Photo Essay: Neither Here Nor There

A Look Into the Boxed in Ville Saint-Pierre

The neighbourhood of Saint-Pierre is an enclave.

Photos by Chris M. Forsyth.

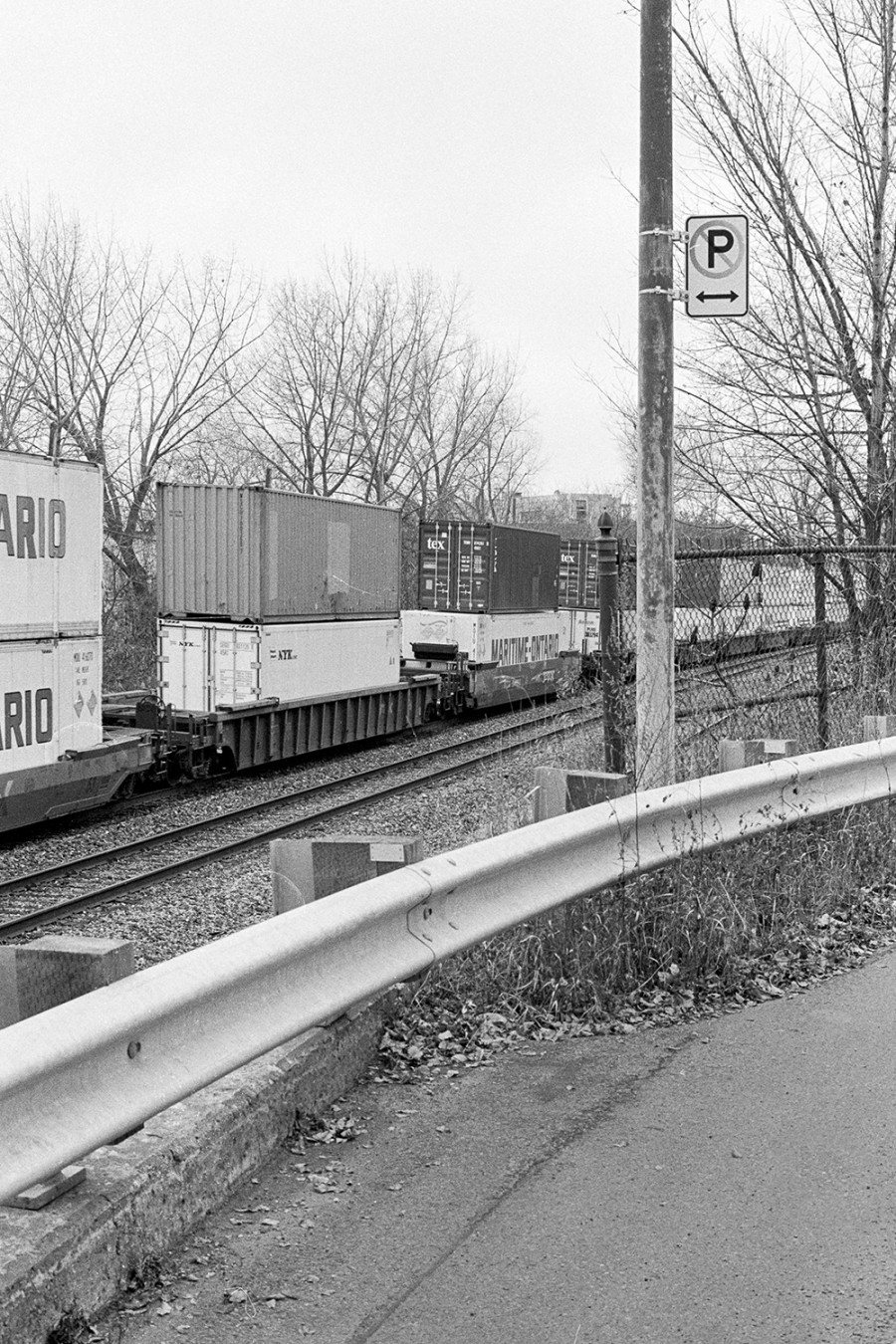

As urban development sprawled westward from Montreal’s core, the once economically and politically independent village became boxed in—closed off by a Canadian National railway to the west, highways along its southern border, and a hill to its east. It’s physical capacity is confined by these immovable and imposing structures, and without proper planning, so are its residents.

In the 15 years since the neighbourhood officially became a part of the city of Montreal, Saint-Pierre’s approximate 5,000 residents have become increasingly limited by what remains within these borders. In recent years, local essential services have dwindled, leaving the population particularly vulnerable. One group hopes to change that.

A sign on Des Érables St., known by many as Devil’s Hill, welcomes passers-by into the Saint-Pierre neighbourhood of Lachine. Until 1999, Saint-Pierre was its own village. The name Ville Saint-Pierre for many has stuck, despite the fact that it has since become a part of the Montreal borough of Lachine, on which it is economically dependent.

About 5,000 people live within the less than one square kilometer that make up Saint-Pierre. But 40 per cent of those residents move away every five years, said Isaac Boulou, the project lead for Revitalisation Saint-Pierre. Boulou’s group has been working with the municipal government to solve some of the area’s biggest problems since 2003. Forty per cent of Saint-Pierre residents are also considered to be low-income.

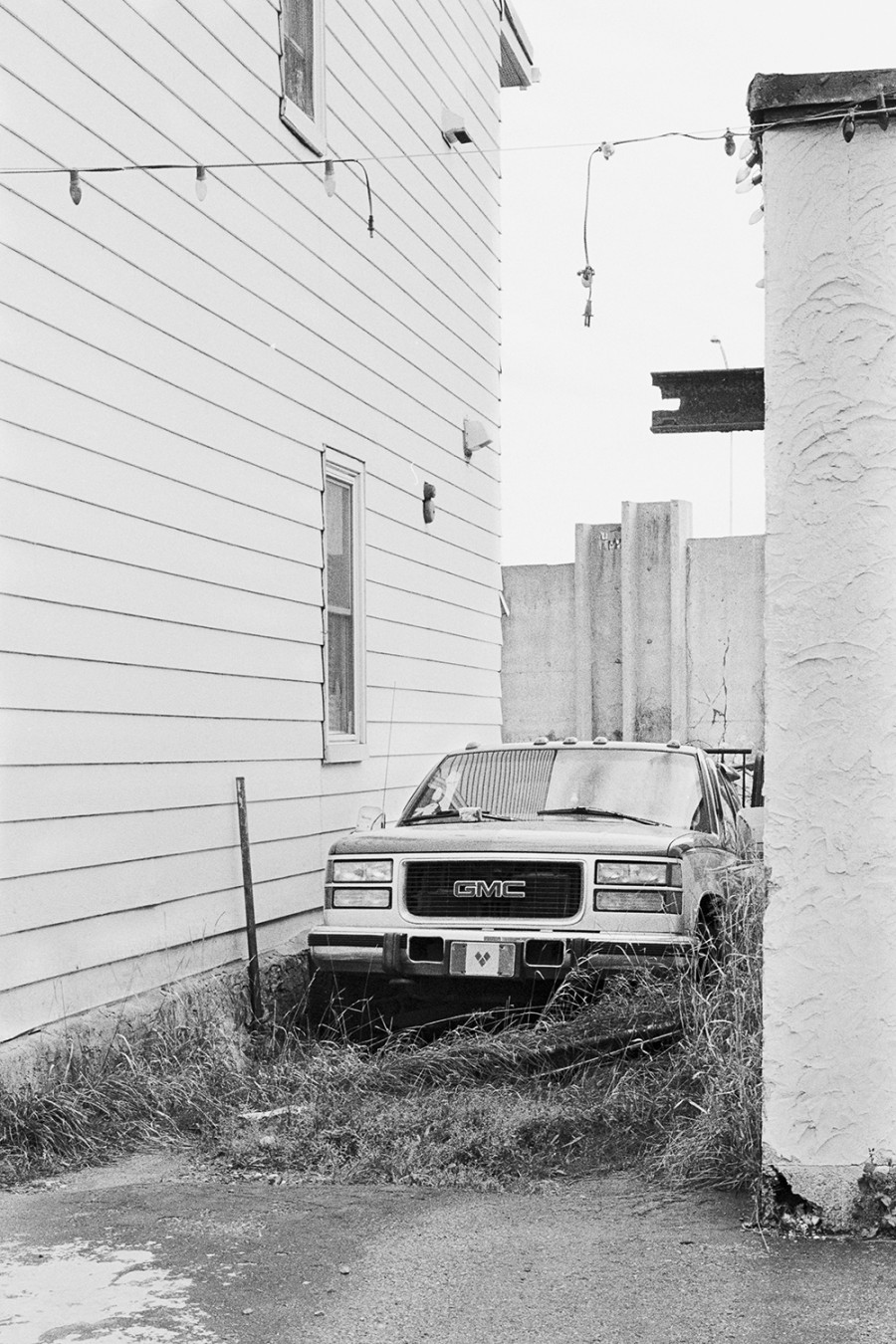

Some of the homes that sit along Saint-Pierre’s southern and eastern border, like this one on Richmond St., are decorated with billboards, aimed at the drivers who travel along Highway 20 and through the Saint-Pierre Interchange. Because of the neighbourhood’s proximity to the major autoroutes, noise and air pollution are a serious problem for residents, explained Bolou.

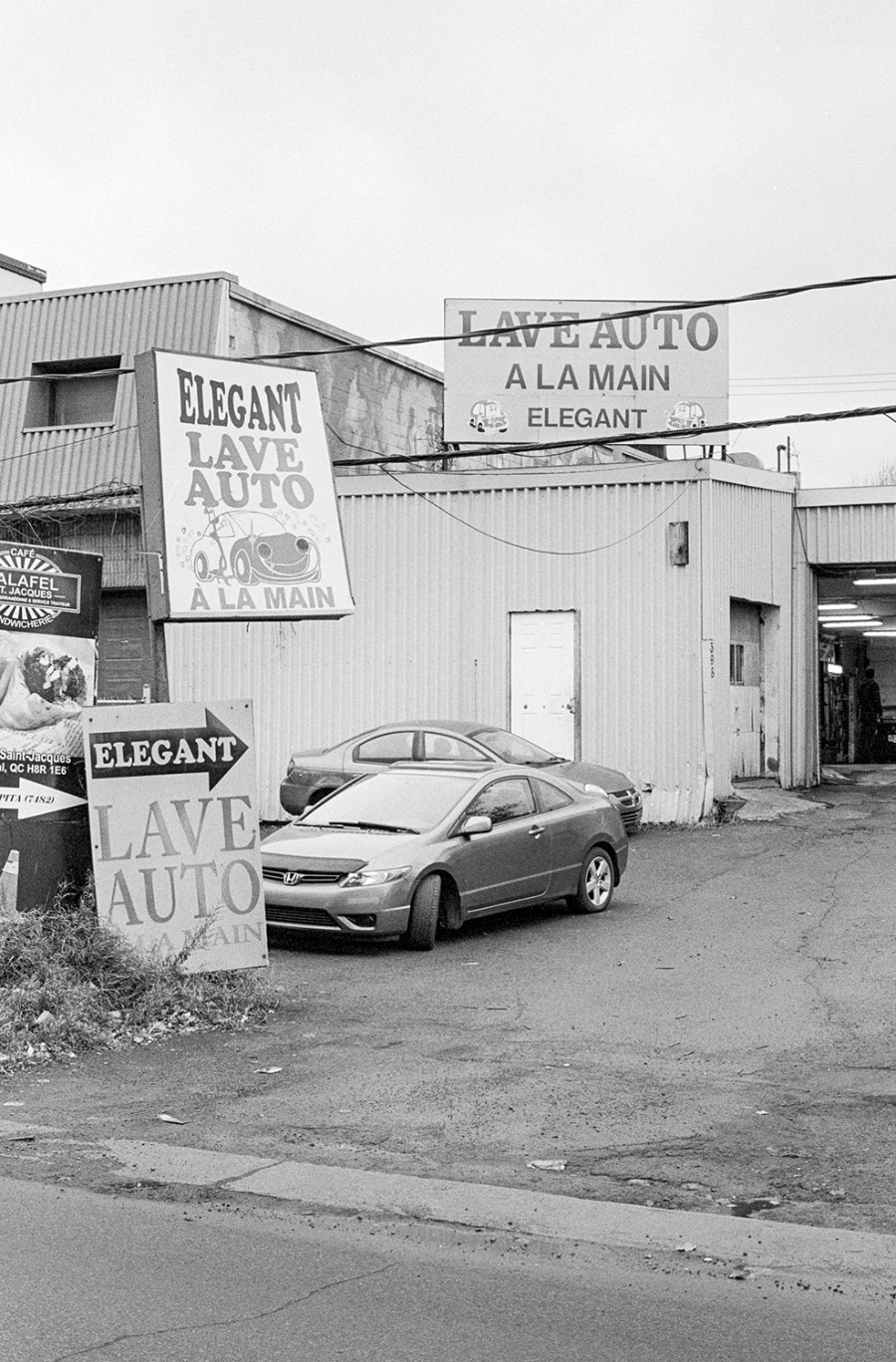

Over the last two decades, Saint- Pierre has continued to lose local businesses, explained Boulou, who also lives in the neighbourhood. In June, the last bank in the area, Caisse Desjardins, closed their sole remaining ATM—the branch itself had closed in October of last year. The only ATM in Saint-Pierre is in a depanneur, much like this one sits on the corner of Des Érables St. and Saint-Pierre Ave.

Due to its proximity to one of Montreal’s major highways and the city’s near-constant construction, many commuters opt to travel through Saint-Pierre’s main artery, Saint-Jacques St., to bypass the almost-certain traffic. Bolou explained that 12,000 cars travel on Saint-Jacques St. daily. The problem, he continued, is that Saint-Pierre is a village and its roads aren’t built to sustain such frequent use, especially by trucks that use the alternate route.

“The state of urban planning in Saint-Pierre needs to be reviewed completely,” said Boulou. “Environmentally, as well as economically and socially.”

“It becomes a matter of public health,” he continued.

The increased road traffic contributes to an overall rise in temperatures in Saint-Pierre, Boulou said. A heat map put together by the government of Quebec’s Institut national de santé publique in 2015 depicts Saint-Pierre as being among the hottest recorded areas on the island, compared to the municipality of Montreal West, which borders it and is significantly cooler.

Boulou calls disappearing industry and business a contributor to Saint-Pierre’s problems. Used car part centre, Vincent, on Vincent Ave. is an anomaly for the area and has remained in business for the last 70 years.

“There are a lot fewer options and less services [for local residents],” he said. There used to be a large grocery store, but when that closed, those who lived in Saint-Pierre were left with nothing. One of Revitalisation Saint- Pierre’s larger successes was the opening of a new market, Marché Saint-Pierre, in June 2010.

But still, he said that Saint- Pierre’s streets aren’t welcoming for pedestrians, which impedes residents from visiting the stores and restaurants that still stand in the neighbourhood.