How Mental Health Is (or Isn’t) Handled in Asian Communities

An Intergenerational Gap Separating Parents From Their Children

Growing up with two Asian parents who immigrated to Montreal in their thirties, Christy Lo says she grew up very Chinese.

Her dad is from Hong Kong and her mom from Cambodia. Lo attended Chinese school on Saturdays and spoke Cantonese at home with her dad. She admits her Cantonese skills have gotten rusty over time.

Certain pressures are synonymous with an Asian childhood. Succeeding in school and doing so with a stiff upper lip are two pillars of a first-generation Asian kid’s upbringing for many.

Lo, now a psychology student at Concordia, can attest to that; these pressures took a toll on her mental health as well.

“My family doesn’t believe in mental health,” she said. “It’s not a thing for them.”

When she would tell them how stressed or depressed she was feeling, they would tell her, “You’re just sad for a little bit, why won’t you just get over it? If you’re stressed, why won’t you stop being stressed?”

This attitude hit its peak at the end of high school, when Lo was in grades 10 and 11. Because of Bill 101, she had to attend French school. For her and her peers, learning French from scratch was a huge obstacle. She could follow the material but struggled to understand it in French.

At the time, there was a huge disconnect between her and her family. She wouldn’t speak to anyone at home. Her parents would get upset at her for not speaking to them, but she kept quiet because they would only yell at her when she expressed her emotions.

She started to get depressed. Her parents would question her bad grades, searching for a familiar problem they knew how to fix. When she would routinely explain the language barrier and the difficulties she was experiencing, her parents would simply tell her, “Just learn the language.”

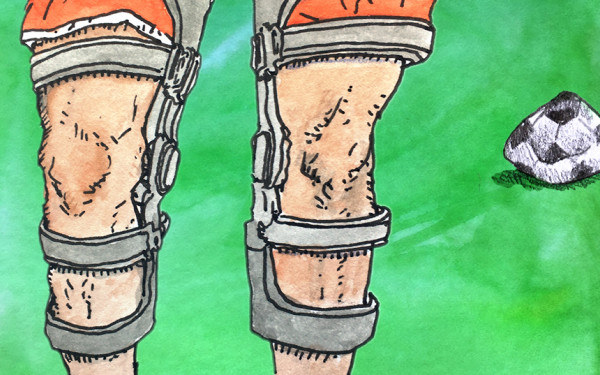

“I didn’t understand my feelings because [depression] doesn’t exist, but I’m feeling this,” she said. “I started cutting myself and being on the more suicidal side. Things didn’t fit. And when things didn’t fit, there was no way to cope with it.”

When she started cutting herself, she would wear long-sleeve shirts to cover her wrists. Her parents didn’t find out because, as Lo put it, they weren’t looking for anything.

Like many Asian households, she grew up with a “doors always open” policy. Lo rebelled and kept her door closed, further distancing herself from the rest of the family. “I fought for the right to close my door! My [younger] brother can close his door now because [of me],” she said through scattered laughter.

When she first told them she was cutting herself, they were very hurt and cried. The next day, her parents were less empathetic. They told her, “Why would you do that? You’re just leaving scars on your body, and that’s gross.”

As things kept escalating, her parents were forced to accept her depression when she tried to take her own life. While her parents didn’t fully understand Lo’s depression, they finally acknowledged this was weighing heavily on their daughter.

“It’s not like I’ve forgotten what they’ve said. They’ve said some pretty hurtful things,” she admitted. “At least it’s in the past. They’re much more understanding now, and they’re apologizing for what they’ve said.”

Once Lo was in CÉGEP, her parents made more efforts to support her. Even so, it wasn’t without bumps in the road.

“There were times where they would get frustrated, because to them it’s just feelings,” she said. To Lo, her parents seemed to feel it was nonsense.

Her parents started to change their attitude only a year ago, she said. “They give me my own space and have put less pressure on me.”

She grew up similarly to many Asian kids, with her parents pressuring her to pursue medicine or law. Now, she understands their berating came from a good place. Her parents grew up in poverty and wanted what they felt was best for her.

Since her roughest patch in high school, things have become more stable. “[My parents] understand what it means to see a psychologist. Even though they can’t help me, they understand there are other people who can,” she said. “Not everything is in their power.”

Ahlyssa-Eve Dulay, an illustration student at Dawson College, felt the same struggles as Lo in high school. The high expectations and strict rules her parents grew up with in the Philippines were put on her and her older brother, with Dulay taking the brunt of it.

Dulay grew up in Côte-des-Neiges, going to French schools attended by mostly Filipino kids. Usually, their first language was either English or Tagalog, so learning French didn’t come naturally.

Pursuing a career in the arts isn’t always welcomed in Asian households. A career in medicine or business provides a stability prized by Asian parents that is not found in the arts. Dulay acknowledged how fortunate she is to have more accepting parents, keeping in mind several of her own friends forced into nursing by their Filipino parents.

“My mom is supportive of me being an artist,” she said. “I’m very lucky to have family members that let me have a choice.”

“My family doesn’t believe in mental health. It’s not a thing for them.” —Christy Lo

While her parents agree on her education, they don’t see eye to eye on everything. “Our problems here aren’t comparable to their struggles,” she said. Dulay remembers her parents scolding her. “You’re not suffering how we suffered there in the Philippines,” they would say. “How can you be depressed when we came here so you can have a better life than ours?”

Oftentimes, first-generation kids feel guilty for complaining about their lives in Canada because they’ve heard their parents’ hardships in their home country. Growing up in a developing country like the Philippines is never comparable to growing up in the Western world, and Asian parents will make that difference known.

There was an innate dismissal of Dulay’s emotions, with her parents saying, “I suffered more than you. Why are you sad?”

For Dulay, talking about your emotions to your parents is like showing a sign of weakness.

“My mom told me, ‘If you need someone to talk to, you can talk to me,’ but I know I can’t talk to her.” Opening up that conversation would only lead to more judgement and misunderstanding.

The language barrier was its strongest when she was in high school. “[My parents] don’t know French, and it’s hard to teach your kids how to do their homework when you don’t understand French,” she said. “They got frustrated, and it showed.”

She remembers her mother routinely getting upset over her assignments. Dulay understands now her mother wasn’t upset at her; she was upset at her own inability to understand the homework.

The ongoing pressure to succeed and the struggle of everything being in French were the cruxes of her turbulent emotions.

“I was sad almost every day. It was the first time I felt [depressed],” she said. “You have all these expectations and pressure on you.” Her fear of failure was hard to shake.

After telling her parents how she was feeling, her words were met with a rocky reception. “My mom didn’t know how to react, so she just got angry. My dad tries to be more empathetic, but he’s still confused.”

“A lot of Filipinos love to judge and compare their kids, and that took a toll on me,” she said. “It stays with you.”

The majority of her education revolved around being better than her peers to finally receive praise from her parents, but even when she did her best they wouldn’t praise her. They would always push for more.

“I’m doing this for you,” she remembers thinking. “You forget you’re doing this for yourself.”

Amanda Wan grew up with more academic freedom than stereotypes would allow. “Grades were important but not the focus,” she said. Wan’s dad is Chinese, Filipino, and Spanish, while her mom is Italian and French.

Wan, a communication studies student at Concordia, remembers her Filipino grandmother always asking, “Why don’t you want to be a nurse like me?”

Even so, her decision to pursue something outside of the medical field was well received, a reaction she’s grateful for.

Growing up attending a predominantly white school, Wan was bullied for being Asian. They would laugh at her, call her names, and exclude her from things. This led to the beginning of her anxiety and depression.

At such a young age she didn’t know exactly what she was feeling, but she did know it wasn’t normal. Something was wrong but she couldn’t pinpoint it. “It was a weird place,” she said.

Just like Lo and Dulay, things were at their worst when Wan was in high school.

She was struggling with school and her sexuality. Her social anxiety grew stronger and it was hard for her to make friends. She started to self-harm. A classmate of hers found out and told the school, leading to a very heavy conversation over the phone between the administration and her parents.

“My parents were shocked and confused, and started off by thinking how I could feel this way if my life is ‘perfect,’” she said. “They then came around and got me some help.”

“My parents were sad to hear I was struggling and wished I told them sooner,” she added.

Wan was clinically diagnosed with depression and anxiety towards the end of high school, and was diagnosed with Attention Deficit Disorder when she was in CÉGEP.

Mental health is something she’s struggled with for most of her life, and she admits it’s been a struggle. While she’s had her ups and downs, she says she’s getting better.

“I was never really able to open up to my family about the struggles I’ve faced. It took me years to finally open up,” she said.

“They never really took it seriously at first, and I was just scared to let them down,” Wan said. The fear of letting their parents down is something at the front of many first-generation kids’ minds.

Slowly, a bridge is being built between Asians born in the diaspora and their immigrant parents. While the intergenerational gap is still vast, those struggling with their mental health are building up the strength to tell their parents and start the conversation.

“I was always supposed to see how I’m privileged, but that never really has anything to do with mental health in my opinion,” said Wan.

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)