Special Issue: Jail of My Ancestors, Shame of Humanity

The Story of Gorée Island

It’s half past noon. The sun is burning. I almost missed the boat to Gorée Island. Two minutes ago, I was stuck in a chaotic traffic jam in the big city of Dakar. I found a seat in the crowded boat.

Most of the passengers are craft makers coming from every part of Senegal with bags full of pieces of art that they will try to sell to visitors from abroad. Today, however, there are fewer tourists because of the recent conflict with neighbouring Gambia.

1_672_1050_90.jpg)

While approaching the island, I can’t stop thinking about my ancestors that had that same view. They came with the useless hope of, one day, returning to the land that gave them life. Instead, they left disoriented, broken, arms and legs tied up with rusted chains.

While awkwardly stepping onto the dock, avoiding to fall in the gap, two strong men pull me off the boat. Here I am, feet in the warm sand, on the very land where, five centuries ago, my ancestors were brought and shipped, stolen.

The cool breeze is refreshing. Though I am somewhat dizzy, a feeling of well-being takes over my body. I feel surprisingly calm and happy, seeing the colourful fishing boats lying on the beach. Yet, I am here to see and understand what my ancestors endured when being forced into slavery.

As I start my visit, I am distracted by a strange painting on one wall. Ancient sailboats transforming into a long arched bridge. Under the painting, I read, “From whence we came, we now return.” Though I cannot yet say why, I strongly feel included in that “we.”

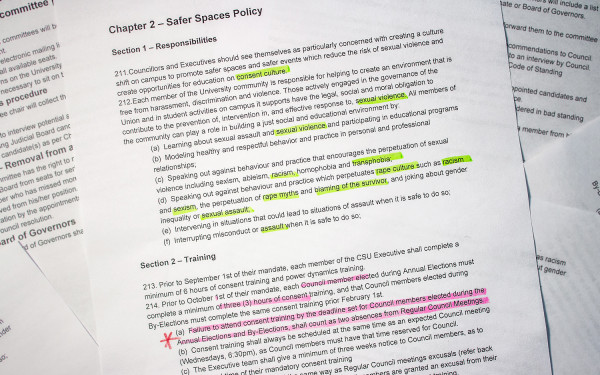

2_788_1050_90.jpg)

Walking through the narrow alleys of the small island, I am surrounded by colourful houses. Local artists paint on the street. Their art is exposed and sold all around the island.

Since becoming a UNESCO world heritage site in 1978, Gorée has become a must-see for tourists visiting West Africa: Europeans who want to make peace with history, people, like me, of African descent who wish to come back to their ancestors’ lands, or anyone who is interested in this side of our humanity.

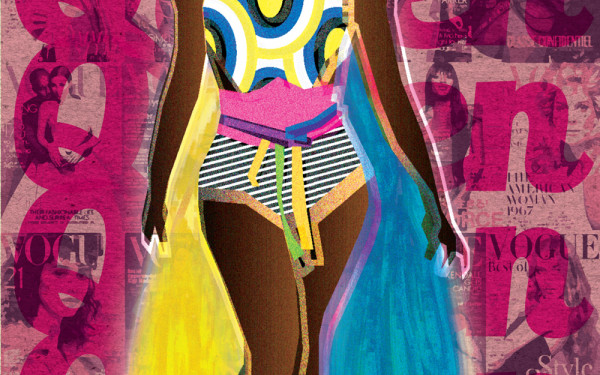

As I am standing in the centre of the House of Slaves, I feel a pressure on my chest.

I think of my grandparents’ grandparents who were born into slavery. All around me are the cells that held captive millions of children, men and women while they waited to be shipped to the unknown.

I enter another room where, dozens of young girls, half my age, were crammed into a tiny concrete room, naked, and deprived of all dignity. Separated from their parents, they were offered to buyers seeking virgin flesh. It was the only room with some kind of a latrine.

A simple hole in the corner “guaranteed” that customers would not feel inconvenienced. The other cells were even smaller. Women were separated from men, children from their parents, the healthy from the sick. The latter were given to the sharks waiting behind the door.

In front of me is this door. The famous “Door of no return”—La porte sans retour—through which millions of Africans boarded slave ships by force, taking with them only memories of their homes, lives, and loved ones. I can’t describe all the turmoil I am feeling in this door frame.

No book nor documentary compares to walking in my ancestors’ footsteps.

My ancestors were part of one of the most horrible chapters in human history. My father belongs to the oppressors’ ethnic group, while my mother is of direct descent of the oppressed.

Whether or not my ancestors physically went through this door—not all slaves stepped on the island—to me the door symbolizes the immense suffering and cruelty that occurred from the 15th century to the 19th century and beyond.

No book nor documentary compares to walking in my ancestors’ footsteps. Outside of the House of Slaves is the Statue of Liberation. This massive sculpture, given by France in 2006, is a symbol of the abolition of the slave trade and the reconciliation between nations.

3_818_1050_90.jpg)

Here in Gorée, life continues. Fatou Seck, one of the island’s merchants says, “It’s sad, but it’s history from the past. We have forgiven them all, but we will never forget.” I realize that her perception of that period is different than mine.

The people of Gorée, today, are the descendants of the ones who stayed. Racism as we know it in America and the burden of slavery, segregation, and mass incarceration still existent in our lives, is not present here.

The suffering of the African people has been and is different. They have seen their rich country being invaded and stripped away of its natural resources. This is why their inhabitants became, for some, amongst the poorest on earth.

Referring to the Door of No Return, Alpha Oumar Diallo, a sociologist from Dakar, says, “It was a door without return but today it is a door with return […] They thought they would never come back, but today they are coming back through their grandchildren […] like you.”

Sarah Bourbonnais, a Canadian tourist sitting next to me on the way back to Dakar, told me that she finds it imperative to bring along her young son, whose father is Senegalese, “so he can withstand racism and understand the power of his heritage.”

The metaphorical painting of ships transforming into a long bridge now fully makes sense to me.

7_900_366_90.jpg)

5_900_207_90.jpg)