Dear Fellow Immigrant, Your CV and Degree Are Not Valid Here

If You’re Coming to Canada, Prepare to Hit the Reset Button on Your Achievements

I remember sitting in my family kitchen in Dubai, door closed, notebook ready. It was 2020 and I was waiting. That day, I was to receive a call that would end up lasting for two hours.

The call was for a so-called cultural orientation—a mandatory session meant to prepare me for my immigration to Canada as a Syrian refugee. Typically, this orientation would be run in-person over the course of a few days, but COVID-19 had reduced it to a two-hour crash course via phone call.

“This should be easy,” I remember thinking. A cultural orientation? As if I haven’t already been educated on North American culture my entire two decades of life by TV, film and countless hours on Reddit and Instagram. This cultural orientation would be a formality rather than an actual learning experience, I assured myself.

The call eventually came and a man from the International Organisation for Migration headquarters in Egypt spoke on the other end. In that call, we covered post-arrival in Canada, housing, how Canadian healthcare works, culture and amongst other things. I was proud of my youth and my know-how. None of the information really shocked me.

That was until the very end, when we reached the topics of education and employment in Canada. It was time to discuss possible employment barriers for immigrants. The IOM representative explained there were three barriers: language, education and experience.

A single sentence from the man stuck out to me, and it is something I repeat to anyone who wants to migrate here from the Middle East: “In Canada, they only care about Canadian work experience and Canadian education.” I found this to be the most revealing and most useful tip, like I was being let in on some giant secret—how lucky I was.

The man on the call explained that immigrants arriving in Canada often require a severe ego check. He said, a little facetiously, that people arrive expecting to be bestowed with the same job, the same title and the same prestige they enjoyed back home. This is a sore mistake, he told me. And you know what? He was absolutely right.

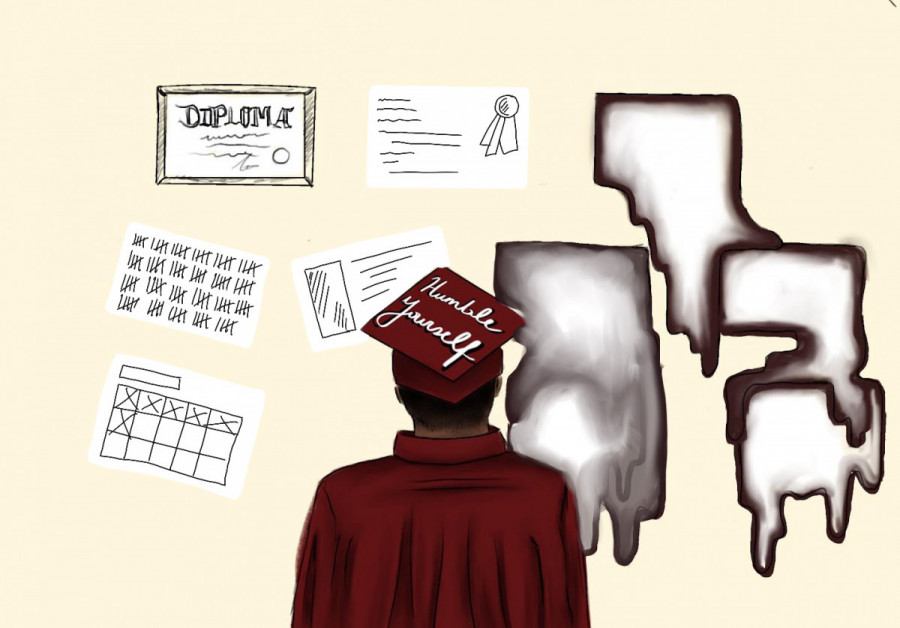

As a refugee or immigrant, the expectation to continue from where you left off is viewed as naive, even deadly. How dare you expect that your decade-long career would hold even an ounce of worth in Canada? How dare you expect that your expensive, accredited university degree would hold any water in Canada? Please, sit down and humble yourself, habibi.

Let me draw a map of the paths and ultimatums we’re faced with. From what I’ve experienced and observed amongst the Syrian diaspora, there are four possible scenarios available once you land in the country. In the first, ideal scenario, you arrive young enough to complete your secondary or higher education in Canada, and your Canadian degree secures your foot in the door..

In the second scenario, you arrive with a foreign degree and job experience already in hand. If these don’t originate from Europe or elsewhere in North America, they may as well appear on your CV as incoherent gibberish to Canadian employers. And so, you bravely decide to repeat your education or restart your career; a giant setback if you’re older and financially responsible for a family.

In the third scenario, time is a luxury and money is scarce. You begrudgingly decide to work minimum-wage or entry-level jobs to support your family. On paper and in your heart, you know you’re overqualified for these jobs.

The fourth scenario, one common amongst fathers, is to leave your family in Canada and return to your country of origin, assuming it’s safe enough, to continue in your preferred occupation. You retain your level of employment and your salary, which you then send to your family abroad.

The financial and emotional strain that this brings to individuals and families—particularly immigrant men and fathers who come from cultures that expect men to provide—is immeasurable. These men are robbed of their dignity, their achievements, their self-worth, their families—and sometimes, they’re robbed of their life. I’ve heard stories of immigrant men—one of them being the father of a close friend of mine—who suffered from such deteriorating physical and mental health that it led to his sudden and untimely death.

Why does it have to be this way? Why are our pasts being erased? Where are the promises of globalisation, of the Canadian dream, where the world is our oyster?

The promises of the Canadian dream don’t belong to first-generation immigrants. Those promises may only belong to their children, or their children’s children. Instead, those newcomers are forced to help relieve the labour shortage, where the greatest job vacancy in Quebec is in the accommodation and food services industry.

There is nothing inherently wrong with working minimum-wage jobs, or occupations considered blue-collar. The crime here is the lack of job and education equivalence afforded to immigrants and refugees; a chance to salvage what little triumphs they have.

The call I received back in my kitchen in Dubai did not come after an afternoon of waiting. It

was the culmination of four years of waiting. I was waiting for a Canadian visa—that untouchable, spectacular, rare-as-a-shooting-star sheet of stamped paper that my people would and have, died for. During that wait, I had to place my life and education on hold, and now, at 26 years old, I am incredibly lucky that my past isn’t extensive enough to be erased.

I’m incredibly lucky that I will graduate from Concordia. I’m incredibly lucky that I have yet to enter the job market and that my first job post-graduation will probably be in Canada.

The same cannot be said for hundreds of thousands of others who are instructed to please humble themselves—and that is a goddamn disgrace.

This article originally appeared in Volume 43, Issue 8, published December 6, 2022.