Mental Health Support lacking for MENA Students

Universities dangerously neglect MENA students’ mental health

Disclaimer: The interlocutor interviewed in this piece will be referred to with a pseudonym to protect their privacy.

“Mental health resources were not advertised, they were just there,” is what a Muslim Syrian undergraduate student from McGill University told me when I asked about the availability of mental health resources for MENA (Middle Eastern and North African) students. When initiating this conversation with Alma, I did not expect to be surprised.

As a Welsh-Algerian student, I am accustomed to the disillusionments and rejections the healthcare system has to offer MENA patients. However, Alma’s experience as a Kurdish Syrian student impacted by an ongoing string of genocides in the Middle East—the genocide against the Kurds and the genocide against Palestinians in Gaza—served as an important reminder for myself. Adequate mental health support for MENA students remains a distant reality across Montreal universities. Universities are making sure that there will always be a MENA student worse off than I am.

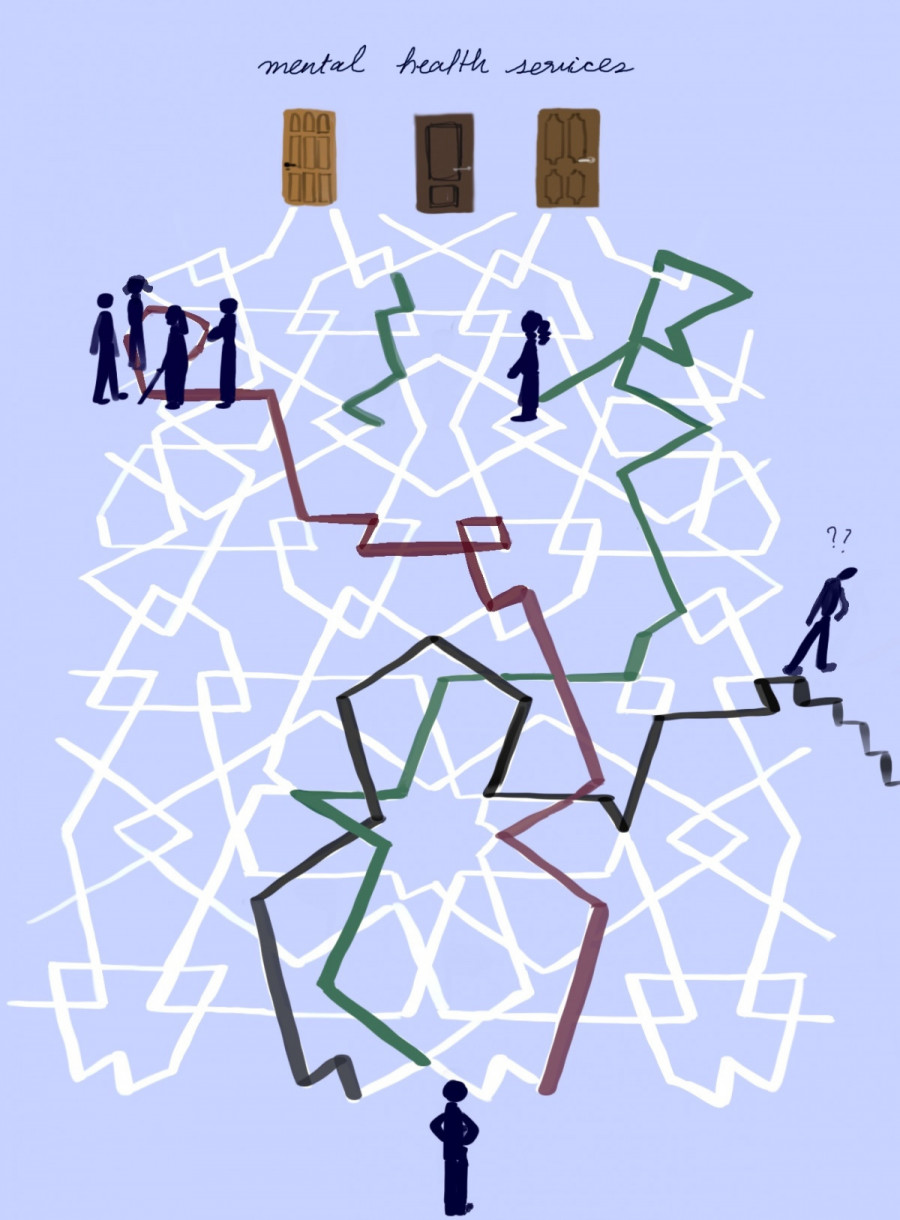

This remark was in reference to the advertisement of general mental health resources, an already bleak show of minimal effort. McGill University’s Student Wellness Hub may offer mental health support resources, but the process of successfully accessing such resources feels more like the stress of an intense competition. This competition offers the winner somewhat adequate health services, and the loser is left stranded, neglected and forced to navigate deteriorating mental health alone. When researching the issue, I came across a post in the r/mcgill subreddit, the comments under which address the very same issue of competition. This post tackled the broader quality of the Wellness Hub’s services, if the average student must compete for an appointment and complains about doing so in the relative anonymous security of a Reddit post, one can only imagine the inaccessibility of mental health support for MENA and other racialised students.

As the conversation unravelled, the experienced access to targeted mental health support for MENA students seemed to deteriorate rapidly.

Gen Z is often said to be the most aware of the importance of mental well-being, but it seems that mental health support stops at political boundaries, in particular ones involving marginalized communities.

The reason for this can be found in popular media’s use of simultaneously sensationalist and reductive vocabulary, diminishing a severe human rights issue to a standard historical conflict. Mental health is also a human right. It is time to start humanising university mental health resources.

Alma recurrently described their experience with the lack of MENA-targeted mental health resources as “exhausting.” Upon successfully navigating McGill’s arguably overwhelmingly complicated Wellness Hub, Alma was disappointed by the lack of diversity in counselling staff. This raises ethical questions concerning the Wellness Hub’s hiring process, but also for MENA and other ethnically diverse students who, in turn, are forced to educate their counsellors on their cultural context. Alma once again described this experience as exhausting. “Having to explain yourself, without focusing on the [mental health] issue” effectively nullifies the purpose of counselling.

This feeling of exhaustion is further exacerbated when the scenario in question is the genocide of Palestinians. This is because Palestinians have strong ties not only within their own community but also with other groups in the Levant region and the broader MENA diaspora. These communities are reminded daily of their collective suffering, deepening the impact of their grief.

Alma felt that the lack of prioritisation for students affected by the genocide in Gaza enforces a competition between MENA students and the rest of the student body when trying to access mental health resources.

“When I was trying to book appointments, I was competing with other students to get the earliest appointment,” said Alma. The effects of the genocide in Gaza have, in reality, been immediate and ubiquitous amongst the MENA and Muslim community in Montreal. The laborious process of “competing with other students to get the earliest appointment,” whilst juggling the increasing weight of a heavy school load, in addition to coping with the emotional turmoil of another day of genocide in Gaza, accumulates. Alma shared their experience with trying to "reach out," through the school’s peer support centre stating, "It becomes incredibly draining; you end up not wanting to see anyone."

Alma is also a Kurdish Syrian refugee (of a different genocide in the Middle East, although in which the West is still complicit). After undertaking the immense courage required to “reach out,” they were left mentally burnt out. “Sometimes I would look at the pictures [of the genocide] and think ‘Oh my god,’ cry, and think ‘I was in those kids’ shoes one day, not losing hope.’”

The daunting task of seeking help, only to be met with barriers and indifference, reveals a stark disparity in access to mental health resources.

The experiences of MENA students highlight a systemic failure to address our unique mental health needs, especially for those affected by the ongoing conflicts in the Levant, Yemen and the genocide in Gaza.

Every university student deserves fair access to mental health resources. But in moments of international distress, when the physical and mental well-being of one community is at much greater risk than the majority of the student body, universities must rethink this system of prioritisation.

To end our conversation on an aspirational note, I asked Alma how they would like to see targeted mental health support in action across campus. Although ambitious by university standards, Alma’s answer was refreshingly simple: hire more mental health professionals of colour. This strategy would not aim to fulfil a bureaucratic DEI (diversity, equity, and inclusion) quota, but to ensure that when a MENA student finally wins the resource competition, they won’t feel like they fought for nothing.

This article originally appeared in Volume 44, Issue 11, published March 5, 2024.

_600_375_s_c1.png)