‘Haiti Betrayed’ Reveals Reality Behind Canada’s Reputation as Peacekeeper

Cinema Politica Film Exposes How Canadian Foreign Policies Have Crippled the World’s First Black Republic

In one of the opening scenes of Haiti Betrayed, a Haitian man stands alone outside of the Canadian embassy in the arid landscape of Port-au-Prince, yelling out in frustration.

His cries are clearly directed towards the Canadian government and its presence in Haiti.

With his back towards the camera, he screams: “We don’t have anything against Canada! Why are you against us? Why do you hate Haitians?”

This is a pinnacle moment, as the film spends its entire length tackling these questions.

Cinema Politica is a non-profit media organization, founded in 2003, that regularly screens political, alternative and radical films at Concordia. At the screening for the film Haiti Betrayed, one of the researchers involved in the making of the film, Nik Barry-Shaw, mentioned it was created within an nine-year process.

That broad time-period is unsurprising, as the film effortlessly weaves together various moments in 21st century Haitian history.

The film is calmly narrated, yet abrasive—and centres Canada’s responsibility over Haiti’s current political-state as something that has been historically ignored, but now cannot be turned away from.

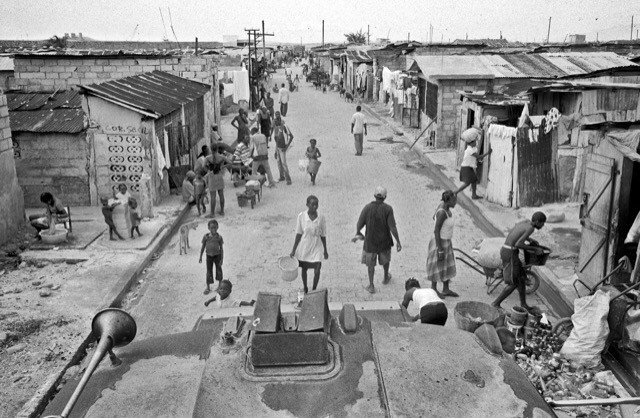

Director Elaine Brière said the film began accidentally. Whilst on a photography project in Haiti in 2009, she had been taking photos in Cham Mas, a major square in Port-au-Prince, when a poor man approached her. The man mistook her for a journalist, and told her she didn’t know what was really happening in Haiti. There had been UN soldiers patrolling the area, so she neared him so they could speak more discreetly.

“They are killing us!” he told her. “We are poor people. Tell them to stop.” And then he began to cry and walked away. Brière said this moment shook her to the core, and her film was consequently a response to this man’s plea.

As the film recounts, Haiti began as a slave colony and became the world’s first Black republic after the Black Haitian slave armies defeated Napoleon’s French army in 1804. Encountering freedom in a world that was still riddled with slavery, Haiti was shut out of the world’s economy.

As Brian Concannon, the executive director of the Institute for Justice and Democracy in Haiti, mentions in the film, if Haiti was allowed to succeed, it would have proven to the world that Black people were competent enough to run their own country.

Because the West feared slave revolts in their own nations, they attempted to discredit Haiti by either ignoring or exploiting it—France demanded Haiti pay it 150 million francs in exchange for its freedom, and America only acknowledged Haiti as a state 58 years after its independence.

Then, on top of still dealing with the extreme debt Haiti was paying to the French government, Haiti was obliterated by discriminatory foreign practices in the early 21st century.

This included the U.S. invasion of the country from 1915-1920, where U.S. marines gained control over Haiti’s national bank and customs operations. This also included the Haitian Massacre by the Dominican Republic in 1937—where the racist Dominican president, Rafael Trujillo, massacred up to 35,000 Haitian immigrants at the border because he saw them as racially and culturally inferior, and therefore an inhibitor to the growth of the Dominican economy.

After the massacre, Trujilio was ordered by the U.S. to pay Haiti reparations—but not all of it was paid, and, due to corruption by the Haitian government, not all of the funds paid reached the families of victims.

The documentary is conscious of this broader history of Haiti, whilst it specifically centres on Canada’s involvement in Haiti’s political state. The film is particularly concerned about how Canada helped to topple Haiti’s first democratically elected government.

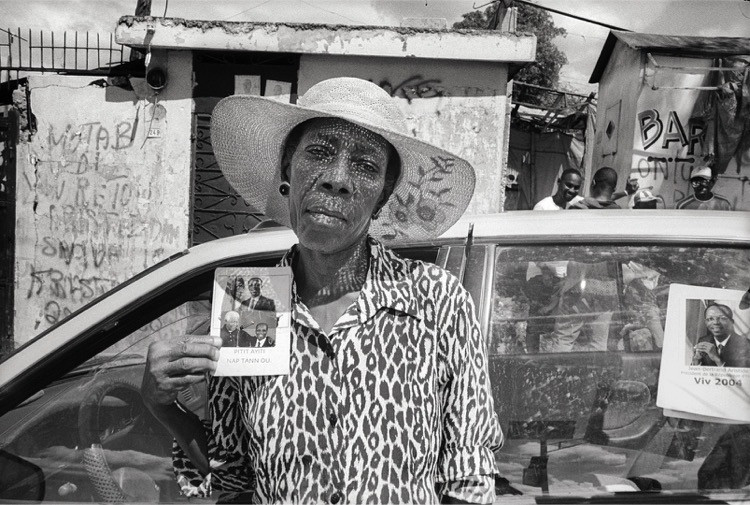

The elected administration was the political organization, “Lavalas” and it was headed by President Jean-Bertrand Aristide, who won the election in 1991. In the film, Patrick Elie, Haitian Secretary of State for Public Security from 1994 to 1995, with stars in his eyes, describes the Lavalas administration as one that wasn’t pursuing greater political power for its own interests, but as one that consistently pushed forward what the people of Haiti truly wanted.

Haiti at this time had an impoverished majority, and Aristide was mostly popular because he spent his career advocating for this group.

One of his main priorities was to redistribute the nation’s wealth in a more equitable way.

The Lavalas administration had numerous successes—Haitian literacy rate increased by 20 per cent, malnutrition dropped by 12 per cent and 138 new secondary schools were built in 14 years.

“It’s shameful that the treatment of Haiti is disguised as “helping Haiti.” — Elaine Brière.

During this time, there was an extreme power imbalance—this inequality was due to the country being mostly controlled by a small group of wealthy families, according to the film.

These families, backed by multinational corporations, opposed the Lavalas government and its dedication to forcing tax collections from the rich.

The disapproval eventually led to the forced removal of the Lavalas administration from office, twice—the first time with the help of the Haitian army in 1991, and then, again, with the help of the U.S., France, and Canada in 2004.

As well as France and the U.S., Canada had pernicious reasons for supporting the 2004 coup that led to the ousting of the Lavalas government, according to the film. (France had felt threatened by Aristide in 2003—after he gave a speech demanding that France pay Haiti reparations of 21 billion US dollars—the modern day equivalent of the 150 million francs that Haiti was forced to pay France after the end of slavery.) Canada has since used the coup as a way to further exploit Haiti.

An example of this exploitation is the Canadian company Gildan, whose workers in Haiti made less than a dollar a day whilst the company gained millions. The Aristide government attempted to double the minimum wage but this was not seen as popular to some of the rich elites. The exploitation of Haitian workers by Canadian multinational corporations therefore continued.

In the film, the revelations of Canadian complicity hit viewers like a brick, and whenever it’s done, it’s accompanied with an ominous audio back-track that rouses feelings of suspiciousness and unease. It’s similar to the music you’d hear in true crime dramas; it’s as if the film is sonically replicating the clandestine, stealthy nature of Canadian foreign policy.

Another repeated feature that permeates the film is its fearless attitude towards the presentation of violence. Images of brutal attacks against Hatians, lifeless mutilated bodies lying in the streets, burning vehicles; these are all casually shown without warning, in a bland, understated and emotionless manner. This seems strategic, as it mirrors the indifference foreign nationals express towards the suffering of Haiti—how ignorance has become more normalized than intervention.

Brière said she was selective about the violence she chose to include. It was imperative to include an accurate example of the brutality without being too gratuitous, she said.

Because the film focuses mainly on events around the Aristide administration, it doesn’t completely extend to Canada’s current complicity in Haiti’s political state. The Moïse administration came into power in 2016. The poor majority have largely protested his regime for its fuel hikes, corruption, high rates of unemployment, spiking inflation, currency devaluation, and extrajudicial killings by government officials.

Ottawa, however, supports the government and its repressive police force. Canadian officials have blamed any violence on protesters, and have told them to resort to ballot-boxes and voting instead of protesting. This is ironic, as Canadian officials took part in election interference when they raised funds in order to exclude the Lavalas party from running in the 2010 Haitian elections.

The Moïse administration itself was brought into power through voter suppression. One in five eligible voters voted—he therefore only received 600,000 votes in a country made up of 10 million citizens. After protests arose due to his election, Canada released a statement defending him.

Canada has repeatedly ignored the violence of the Moïse administration. Perhaps the most egregious example of this violence is in November 2018, when the U.N. confirmed involvement by the Haitian government in a massacre that left up to 71 people dead in Saline, a neighborhood of Port-au-Prince.

According to an article in Ricochet, Canadian police have also provided support and training to the violent forces that have maintained Moïse’s rule, and have remained silent on it.

When asked if the film resonates with the current turbulence around the Black Lives Matter movement, Brière agrees there is a relation, as “Canada has become a full-fledged member of the club that keeps the boot on Haiti’s neck and doesn’t let them breathe.” She acknowledges how the histories of Haiti and Black Lives Matter are both rooted in colonialism, and how Haiti’s suffering is rooted in its existence as the world’s first Black republic.

“It’s shameful that the treatment of Haiti is disguised as “helping Haiti,” said Brière.

“I wonder when we are going to let go of punishing Haiti every time they try to bring a modicum of social justice to their long-suffering people.”

At the end of the film, we’re circled back to the man yelling outside the Canadian embassy, in the dusty, open terrain of Port-au-Prince.

“We are tired,” he chants. “The Haitians aren’t against you! Why are you against the Haitians? Why do you support the forces against the people?” he asks.

The film ends there—leaving the audience, together with the man, begging for an answer.

*The film Haiti Betrayed is available for rent through Cinema Politica On Demand. It can be accessed here.

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpeg)