MONUMENT: A 91-page Love Letter to Mumtaz Mahal

Manahil Bandukwala’s Debut Poetry Collection is Modern and Assertive

In her debut poetry collection MONUMENT, author Manahil Bandukwala weaves a 91-page love letter to Arjumand Banu, dedicating every poem to her muse.

Popularly known as Mumtaz Mahal (The Chosen One of the Palace), she was one of five wives of Shihab-ud-Din Muhammad Khurram, more famously known as Shah Jahan, the Mughal Emperor of India in the early 17th century. Her husband gave her the name of Mumtaz Mahal to show she was his favourite wife.

When Arjumand died, Khurram commissioned the construction of the Taj Mahal to serve as his wife’s tomb. In her book, Bandukwala provides an empowering retelling of Arjumand’s life, which ended abruptly at 38 years old following the birth of her 14th child.

Khurram’s reign was marked by a hunger for power and expansion. In MONUMENT, Bandukwala explores this duality with her skillful use of imagery and compelling poetry when delving into themes of death, power and beauty.

Though Arjumand died just three years into her husband’s reign, her legacy was one of kindness and compassion. According to historians, she used her influence over the Mughal empire to promote humanitarian programs for vulnerable and underprivileged people.

Bandukwala, who was born and raised in Karachi, Pakistan, wrote MONUMENT while she was completing her Bachelor of Arts in English at Carleton University. It was published in September 2022 by Brick Books.

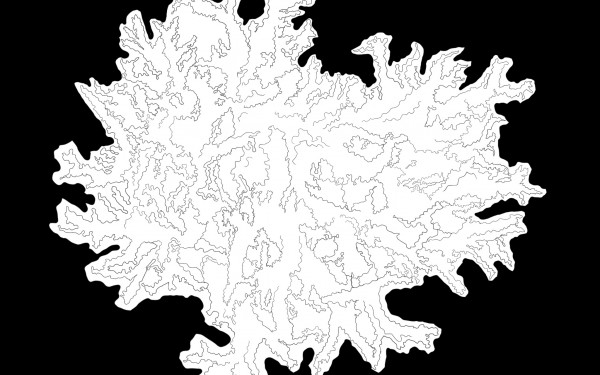

Carefully constructed, the book is divided into eight sections: the prologue, BRAID, LOVE LETTERS, OFFSPRING, THREADS, UNRAVEL, LAST WORDS and PLAIT. Each section ends with an illustration of the Taj Mahal hanging upside down from the top of the right-hand page.

The first drawing illustrates the mausoleum intact beside a poem that starts with the line: “If love is a mausoleum, tear it down // brick by brick […].”

Every subsequent drawing shows the Taj Mahal crumbling more and more, until the last one is simply a pile of bricks at the bottom of the page. This visual element gives Bandukwala’s already potent imagery an even stronger presence.

The poem “Restart” uses the allegory of an island from the video game Animal Crossing to describe the construction of the Taj Mahal in a sinister, almost macabre way. Bandukwala vividly describes the changing of seasons, the withering of apple trees, the wilting of carnations and “fields teeming with crickets.”

Hints of death lurk throughout this poem and permeate the book as a whole. The ending of “Restart” is especially poignant and hints at anger for Arjumand’s inhumane burial.

Bandukwala uses MONUMENT to describe how Arjumand’s final resting place was anything but peaceful. In the poem “Petrify,” the poet recounts how the empress’ “body did not decompose into dust / but began a slow petrification.”

The same poem compares Khurram to Medusa and shows how he robbed his wife of a dignified death. The final two stanzas are almost even more impactful than the aforementioned couplet:

“soul squeezed out of the tips

of your marble fingers,

you are alone, the incorporeal

part of you the texture of stone.”

Bandukwala also writes powerfully about empire. “1628,” a love letter Bandukwala pens to Khurram in Arjumand’s voice, opens with the words: “On your back I kissed empire then / smudged it off, tasted dirt on tongue tip.” The result is a bitter commentary on the emperor’s abuse of power throughout his rule and how Arjumand was powerless in their relationship—an important undercurrent in MONUMENT.

The final two stanzas of “1628” are especially poignant:

“[...] I bit the word off your bicep

but you had it tattooed below skin.

I could brush it off myself, but you—I could not

dust you off.”

In all, MONUMENT is a resounding expression of frustration with Arjumand Banu’s fate. Bandukwala offers insight into a rich historical period without sacrificing any of the work’s poetic qualities.

There are elements of Arjumand’s rich life that could have been elaborated on. An exploration of Khurram’s four other wives, for instance, is lacking. Bandukwala does, of course, mention that the empress lived with these women, but readers never learn their names or how they might have felt about Arjumand being Khurram’s favourite.

Doing so might have given readers more insight on Arjumand’s influence and provided agency to these other wives, though it might also have taken away from her narrative being reclaimed. In terms of reclaiming a legacy reduced to stone, as Bandukwala writes in “Monsoon,” this book is entirely effective.

This article originally appeared in Volume 43, Issue 11, published February 7, 2023.