Does Concordia Have a Military Complex?

Questionable Links Between ConU, Military Uncovered

Last week, The Link received an email—subject “Concordia’s Military Complex”—containing information about the university’s ostensible ties to the Department of National Defence and military industries.

The email was sent by a student activist from the newly formed Anti-War Efforts Group.

“It’s an attempt to show that the military is deeply involved in Concordia’s administration, deeply involved in the funding of Concordia and deeply involved in the research at Concordia,” said Gabriel Velasco, one of the original members of the AWEG.

The group sprang up in September as an offshoot of the Mob Squad, a campus-based activist organization that supported the student strike and stands against the privatization of universities.

So far, the Anti-War group has roughly a dozen active members and a mailing list of about two hundred people.

The group’s research was partly based on a five-year-old pamphlet entitled “Military Research in Our Universities” by another local activist group and summarized in a flowchart scribbled on the back of a concert poster—hardly what one would call compelling evidence.

Indeed, it would have been easy to disregard their allegations, had they not found a few real—albeit ambiguous—links between Concordia, the defence department and large corporations involved in different aspects of military production.

While Concordia’s so-called military ties aren’t nearly as clear-cut as they appear in the AWEG’s makeshift flow chart, they do appear to exist.

In reality, the picture is blurry: a web of hazy associations encompassing a research council, several major corporations and the university’s highest administrative body, the Board of Governors.

“Embedded in the University”

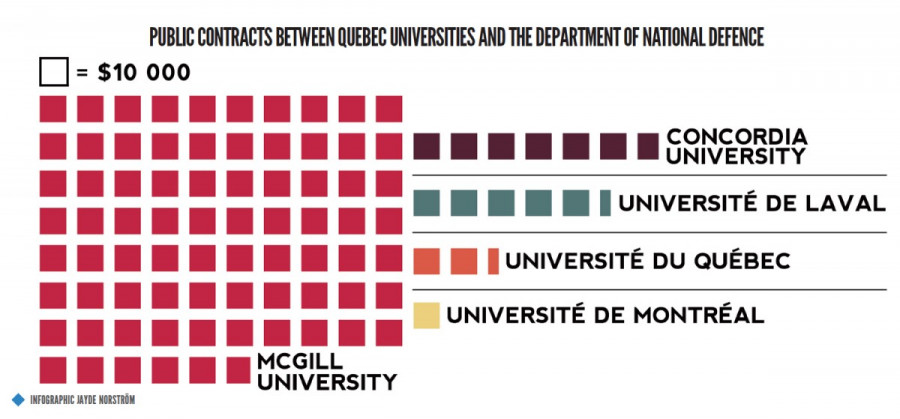

Since January 2011, the Department of National Defence has awarded nearly a million dollars in research funds to Quebec universities, according to openly accessible information from Public Works and Government Services Canada.

While McGill University has been the recipient of the lion’s share of this sum—$759,374—Concordia received the second-highest amount of any of the provinces’ universities over this period, with $68,956.

In an email to The Link, a university spokesperson explained that two of Concordia’s most recent contracts with the defence department were for scientific literature reviews.

Although they don’t call themselves pacifists, members of the AWEG oppose war under almost all circumstances and say that military research has no place in universities.

“It would be difficult to argue that the money spent on military research couldn’t be better spent on something else,” said Terry Wilkings, another member of the group. On Nov. 29, the AWEG plans to march in a protest starting at Phillips Square against Canadian sanctions on Iran.

According to Velasco, Concordia’s contracts with the defence department are merely the tip of the iceberg.

“There are other governmental agencies that deal with military stuff,” he said. “If you look at those contracts, we get even more money.”

Equally troublesome to Velasco are Concordia’s links to defence companies at different levels of the university’s administration.

“The military is embedded in the university,” he said.

Velasco pointed to Michael Novak, who sits on the school’s Board of Governors and is also chairman of Canadian engineering giant SNC-Lavalin.

Until it sold its bullet-making division to General Dynamics in 2006, SNC-Lavalin was one of the largest producers of ammunition for the Canadian military, and was a supplier to the American and British governments.

Earlier this year, SNC-Lavalin was at the centre of a scandal involving a Senior Executive of the company’s subdivision based in Tripoli, which was building a prison in Libya and had close ties with the later-deposed dictator, Moammar Gadhafi.

Velasco also voiced concerns about a few members of the school’s Industrial Advisory Council.

Made up of over 30 members that also hold important positions at major companies, the council helps direct program development at Concordia and acts as an intermediary between the university and industry leaders.

Velasco claimed that several members of the council are also executives at what he dramatically described as “straight-up military corporations.” The list includes Presagis, Rolls-Royce Canada, Pratt & Whitney Canada and MDA Corporation.

None of these companies are out-and-out military corporations, but all are involved in military production and are publicly listed as defence companies.

“I think it’s important that as students we start questioning who’s sitting on our administration and what sort of control corporations have at our university,” Velasco said.

“It’s an attempt to show that the military is deeply involved in Concordia’s administration, deeply involved in the funding of Concordia and deeply involved in the research at Concordia.”

—Gabriel Velasco, Original Members of the AWEG

Fire-Fighting Drones

Of particular concern, Velasco argued, are Concordia researchers’ ties to the development of military unmanned aerial vehicles, commonly known as “drones.”

“The research that’s done at Concordia, specifically regarding UAVs, is being used in various missions and operations in conflicts around the world right now,” he said.

In one corner of his elaborate handcrafted flow chart, Velasco pointed to a professor’s name: Dr. Youmin Zhang—with arrows winding upwards connecting it to various companies all the way up to the Israeli military.

In an interview at his office, Zhang was puzzled to hear that he had been implicated in the design of military drones.

“It’s really a surprise to me,” he said with a bemused look. “We didn’t touch on that, we didn’t work on the military applications.”

He said the goal of his research is to help create a navigation system for UAVs that would eventually replace manned aircraft on dangerous assignments, such as tracking forest fires and carrying out search-and-rescue missions.

“My original motivation—my dream–is to try to improve the safety and reliability of civilian applications. We try to save lives; save airplanes.”

Zhang said he has never received any funding from the Department of National Defence, nor has he ever been approached to work on military technology.

“I love peace and I think war between countries is bad,” he said, sitting behind his desk, decorated with small-scale model passenger planes and military jets.

Iman Sadeghzadeh, a PhD student and teaching assistant to Zhang, said the anti-war activists’ concern is typical of the widespread misconceptions clouding the public’s view of UAV technology.

“When I tell my friends I’m working on UAVs, the first thing they say is, ‘Is it for a military application? Are you making drones to send to Afghanistan or Iraq?’ And my answer is, ‘For sure not.’

“We are working on fault-tolerant systems to saves lives, not to take people’s lives.”

Although his research is intended for civilian use, Zhang said his work is publicly accessible and could potentially be used by the military—and anybody else for that matter.

“You know, [scientific research], it’s a kind of knife,” he explained. “You can use it for surgery or you can use it to kill someone.”

Like Zhang, Sadeghzadeh is strongly averse to working on attack drones.

“I myself would never like to work on military applications. Never.”

_864_575_90.jpg)

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

_1_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)