Barriers to refugees in Montreal: Racism and discrimination in Quebec

Virtual town hall held by The Refugee Centre to platform community concerns

Community organizers rallied at the Concordia-based Refugee Centre’s town hall on March 31 to hear the concerns of the Montreal community and draft their advocacy goals to better support Montreal refugees.

The town hall consisted of community actors from Project Genesis, Revive NCC, South Asian Women’s Centre, United Nations Refugee Agency, and Action LGBTQIA+ avec les Immigrant.e.s et Réfugié.e.s. The livestream was hosted on Facebook and provided automated live transcription.

“The main goal is providing opportunities for guest speakers to be able to speak on that they are working … and to discuss their experience with racism and discrimination and providing suggestions for policy and community action,” explained Lauren Paquay the Outreach Coordinator at TRC.

Health care access barriers

The main concerns raised were the lack of access to health care and systemic discrimination when health care is available.

Ghazala Munawar from the SAWC explained many of the community centre’s members were unable to find therapists due to language barriers and a shortage of therapists in the Quebec system.

“Doctors are asking us [to offer therapy]. We are not trained therapists, we are community workers,” stated Munawar about the lack of available mental health therapists in the health care system.

Safety when navigating the health care system was of particular concern for individuals at the intersection of multiple marginalized identities. Refugees experience marginalization because of their status, but queerness and racialization make navigating the process all the more treacherous.

“Doctors are asking us [to offer therapy]. We are not trained therapists, we are community workers.” — Ghazala Munawar

These safety concerns led to volunteers from AGIR, an organization that supports LGBTQIA+ refugees and immigrants, accompanying a record number of patients to their medical appointments to reassure and assist them.

Iyan from AGIR noted that he was faced with a lot of impatience when he asked for an explanation regarding medical terms for racialized patients. “[The nurse] was looking at us as if we were stupid,” he said on his experience accompanying community members.

Identity and the power to revoke it

The concept of self-identity and the seizure of documents of identification in a refugee’s asylum-seeking process was central to this discussion.

Abdulla Daoud, host and executive director of TRC, notes that in order to be granted asylum refugees must leave behind all forms of identification from their home. “If they come with a passport or a national ID card that’s taken from them by the [Canadian Border Services Agency] and they are given a brown paper which is their only form of identity,” explained Daoud.

The Refugee Protection Claimant Document, also referred to as the brown paper, is what gives a refugee access to health care coverage. Daoud said the main caveat with this document is that it is not accepted across all Canadian clinics and when it is recognized, few health care professionals are aware of its existence.

“There are plenty of days in my life where I don’t feel Quebecois because I’m not meant to feel Quebecois because it’s an identity centered around exclusion.” — Jared Roboz

“The issue is that the health care workers don’t know that they are allowed to provide these services,” attendee Anissa Khan added. “Health care practitioners need additional training on the social, economic and cultural contexts of patients.”

The bureaucratic process involved with processing the brown paper – as opposed to a provincial medical card – leads to overworked health care professionals avoiding to offer certain medical services. When combined with refugees being seen as a societal burden, it leads to additional barriers.

“Refugees are seen as a burden. They’re seen as a charity case,” Daoud stated. He emphasized that it is often forgotten that refugees are forced to leave their homes; many do not foresee their arrivals to Canada.

This othering process resonated with other community actors present.

“I didn’t have the sense of belonging. I didn’t feel like I was African enough because I was born here. I didn’t feel like I was Canadian enough because I wasn’t fully from here according to the standards of Canadian identity,” recounted Sandra Mouafo, the Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion advisor for the Concordia Student Union, “I was waiting for a permission, an invitation to speak on my own behalf.”

“There are plenty of days in my life where I don’t feel Quebecois because I’m not meant to feel Quebecois because it’s an identity centred around exclusion,” added Jared Roboz from Revive NCC.

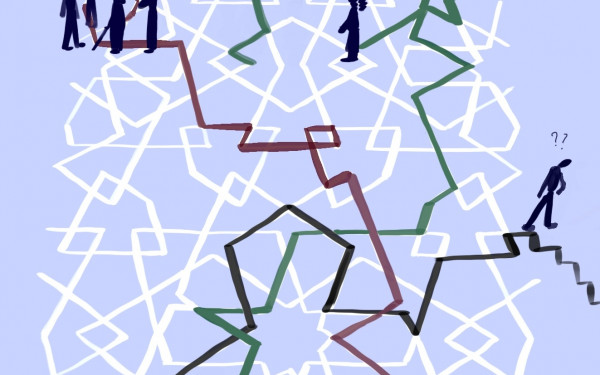

Excessive bureaucracy: Yet another barrier

The cycle of poverty and incessant fatigue that comes with refugee status is only worsened by excessive bureaucratic processes involved with the identity.

“It is unbelievable the amount of paperwork that is necessary for people who are barely able to subsist. The more that becomes difficult, the more you are surveyed, the more you are policed and criminalized. The more bureaucratic it becomes,” stated Anne Favory from Project Genesis.

The bureaucracy necessary to engage in Canadian society often deters refugees from pursuing opportunity.

“We are seeing tons of nurses coming from India who have been selected on the basis of their career and education. When they come here, the process of going back and getting their degrees accepted, getting the evaluation and [reaching] Canadian standards—it’s so difficult,” Munawar added.

For some, their SIN alone can be enough to halt their job search process. The SIN on brown papers always begin with the number nine. Employers can use this pattern to identify refugees and discriminate in the hiring process.

“Canada is the land of opportunity, but what are opportunities if you can’t actually access any of them,” said Mouafo.

_600_375_s_c1.png)