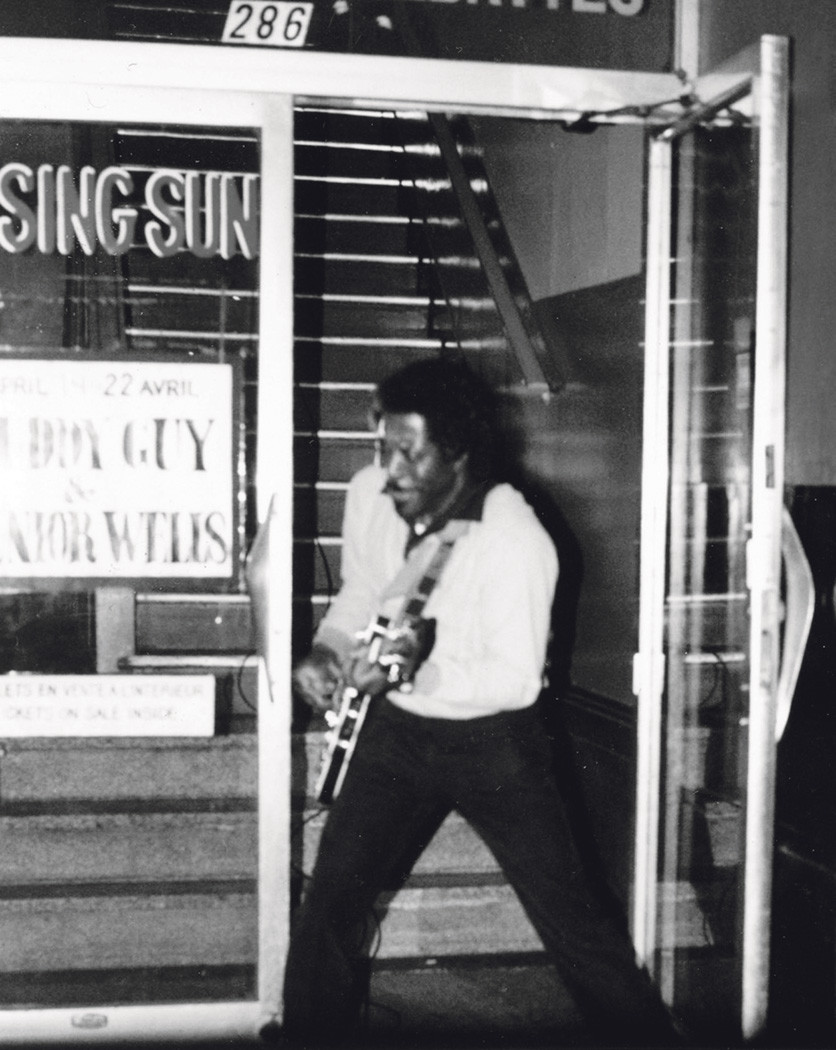

In the summer of 1978, two years before the inaugural Montreal International Jazz Festival, he founded a festival of his own called the Rising Sun Festijazz, featuring a set by acclaimed guitarist B.B. King.

When King returned to Montreal and played at Place des Arts the following year, he spent the rest of the night across the street at the Rising Sun.

“He came here afterwards, took off all his fancy clothes and played until five in the morning,” recalls Boicel. “And the fans that followed, they would be here, ripping their jackets off and swinging their ties in the air.”

Year by year, the Rising Sun started harvesting a reputation as a must-play place.

“His club was like Paris in the ‘30s, New York in the ‘40s,” blues legend Taj Mahal says over the phone from Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

“It was a crossroads of all kinds of music. The atmosphere was so good because he attracted a very musically excited audience—poets, singers, dancers,” he says.

Dave Turner, who teaches at Concordia and has been a mainstay of the Montreal jazz scene since the early ‘70s, sat in with Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers a few times at the Rising Sun.

“It was a life-changing experience to play there,” he says.

“You can’t really know if you’re at that level until you play with people like that. And Boicel was a big inspiration to a lot of people for being able to bring those acts to the city.”

His club was like Paris in the ‘30s, New York in the ‘40s. – Blues legend Taj Mahal

Boicel himself had become somewhat of a public figure in Montreal.

“People would come to see both the artists and him,” says his son Alex, now a promoter in his own right based in Harlem.

“He would dress like an African king and it became part of the mystery for people,” he says. “As his son at the time, it wasn’t always so easy to deal with him. For me, it was not only the Rising Sun, but it was also Doudou who was rising.”

Later, in his home office, Boicel starts pulling out letters from an old filing cabinet, all of them acknowledging his contributions to the culture of Montreal.

The first is from former Montreal mayor Gérald Tremblay, followed by others from former Quebec premier Jean Charest, former governor general Michaëlle Jean and Prime Minister Stephen Harper.

As he opens a fifth letter, he bursts into a loud, raspy laugh.

“This girl, I tell you,” he says with a smile draped across his face, the same one seen in all of the pictures from so long ago.

It’s a letter from 1995, penned by Jazz singer Nina Simone and containing about as much character as any one-page letter can hold.

In it, she jokingly asks Boicel for $10,000 of royalties to be sent to her address in France “for every month until you die.”

“‘A queen like me is very expensive, I’ll hunt you down,’” Boicel reads from the letter, breaking out into a chuckle.

“She called me after that letter and we laughed for hours,” he says.

In 2003, eight years after that letter was sent, Simone died in her sleep after a long battle with breast cancer.

“It hurts, it really hurts,” he says, no longer laughing. “All these artists I’ve lost, I really loved them. We were all part of the international jazz family.”

The original Rising Sun burned down in March of 1990. At the time, the closest fire station was nearly 20 minutes away on Ontario St., and in the time it took the firemen to respond to the call, nearly everything was gone. The stage had been destroyed and hundreds of concert recordings were lost.

Boicel tried twice to reopen the club at different locations, but could never quite regain the feeling and atmosphere of the original. The third incarnation closed only a year and a half after opening and left him $100,000 in debt.

Since then, Boicel has focused his time on writing and painting—the recent student protests inspiring both—as he prepares to release his third book this summer, a collection of poetry and essays.

Two days after the incident that ruined the original Rising Sun, he tried to salvage anything he could from the wreckage. In what he now calls a miracle, he was able to save a few concert recordings that had been stored away in an old defunct freezer.

For Boicel, those recordings, his pictures and his many memories are all that are left of the Rising Sun today.

“I would do it all again like this,” he says, snapping his fingers together, a smile inching back across his face as he revisits those days that loom so large in his memory.

“Of course I would.”