Art Review: The Complicated Legacy of the Western in the Musée des Beaux-Arts

How the Exhibit Could Have Done Better

“The West – the very words go straight to that place of the heart where Americans feel the spirit of pride in their western heritage–the triumph of personal courage over any obstacle, whether nature or man.” — John Wayne

Upon hearing about the ambitious project that was undertaken by the Musée des Beaux-Arts to present a major multidisciplinary exhibit of the Western film genre, I had mixed feelings.

It is true that the artistic achievements of the Western and the art it formerly drew inspiration from—and has subsequently inspired—are vast and far reaching. Yet it is also an area that deserves a lot more attention and unpacking concerning the assumptions that inform its origins.

When I approached the entrance of the exhibit—entitled Once Upon a Time… The Western: A New Frontier in Art and Film—I observed a gift shop that was replete with mass-produced moccasins on my right, and a children’s play room which featured an impressively staged Western backdrop complete with cacti, plush-horses, and a wall full of dress-up cowboy hats on my left, my apprehension was kicked into high gear.

To introduce the subject, the exhibition presents the earliest images we have of the west by the west. With Buffalo Bill front and centre, the viewer is treated to a series of panoramic landscapes glorifying the geological disproportion and the immensity of the American territory.

The section offers an impressive collection of artists such as W. Herbert Dunton, Charles Marion Russell, Albert Bierstadt, Thomas Moran, Alexander Phimister Proctor, and Frederic Remington.

In terms of production, it is certainly up to standard with the other blockbusters put forth by the museum, and as the show continues, the choice of work presented does reflect a nuanced appreciation for the dialogue between fine arts and cinema.

We get everyone from Ingrid Bergman and Sergio Leone, to Jean-Pierre Lefebvre and Quentin Tarantino. From a filmmaker’s perspective, it is a treasure trove of subtle reference and inspiration, accentuated by groundbreaking editing and sound.

Even from a purely visual point-of-view, the curatorial choice to present abstract expressionist paintings in the room following stills from John Ford and Sam Peckinpah is not lost on the viewer. Although it was a dynamic and aesthetically challenging display in many respects, I was left feeling that, conceptually, the exhibition bit off more than it can chew.

After all, this exhibit is not marketed towards those with an eye for depth of field and focus, and a keen understanding of the complex socio-economic realities that these expertly lighted frames contain. It is being marketed towards families, children, tourists, and to a general public that isn’t always going to absorb these challenging images through the lazy ironic lens they are supposedly being filtered through.

Eric Clement writes in an article for La Presse that the exhibition is, “dynamic, very visual, nourishing, it is addressed to the children of today as to those of yesterday who played so much to ‘Indians’ and ’cowboys’ […] Western film lovers will be delighted: it offers no fewer than 150 excerpts of films!”

I could say a lot about the problems with this praise, but first, a quick disclaimer: I don’t underestimate the intelligence of the public regarding our country’s history. While wandering through the exhibit, I overheard a mother explaining to her young son the falsity present in an image depicting an Indigenous chief and Western explorer happily shaking hands at their supposedly peaceful meeting. Or rather, I heard her trying to explain, clumsily suggesting to her five year-old that he should not take the picture at face value.

I applaud her for having the patience to try, but let’s be honest, how would you explain this situation to a child, against the contrast of the artistically stunning yet deeply racist account of history?

These images contain incredibly complex issues. Capturing our modern liberal consciousness in all its contradictions, the difficulty of power dynamics is what should be the central focus of an exploration into how the West has been presented within North America and elsewhere.

It is true that the Indigenous reality and perspective are present in the first part of the exhibit, with naïve Cheyenne, Lakota and Arapaho drawings of the nineteenth century that relate the battles between “Whites” and “Indians,” but they are simply not the focus of what is being shown.

One thing the show does expertly reveal is how art has the power to both maintain and challenge these widespread beliefs and stereotypes. The question remains as to where this specific collection of work falls on that spectrum. Despite grand claims in the accompanying texts, I just don’t think this show pushes back hard enough against the story it claims to problematize.

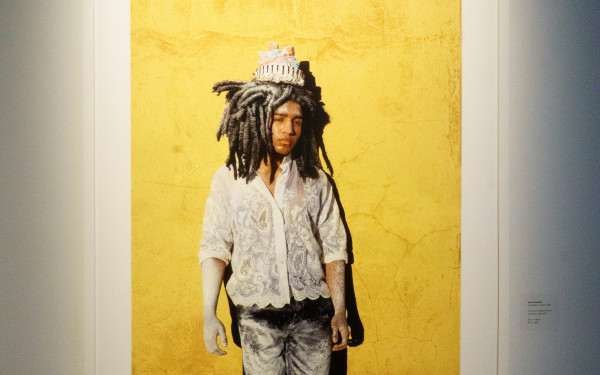

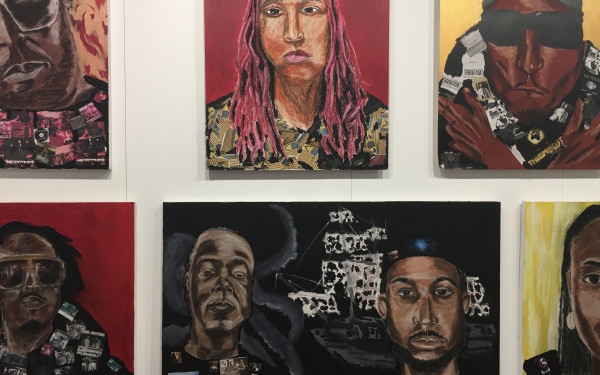

Sure, the exhibit ends with some extremely provocative counter-narratives, and the work of Indigenous artists such as Kent Monkman, Wendy Red Star, Biran Jungen, and Adrian Stimson provides some powerful material that I just couldn’t help feeling would be better received in a different context.

In the five rooms leading up to the end, we primarily have work that—regardless of its potentially subversive aspirations—reinforces the Western myth. In order to deflate this, a few throwaway quotes have been painted in white on the maroon walls, as if to reveal the true, yet mysteriously elusive, intent of the creative geniuses who produced the material before us.

The problem is that the fascination, creation, dissemination, or prevalence of the Western myth is not something that can be adequately addressed by a few poignant sentences juxtaposed against multiple images of violence, Indigenous men raping white women, dignified European pioneers, and so forth.

Simply labeling something as difficult doesn’t necessarily prevent the images from having a profound and lasting impact on the viewer. Especially if that viewer is unaware of the circumstances surrounding the production of that image and its current supposed “re-contextualization.”

Presenting these images in a prominent space under expert lighting in a private institution that is built on the traditional territory of the Kanien’kehá:ka people, and charging viewers $22 for admission is a perfect example of awkward cultural phenomenon worth examining in and of itself.

“The cinema is not a factory of dreams, it is a factory of myths,” said renowned Western film director Sergio Leone. Maybe this quote should have been the springboard rather than an afterthought painted high on a wall, inaccessible to the young porous minds which will make up a sizable percentage of the demographic who will frequent this space during the coming months.