Get out of the way white fragility, let’s eat!

TikTok tries a staple in African cooking; Fufu

Fufu, a West African dish, has become foodie TikTok’s latest obsession.

The TikTok trend has many white people trying and enjoying Fufu, a popular traditional Akan dish among many African cuisines most notably Ghanaian, Nigerian and Togolese cooking. The trend, which emerged in early February, highlights an issue that is pertinent to talk about, but is often avoided; how narratives of Africa have historically been shaped by white supremacy.

The trend started as an exploration into a culture whose food had never really been looked at by the rest of the world. By the end the trend had transformed into something more, an honest reevaluation of our Western understanding of good food.

Decades of Black youths have been forcibly assimilated into western white society in many ways, including the food they eat when around white people. I saw this happening in my elementary school and even my high school. In the school cafeteria, the line to the microwave was usually full with pastas and soups, dishes without much spices or vibrant smells. Anyone who chose to warm a lunch made with flavors beyond salt, pepper and oregano faced the scrunched up noses and insults of the kids who smelt it. I still remember hearing teachers telling us that we were permitted to eat in class so long as it didn’t have an odour.

Amongst other things, this hatred for non-white traditional cooking is the result of narratives of white supremacy. Black people are taught that their traditions are lesser than, simply because white people are uncomfortable with being inadequate. Admitting that centuries of oppression and racism towards the Black community would mean admitting that white people were wrong. It would mean addressing the imbalance of power, allowing space for Black politicians and leaders, and it would mean reevaluating every single institution around the globe.

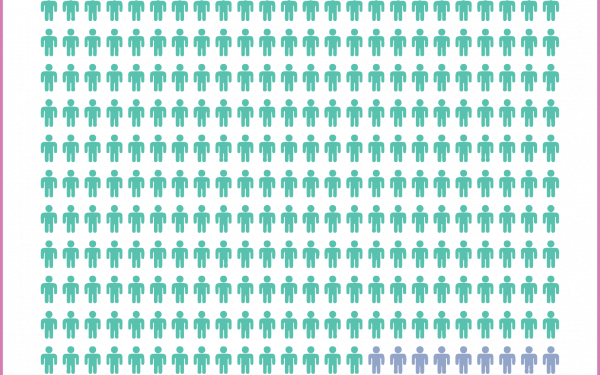

When it comes to cooking, white food has never been objectively better but because of white supremacy, it has dominated the culinary world for decades and has been deemed more refined. Roughly 70 percent of the world’s best restaurants are from traditionally white countries, which isn’t surprising. It is why you’ll pay more for a steak and mashed potatoes at a steakhouse than dim sum from a Chinese restaurant. It is for the same reason that white people get upset when you ask what spices they use. Addressing people’s standards of cooking, or even being, as different from the white standard makes white people fearful.

The economic, strategic, and even cultural warfare that the western world has waged against Africa has certainly helped in debilitating a continent that has so much. White people have managed to distort the narrative so harshly that western countries genuinely believe they’re helping. What would Bethany, Ashleigh and Tiffany do if their mission trips to Africa were cancelled? Who would Gordon Ramsay be if African cuisine had had the global stage that English food holds. Would African countries hold more sway globally than the United States?

White people do not want to have an authentic understanding of Africa. It is easier for them to imagine the continent as a place that needs us rather than a place that thrives in spite of us.

People from ‘first world countries’ think of Africa as poor, desolate, and underdeveloped because of systems of white supremacy. In education, for instance, white narratives of history around colonization creates a sense of inferiority in Africa that festers into our current understanding of the continent.

White people do not want to have an authentic understanding of Africa. It is easier for them to imagine the continent as a place that needs us rather than a place that thrives in spite of us.

This miseducation is perpetuated by western culture and media. You might remember the advertisements for “feed the children” that exclusively showed African children—usually living in huts. Perhaps you might think of the news showing footage of a hospital filled during the Ebola outbreak or even the battle footage in Somalia. Do you think of the pyramids when you think of African success? Have you ever thought about why hundreds of conspiracy theories surround the pyramids? Did you think it might simply be because of white supremacy that our time perceptions are centered around Europe and not Africa, where humans first originated? We are rarely shown an image of the continent as a place rife with culture and innovation.

While the TikTok videos may just be a trend, bound to die down eventually, it is also a lesson in culture. The videos are a symbol of progression. But it is just that—a symbol. It comes from a generation who laughed at jokes about poverty in Africa. It comes from a generation that yells the N-word while playing video games--because it’s ‘just a curse word’. It comes from a generation that, while ‘addressing’ racism and white supremacy through black squares and preformative activism, forgets to look back at the damage and the pain they inflicted through inconsiderate things they have done.

In 2020, we were finally starting to see some white people acknowledge white supremacy and privilege.

In 2021, we are starting to see a global reeducation in culture through trends just like the one about Fufu. It is a move towards addressing the misconceptions and the misinformation surrounding Africa in the western world.

However, a year has passed since the riot in the USA began and we are hardly closer to deconstructing white supremacy in public institutions. We can continue to reeducate ourselves, but we cannot move forward if the same systems that made us overlook white supremacy are still in place.

It’s great that some white people can say, “I’m educating myself so that I can be a better ally,” but the issues run deeper than individuals. Until the collective agrees that changes must be made, progress will remain stagnant and satisfied by symbols.