Frame to Frame

The Power of Non-Violent Palestine

Budrus tells the story of a village’s struggle to keep its land amidst Israeli fences being constructed between the West Bank and Israel in 2004.

Seven villages were slated to have their land taken away by a new separation wall, including the town of Budrus, where the barricade would cut through their cemetery and block access to over 3,000 olive trees—the lifeblood of the villagers.

Filmmaker Julia Bacha takes us through the non-violent actions of the people of Budrus, from the movement’s infancy to the Israeli decision to move the planned wall to match the “green line,” the border after the six-day war of 1967. Cinema Politica will be screening the film on Friday as part of Israeli Apartheid Week.

The documentary begins with villager Ayed Morrar speaking to the camera, setting the tone for the film. “We don’t have time for wars, we want to raise our kids with hope,” he says. “It is in the interest of the Palestinian people to take the path of non-violence.”

{image_1}He champions a peaceful approach to resist the Israeli encroachment. One of the members, who helped found an arm of the Fatah party, was arrested when he was 19 and spent six years in prison. The film follows his struggle to unite Palestinians of differing polity and Israeli activists to join the march against division of his village.Bacha’s documentary gives an intimate picture of Budrus, a small village with a population of 1,500. On the second day of the protest Israeli soldiers have arrived early and uprooted 80 olive trees. The pain on villagers’ faces gives away just how essential they are, these trees that they’ve given their mothers’ names.

After that day, Morrar encourages his daughter, Iltezam, to bring women to the protests. Their decision to march on the front lines makes the army’s choice to use force on peaceful protesters all the more difficult.

It becomes a race, with protesters running towards bulldozers with soldiers alongside them. Things escalate. The soldiers begin beating the women and shooting rubber bullets. Reaching the bulldozers, just after soldiers have encircled them, Iltezam finds herself on the wrong side of the line, and jumps into the hole made by a bulldozer. And all of a sudden, the other women jump in too.

{image_2}“They had no other option to take the bulldozer and go away,” she says in interview after the incident.As the protest grows, the number of Fatah, Hamas and Israeli activists coming to support Ayed are shocking. It’s the first time many of the villagers have seen non-soldier Israelis, and the ensuing cooperation is nothing short of inspiring.

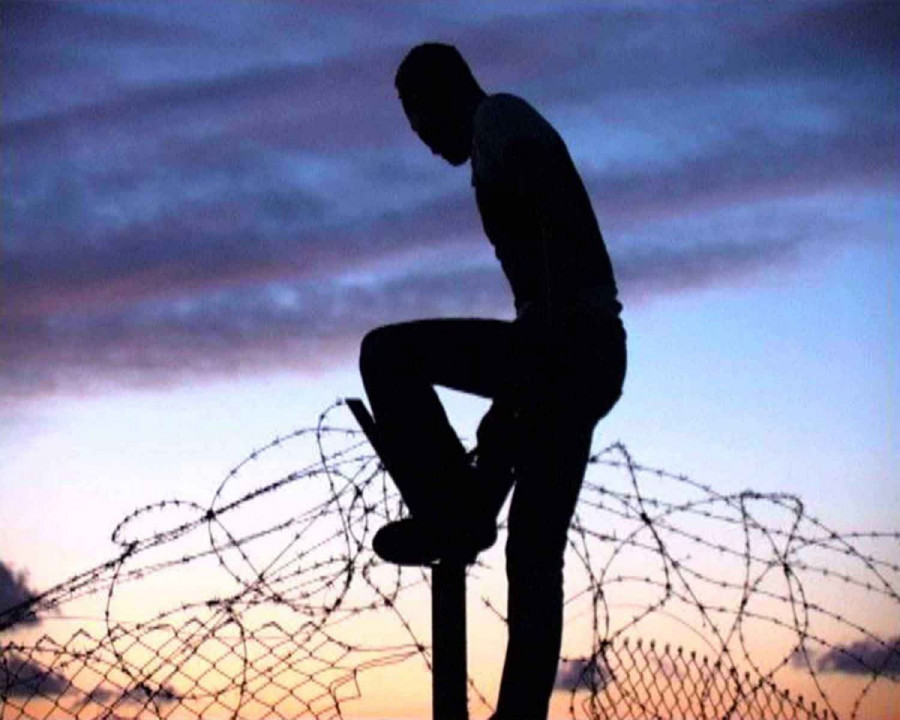

The film climaxes with soldiers occupying the village, and a night where villagers cut through Israeli barbed wire. Throughout the documentary, there are clips of Israeli media coverage from Channel 1, where at one point the Deputy Defence Minister recommends putting Israeli protesters on trial.

As Budrus comes to a close, we learn that the village was able to keep 95 per cent of their trees at the end of the struggle. Because of their non-violent approach, the villagers earned international support. And while the army spokesperson interviewed claims it had nothing to do with the protests, the Budrus method has been repeated across the West Bank since.

Budrus / Cinema Politica / J.A. de Sève Cinema (J.W. McConnell Building, 1400 de Maisonneuve Blvd. W.) / March 9 / 7:00 p.m.

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpeg)