I thought I’d make my parents proud by attending university

How falling out of touch with my major made me feel like I was crushing my parents’ academic hopes

“I don’t know what to say when people ask me what you’re studying,” said my close friend to me one time. I chuckled and left it at that.

When my mom said it though, it felt like the world had gotten 20 times heavier, my frail second generation immigrant shoulders sagging at the weight of my ancestors’ expectations.

I started at Concordia back in fall 2020 as an honours student in linguistics, and I was thrilled.

After failing to get into the English and creative writing program—which I learned while waiting in line to hop on a plane back to Canada from Colombia in March 2020—it felt like the second coming of Christ to me. A light to follow. Although a very different field, I was given another chance to study something relevant, ambitious, and aligned with my love for the written word.

I felt smart and empowered, relishing in the performative act of being academically successful. After all, I had made it into an honours program, which was important to me because it made me feel like I was worth something. It felt good to think I wasn’t wasting my parents’ money on unsubstantial studies.

I convinced myself that studying the origins of language, discovering the secrets of why we speak a certain way, and of how dialects can evolve through time would bring me purpose. But I was simply settling for what was already accessible, seeing how it was the only thing I could do to not disappoint my parents.

Here’s the thing, though.

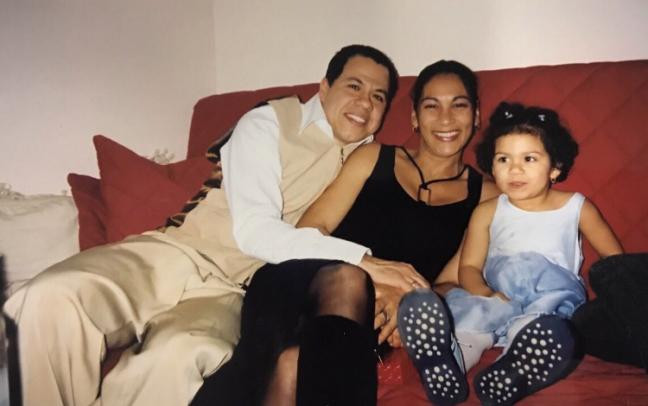

I was born in Montreal, and as a child of immigrant parents, especially of Hispanic heritage, mis papás never pushed me to accomplish anything, but would say they were proud of me nonetheless.

I took up swimming but failed my junior four–funnily enough–four times. So I quit. I played the violin for six years, the clarinette for two, and the saxophone for one. I was never really good at any of those instruments, but underneath all the nagging it took for me to practice, I knew my mom was happy I got the opportunity to at least try.

My mom grew up in a tiny Colombian village called Fundación. She lived in the humblest little house you could imagine, alongside her 12 siblings and her parents.

Over the years, she’d tell me stories of how she grew up. She’d tell me how, if it hadn’t been for the financial support she received from mi tío Ovidio, my mom would never have made it to high school. Without the help of two of her older sisters, she wouldn’t have gone to college either.

Education isn’t everything, but what it represents in terms of success is everything. It means you made it. It means you will make it.

Growing up, the fact that I had a roof over my head, enough food on the table, and was blissfully lost in my teenage entitlement was enough of a success to my mom. So was the fact that I was going to university after CEGEP. My parents were so proud. They gave me the opportunity to build my own expectations of what I wanted my life to be, but the one thing they were adamant about was that I do so by going to school.

It didn’t matter to me what I was studying because I just wanted to make them happy. But after a year and a half of struggling with my half-heartedly picked major, I finally called it quits. I felt like such a disappointment. My parents–my mom especially–had overcome so many cultural barriers to be able to come to Canada and offer her unborn child better life opportunities. By not being able to even dedicate myself to my studies and finish them, I saw it as a complete failure to what seemed like such a simple goal in comparison to what she had to go through.

I was ashamed of my uncertainty. I didn’t know how to deal with it, and I still don’t. It’s not like every child of immigrants is born with a how-to guide on how to deal with generational trauma and how it manifests, but it sure would be useful.

A couple of weeks ago, I finally mustered the courage to tell my mom I had dropped out of linguistics, by which I meant I had dropped my two program-related courses.

Through my computer screen, the pixelated image I saw of her showed me she wasn’t mad, just kind of sad. It broke me.

I felt guilty and anxious, fearing I was letting her down even though she wasn’t showing it. By being indecisive about my future, I was undoing the work her and my dad had done to ensure I would lead a good life—a better life even—and that was wrong.

I often feel uncomfortable in my privilege, and want to strip it away like a wrongfully awarded medal, but not acknowledging that I was given this life intentionally and purposely would be disrespectful to my parents.

I’m tired of feeling like I’m letting their undeserved pride slip away from my fingers, like the fine sand you find en las playas de la costa, where they’re from. I’m tired of being defined by my generational trauma.

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)