Second installation of the Indigenous Forced Displacement project displayed at MIND high school

Photographs of Indigenous community members are a reminder of resilience and pride

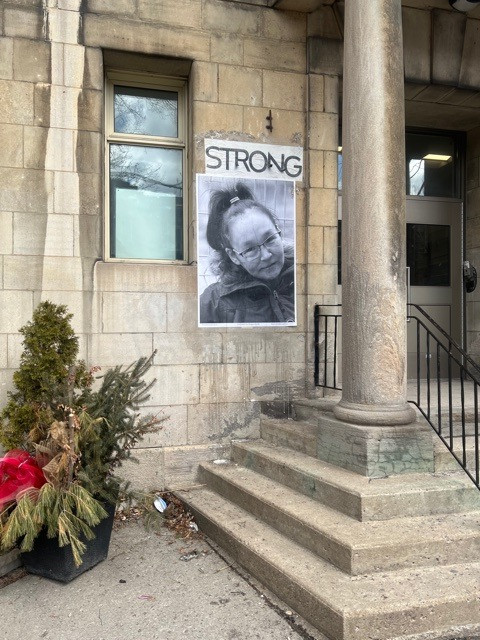

Portraits of members of the Montreal Indigenous community were pasted on the outside of MIND high school and near the Jean-Talon market on Mar. 21.

This is the second installation of the Indigenous Forced Displacement project organized by Nakuset as part of the Inside Out project. She worked with photographers Craig Commanda, Vicki McDonald, and Martin Loft, as well as the students from MIND high school who helped put up the portraits.

The Inside Out project is a worldwide participatory project founded by French artist JR with installations in over 138 countries. Individuals and communities can make a statement by creating an “Action”. These are what Inside Out calls their group initiatives which tackle a range of topics such as diversity, community, racism, and education.

Nakuset said she applied after looking at the Inside Out website and noticing there weren’t many Canadian Indigenous projects.

The first installation of the Indigenous Forced Displacement Project went up on Feb. 20 on buildings around Montreal. The goal of the installations is to use portraits to bring awareness to the resilience of Indigenous peoples in the face of forced displacement.

Read more: Photography exhibition looks to accurately rewrite history

“The thing is that we’re kind of like an invisible society,” said Nakuset. Before she started working with the students who helped with the project, Nakuset gave them a history lesson. “We know about residential schools, the Sixties Scoop, we know about mass graves, and this whole project is the fact that we’re still here.”

“The pictures of the children, that’s our future. Warriors.” — Nakuset

In an interview with The Eastern Door, Nakuset said taking photos was the easy part, but deciding where they were going to go up was a challenge. A press release was sent out months before the first installment asking the community to step up and offer a building. The request for buildings continued to spread on social media. After the first installation, people saw the effects of the project and started offering buildings. “What we want is very visible places, we want people to walk by and see it and people to get a reaction when they see it,” said Nakuset.

She also said there’s a lot of thought that goes into curating the images. Nakuset tries to arrange the photos to create a sense of togetherness. For example, a photo of a little girl will be put beside a photo of an elder for a sense of safety, and cousins are grouped together.

This second installation was the first time words were incorporated into the display of the portraits. Students came up with a descriptive word about each person and paired them with the images. “People will see the title and think ‘Wow, that is a strong woman, [she] is resilient,’” said Nakuset. “The pictures of the children, that’s our future. Warriors.”

This project was Commanda’s first time shooting portraits. He said he enjoyed it because he was able to connect more to the subject in a way that other types of photography don’t really allow. To make the subject more comfortable Commanda said he usually starts by making a few jokes about the situation.

“I’ve always found [humour] to be very beneficial in bringing people together and making connections happen,” said Commanda. “If we were serious all the time I think we would be a lot more miserable.”

McDonald, whose work was also featured in the second installment of the project, said she feels pride when she sees the photos. “Even with everything they experienced in their lifetime, the pain and the trauma, look how they smile, look how beautiful and resilient they are,” said McDonald. “Each person I spoke to has such a magical soul.”

One of the portraits that went up in the second installation was a man named Victor, who was a CBC actor when he was younger and also a survivor of the Sixties Scoop. “When you have a conversation with him it could last hours,” said McDonald. “He has so much to say and is such a brilliant man.”

Nakuset said it’s really hard to say how people will react when they see the installation, however, she hopes individuals will take action based on what they do best. “Maybe if they’re inspired by it they can start their own project, or maybe because it’s an Indigenous issue, they can volunteer at an Indigenous organization,” she said.

McDonald feels the impact of this project makes people feel seen. “[I hope people feel] seen in a different light. It’s not all negative. It’s beautiful. Everybody has so much beauty.”