Keeping languages and histories alive

How researchers transform Indigenous language documentation into learning materials

In 2019, Canada passed the Indigenous Languages Act, responding to a Call to Action from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

The Act allocated $330 million to support projects for reclaiming and revitalizing Indigenous languages.

Dr. Sigwan Thivierge, a Linguistics and First Peoples Studies professor at Concordia, believes that linguistics training has an important role to play in Indigenous language revitalization.

“I want to bring more Indigenous people into the field and also make the knowledge that we already have accessible to community members,” Thivierge said, “It’s about bringing the

community to linguistics, and bringing linguistics into the community.”

Thivierge herself is from Long Point First Nation in Quebec, an Anishinabeg community, as well as a speaker and learner of Anicinabemowin.

Quebec is home to nine Indigenous languages, spoken by roughly 50,000 people—the greatest share of Indigenous language speakers out of any Canadian province or territory.

According to Statistics Canada, between 2016 and 2023, the number of First Nations language speakers fell by almost five per cent.

Article 13 of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples states that “Indigenous peoples have the right to revitalize, use, develop and transmit to future generations their languages.” The UN estimates say that an Indigenous language dies every two weeks.

In response, UNESCO launched the International Decade of Indigenous Languages last year. Linguists like Thivierge say that Indigenous perspectives are crucial to reclamation and revitalization efforts.

There is evidence of some language revitalization among First Nations youth in Quebec. Statistics Canada revealed that in 2021, almost 40 per cent of First Nations children

could speak an Indigenous language, a figure nearly three times higher than First Nations adults aged 65 and older.

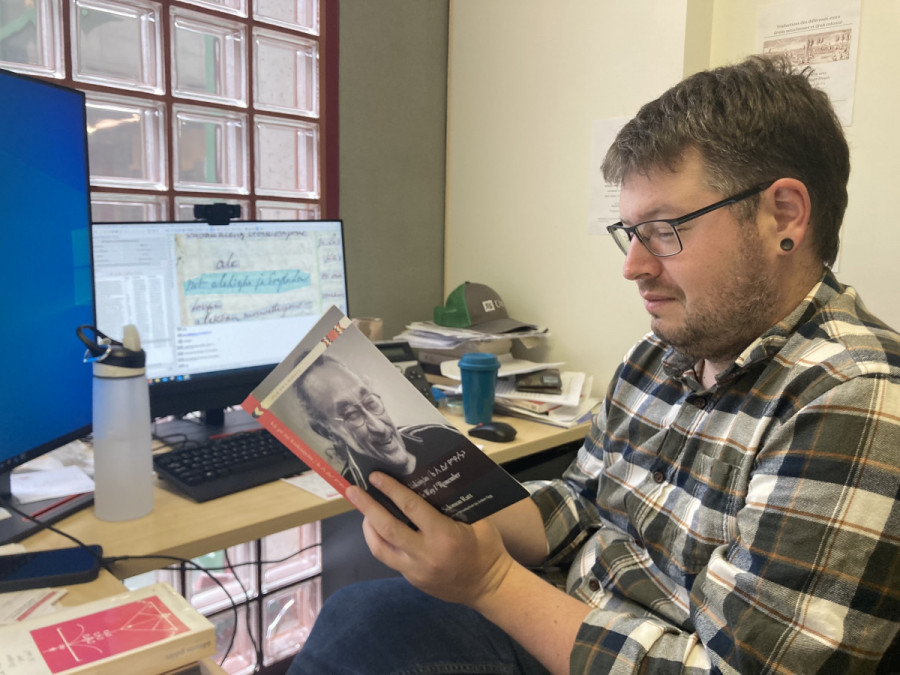

René Lemieux is a researcher at Concordia, who works on the Awikhiganisaskak Project to create learning materials for Abenaki using 17th century dictionaries written by hand on parchment. “Often, we’re working with information given to us by missionaries, so we have to be conscious of the layers of ideology,” said Lemieux, explaining that the goal is to process the existing documentation and return it to Indigenous communities.

“Linguistics is a field that lends itself to extractive research methodologies,” Thivierge said. Historically, settler linguists and anthropologists would collect data about Indigenous languages and then compile it into academic tomes which were inaccessible to laypeople.

“Communities want documentation, they want databases, they want their stories to be kept alive,” said Thivierge. “Yet, the data that does exist is not formatted for learners. You open a random page and see nominalising, or verb particles, and ask ‘What is this?’”

Learning Indigenous languages as living languages rather than only learning about them is crucial for the work of the Awikhiganisaskak Project, according to Raphael Bosco, a researcher for the project.

Reflecting on his experience as an Abenaki learner, he encouraged other settlers to take classes in Indigenous languages. “It helps with reconciliation of non-Indigenous people and Indigenous people,” he said. “Learning a language is always a way to see things from a different perspective.”

This article originally appeared in Volume 44, Issue 5, published October 31, 2023.